Why Does Da Vinci's Jesus Look So. . . Stoned?

Mike Lankford on the High Renaissance

Let’s not imagine (too vividly) Leonardo sitting back with a bowl of the local cannabis. Such speculations are clearly dangerous—not just to the historical record, but to me personally were I to ever attend a conference of professional historians (roughed up and left in an alley to die most likely). But, nevertheless, if one is attuned to dog whistles, this is a fascinating subject to consider. In the spirit of 4/20, let’s pull the covers back and see what we find.

The creative explosion that occurred in northern Italy during the 30-year period we call the “High Renaissance” remains a mystery to us still, despite the centuries of interpretation that have followed it like an echo. There was a spirit loose on the ground, something new and fascinating that had stirred people out of their long sleep—but our ability to account for it now, based on the scanty evidence we have, would seem nearly impossible. From a distance, this awakening looks a bit like a miracle, but of course it was nothing of the kind. These were human beings, a lot like us (not entirely, of course, but mostly), and what woke these human beings up and filled them with art is a question that fascinates us to this day.

What we do know of the time is that the expansion of trade and the invention of printing led to a greater sense of the broader world, and of different cultures—and that this increased awareness of others, combined with an interiority created by reading, this contrast somehow led to the emergence of the modern, self-aware individual. The modern artist who saw himself in others.

And this apparently first happened in northern Italy, mostly around Florence. Why, it’s hard to say.

The problem plaguing historians who attempt to explain this creative explosion is that it occurred amongst a mostly illiterate population that didn’t keep diaries or write letters about the intense weird guy living upstairs. The difficulties created by this lack of written evidence has forced otherwise straight-laced, respectable academics to speculate—and the result has been the mythology of the great artist. The tale of a superman who talks to God. A story at bottom about art coming out of magic and muses. A story that obscures more than it illuminates.

“I can say from experience I’ve seen jazz musicians with that look on their face, but never a painting of Jesus.”

So what was it, the local water? Probably not. Anyone drinking out of the Arno would be dead in a week. What caused it, we don’t know, but what can be said with certainty is that two of the greatest individual artists in western culture both emerged from that explosion: Michelangelo Buonarroti and Leonardo da Vinci.

Two more different artists could not be imagined though. In the year 1512 for instance, both men were at the peaks of their careers—but you wouldn’t know it by looking at them. Michelangelo had just finished a four-and-a-half-year struggle to paint the pope’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel in Rome and the effort had taken a huge toll.

Depressed and somewhat frantic, the 37-year-old “divine” Michelangelo was a wreck. He had just spent those four-and-a-half years painting with his arms lifted high over his head, and as a consequence suffered from scoliosis, arthritis, a goiter, and an eye infection from the paint dripping onto his face—not to mention the consequences of once stepping backward off the scaffold and falling 60 feet to the marble floor. The man was lucky to be alive, but did he take a break and rest up? No. What he wanted to do was get back to sculpting marble so he could wave a heavy hammer in the air all day. The man was a machine. He was also a poet and a serious intellectual, but the drive in him more resembled a divine fury rather than a divine grace. Michelangelo stayed pissed off and his art somehow came out of that.

Leonardo by contrast seemed to be sitting in a garden up in Milan studying various things like anatomy, water turbulence, fossils and seashells, whatever passed before his eyes became a fascination, for a while at least, but he kept returning obsessively to his 21-by-30-inch Lisa—not quite sure about some background detail yet, still tweaking the smile. While Michelangelo painted by the square foot, Leonardo painted slowly by inches. Consequently, the more time he spent with the subject, the more focused and complex it became to him. The Mona Lisa was for Leonardo a philosophical painting, one which provoked thought and consideration, one in which he saw himself. The painting had evolved through stages and looked very different now from the painting he started in Florence. He’s following his own imagination, allowing the painting to evolve. He’s looking for a kind of truth. This is not job work.

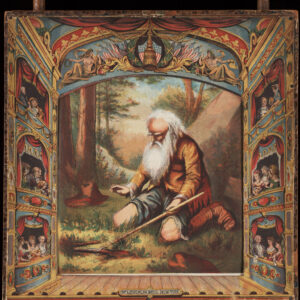

Salvator Mundi, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1500

Salvator Mundi, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1500

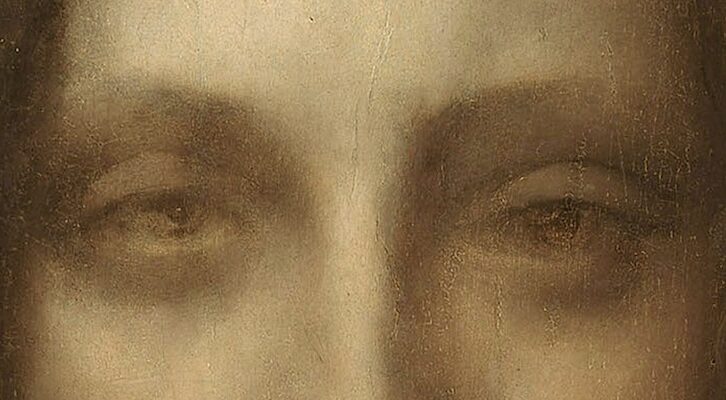

It was also during this period that he devoted himself to works which required more planning, such as St. John the Baptist, and the Salvator Mundi, which was only recently rediscovered and properly identified in 2012, buried under a very bad over-painting once described as making Jesus look like “a drug crazed hippy.” As many others have remarked of the cleaned painting as well once it was on display: Jesus does look rather stoned. “Red eye” doesn’t start to describe him. A plebeian response perhaps, but his eyes are red and he does look rather ‘transported’ shall we say.

It’s Leonardo’s depletion of a spiritual being in the midst of a total connection, the eyes of an inward-looking mystical visionary caught in the moment. Almost as if Jesus is channeling Yahweh right in front of you.

The real question though is, in his own experience, what is he basing this on? Is this a look Leonardo saw in others and copied? Did it remind him of something else? Where did he find it? Was it not his belief that in portraiture the actions of the mind be manifest on the outside, that we see the person think? What does divine revelation look like when seen close up in the eyes? What is Jesus thinking?

I can say from experience I’ve seen jazz musicians with that look on their face, but never a painting of Jesus.

Even though Vasari listed herbs and their properties as one of Leonardo’s areas of interest, this is one of those subjects that has been taboo around Renaissance studies. But the use of herbs for artistic and philosophical purposes was old when the ancient Greeks discovered it 2,000 years before. In a rule-breaking and innovative time such as the Florentine Renaissance, inhaling a little cannabis might’ve helped with the night’s entertainment, especially if you played the lira and improvised a lot—as Leonardo did. We know the weed was around. If he didn’t smoke it, he sure smelled it. After all, in 1484 Pope Innocent VIII had banned the practice of smoking cannabis as sacrament during mass—so ask yourself, how bad did the practice have to get before the Pope himself had to step in and stop it? Perhaps the reason the subject remains untouched by historians is because Leonardo Studies arose with Italian Renaissance Studies in Victorian England, where some subjects were allowed but certain others weren’t. Homosexuality was one. Cannabis another?

Barbara Reynolds in her biography of Dante points out how ordinary it really was: “Knowledge of herbs and medicinal potions was passed from country people and herb-gatherers to apothecaries, and herb gardens were a common feature of monasteries. From the early 14th-century manuscript Tractatus de Herbis it is evident that the plant Canapa (Cannabis sativa) was known and available.”

So what do we make of this? To my mind, the High Renaissance is akin to other creative explosions we do know much more about, like London and the birth of the novel, or New Orleans and the birth of jazz, or Paris and modern art, or New York and modern jazz—all these places had an illicit, dangerous edge to them. Borders were being crossed, laws bent, hybrids being born, and, yes. . . herbs were probably smoked.

They had cannabis back in Jesus’s time as well, but that’s another subject.

Mike Lankford

Mike Lankford's Becoming Leonardo was selected by the Wall Street Journal as a 2017 Book of the Year. He is also the author of Life in Double Time: Confessions of an American Drummer, selected best music book of the year by eight major newspapers including the Chicago Tribune. He lives in Bend, Oregon.