Why Do Writers Keep Multiple Copies of Books Around?

Melissa Febos, Carmen Maria Machado, and More on Their Beloved Editions

I own multiple copies of books—Stoner, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Catcher in the Rye. There are personal reasons I will cherish each of them for the rest of my life.

One friend called the books she has in multiples “a little family of weirdos who all sit on the shelves together.” Another keeps out-of-print multiples and updated copies of the same books. Many people buy multiples because they travel and want to have copies on the road; others buy multiples of books they adore because they intend to give them away, although they often end up holding on to them for reasons they don’t understand. Certain books are collectibles. Different translations of the same books, signed editions, and several artful covers are reasons to double and quadruple up.

But probably my favorite explanation for multiples comes from a man who “rescued” a hardcover of a book he already owned from a pool hall to rectify the “great injustice that such a good book was just sitting there in a billiard parlor having been bought by the yard with hundreds of other books as wall decor.”

In my fascination for the topic, I wondered what books are kept in multiples by writers, and so I asked a few.

Amy Bloom, author, most recently, of White Houses (Random House, 2018).

I keep multiple copies of: Pride and Prejudice (Austen), Jane Eyre (Bronte), The Stone Diaries (Shields), The Deptford Trilogy (Davies), The Habit of Loving (Lessing), A Bargain for Frances (Hobson), Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak), and Kindred (Butler).

I love all of these books and they have all brightened my life as a reader and taught me something (more than one thing) as a writer. I feel a great obligation to share them with other people, who have only evinced the slightest interest in reading or writing.

Francine Prose, author most recently of Mister Monkey (Harper, 2016). A book of essays, What to Read and Why, will be published by Harper this summer.

I have eight rooms of books in my house, and though they’re fairly well organized (fiction alphabetized in one place, biography in another) I tend to lose track, so some of my duplicates are purely accidental: I can’t find a copy and order another, and then find the first copy, and can’t bear to give either of them away. This is partly because, rather than admit my mistake, I’ve convinced myself I can’t live without both copies. In this way I have accumulated (among others) two copies of Jonathan Cott’s biography of Lafcadio Hearn and several copies of The Confessions of Saint Augustine.

The multiples are more complex, and more purposeful, if not more sensible. In fact the whole process is probably less sensible. Most of these books come from book sales at our local libraries. I’ll see a favorite book and feel the need to rescue it from the table on which no one seems to be giving it sufficient love and attention. How could someone just leave my old friend there?

In this way, I’ve acquired four copies (all different) of Lampedusa’s The Leopard, three copies of Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees. I’m not precisely sure why I have more copies of Henry Green’s novels than anyone else’s. Perhaps because something about them seems fragile—I’m afraid they’ll disappear if I don’t keep close watch over them. I have about a half dozen copies of Green’s novel Concluding; the number grew lately when New Directions reissued the previously out-of-print novel. I have several copies of Rachel Ingalls’s Mrs. Caliban, acquired the same way. I have probably a half dozen copies of Jane Bowles’s Two Serious Ladies, because that book has been reissued several times, and because a beloved class once gave me, as a going away present, a first edition of The Collected Works of Jane Bowles.

I have countless books in three editions—galleys, hardcover, and paperback—Bolano’s 2666 is among these—because they all seem to me like different books. And I don’t know why I seem to have six copies of Great Expectations, except because I love that novel so much. I have the complete stories of Chekov (Garnett translation) in two editions of many volumes each; I like the covers on one better than on the other. And books in different translations don’t even seem, to me, like the same book at all. I have numerous translations of many classic novels.

Finally, like many writers, I guess, I have boxes and boxes of books I’ve written or to which I’ve contributed. I’m not sure what else to do with them. I’ve heard it suggested that writers shouldn’t keep more copies of a book in translation than it sold in the language into which it was translated, but I haven’t been able to follow that wise advice. What am I supposed to do with those books—throw them out? Feed them to the squirrels in the barn? I just gave a copy of one of my books—in Korean—to a friend who reads Korean, and it felt great, seeing that lovely empty spot on the crowded shelves.

Is this hoarding? I don’t know. I watched the TV show Hoarders only once, and had to stop in the middle, because it seemed so frightening—in an uncomfortably personal way.

Melissa Febos is the author of Whip Smart (St. Martin’s Press, 2010) and Abandon Me (Bloomsbury, 2017)

I keep multiple copies of my favorite self-help books, in the (relatively common) event that one of my friends is interested in helping themselves along similar lines. I’ve probably purchased ten copies of Tara Brach’s Radical Acceptance and at least twenty of Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart, which I always keep doubles or triples of on hand because I gift it so often, since things fall apart so often.

Space in NYC is so limited and I have so many books that it’s hard to justify doubles (I’m paying exorbitant rent for every one of those books), so they don’t abound in my permanent collection. But there are a few I’ve had over the years, usually because the battered childhood copy is too fragile to use, but I can’t let it go: The Chronicles of Narnia, Franny and Zooey, some poetry collections. And I’ve needed a beloved volume sometimes so desperately that I’ve purchased a second copy even when I knew I had one somewhere, or had lent to it a friend: The Lover, Written on the Body, Autobiography of Red.

John Sayles’s most recent novel is A Moment in the Sun (McSweeney’s, 2011).

I only have doubles of two books that I can think of, and in both cases it’s because one copy is in English and one in Spanish, which I still like to brush up on. They are the long Faulkner short story The Bear (El Oso), and Cien Años de Soledad (A Hundred Years of Solitude). Both books worth reading again every five or six years.

Elizabeth Strout’s New York Times bestseller Anything Is Possible will be released in trade paperback on March 27.

The book I have the most copies of (I have six copies of this book) is The Collected Stories of William Trevor. This is not a small book. It’s what they used to call a door-stopper, I think. But I have two copies in the bedroom and one on the piano and one in the living room on a book shelf. And in Maine I have one in the bedroom and one on that piano as well.

I really don’t know why I have so many copies of this book, other than I love his work, and turn to it frequently, and apparently at some point thought I needed another copy to have close by, and so I bought another and another and another. . . I know I have given it as gifts, but I still have all these copies. (I just noticed I also have his Selected Stories in hardback—it was sticking out from under the bed.) Interesting. But his Collected Stories are the best because they include more than the Selected Stories—maybe that’s why Selected Stories was half under the bed. At any rate, his stories have meant so much to me over the years, and I very frequently thumb through them looking for one I remember, and then I will read others that I have forgotten—and so forth.

Rajesh Parameswaran is the author of I Am an Executioner: Love Stories (Knopf, 2012).

I’m slowly collecting Moby-Dicks. I buy a different edition each time I read it. So far, I have three. I have a couple of different Adas, Lolitas, Don Quixotes, and Amerikas, and some Bishops, Dickinsons, RK Narayans, MFK Fishers. It’s the aesthetic pleasure of handling different editions of a book you adore, like seeing your beloved in different clothes.

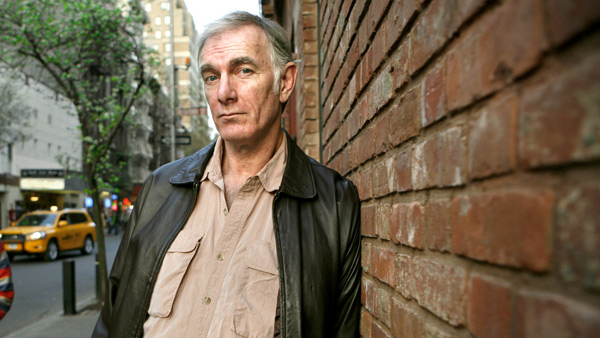

Ron Rash is the author of Serena and many other books.

I have two copies of many books (often a hardback and paperback), but there are a small number of books I have at least three copies of so that they are close by. These are the books that I often pick up in random moments, for pleasure, for edification, for the sheer wonder that a human being could have written something so brilliant. Among these are Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom, Flannery O’Connor’s collected stories, Jean Giono’s Song of the World, and, most importantly, William Shakespeare’s plays.

Madeleine Thien is the author of Do Not Say We Have Nothing (W. W. Norton, 2016) and Dogs at the Perimeter (W. W. Norton, 2017).

I keep multiples of Hannah Arendt’s Men in Dark Times and Between Past and Future, Ma Jian’s Red Dust, Alice Munro’s Open Secrets, James Baldwin’s Collected Essays, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, and Cees Nooteboom’s All Souls’ Day.

I’ve lived a nomadic and restless life, and my books are either gone, in storage, or in other people’s apartments. These books I mention have steadied me for decades; I’ve picked them up in bookshops around the world. I turn to them in conversation, as I would to friends and mentors, when my heart is broken, when I’m in wonder at language and possibility, or when I’m trying to see something that is eluding me. I find these writers generous and visionary. There are two books I relied on, fifteen years apart, that I turned to when first my mother and then my father were dying: the Cees Nooteboom I mentioned above, and Robert Macfarlane’s The Wild Places (I only own one copy and carry it with me). It’s strange to think that a book can shelter you, or care for you, but that’s what I felt.

Amanda Filipacchi is the author of four novels, most recently The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty (W. W. Norton, 2015).

Working Days: The Journals of the Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck is a remarkable account of a writer’s determination to stick to his writing schedule despite life’s inevitable discomforts, distractions, and challenges. In these daily reports, Steinbeck captures the inconveniences he struggles with, from the pounding of his neighbors as they lay new floors, to his pen slipping through his sweaty fingers due to the hot weather, to his wife’s illness. The book is full of inspiring realizations, such as, “The failure of will even for one day has a devastating effect on the whole, far more important than just the loss of time and wordage.” I have several copies of this book and love giving it to friends. Many of my friends are writers and they often struggle with discipline. Hopefully this book motivates them—or at least reminds them that, even when life gets very difficult, you can still find the will to stick to your schedule.

Carmen Maria Machado is the author of Her Body and Other Parties (Graywolf, 2017).

I have Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and all of Kelly Link’s collections. For the same reason—to give them to people who need them.

Steven Almond’s Bad Stories: What the Hell Just Happened to Our Country? will be published in April 2018.

I have four copies of the novel Stoner by John Williams stashed around my house. I don’t mean that I have my own copy and three extras that I keep as standby gifts. Although I’ve given Stoner away to plenty of folks, mostly other writers. No. All four copies belong to me, all four are marked up to some degree, and all four are different editions. No one who knows me will be at all surprised by this.

I should add that I’m not a book fetishist. Stoner is the only book I own in multiples. I have lots of copies because I love it so much, and because it nearly went out of print, and because I spend an inordinate amount of my waking life picking Stoner up and reading a page or two (or ten), simply to remind myself that language can be so simple and beautiful and true. I imagine my mother-in-law feels the same way about the crucifixes she keeps in every room. Just seeing the artifact brings the story alive.

Love is a human act of becoming. That’s what Stoner says. And I want to be reminded of that as often as possible.

Xhenet Aliu is the author of the novel Brass (Random House, 2018) and Domesticated Wild Things and Other Stories (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

James Baldwin famously wrote, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” I keep multiple copies of Jennine Capó Crucet’s Make Your Home Among Strangers, a novel about a first-generation American and first-generation college student confronting all the things she didn’t know she didn’t know, because I’m an academic librarian at a small college that serves a lot of students who recognize themselves in Lizet, the book’s heroine. I’m generally not a fan of recommending books that simply mirror and/or reinforce one’s own life experiences, but I think this book is particularly useful for these readers because it acknowledges their struggles while looking back on them from the other side, and it does it without being obnoxiously instructive or pedantic. Plus, it manages to be important while also being funny and entertaining, which is particularly important when trying to convince students without a whole lot of free time that they should open up a slot in their schedule for leisure reading.

Heather Lloyd’s debut novel is My Name Is Venus Black (Dial Press, February 2018).

Not long ago, I lived in a house in Colorado with loads of bookshelves. I owned multiple copies of favorite titles, but it was hard to keep a steady supply, since I practically forced them on people I loved—or at times, on anyone who could read. Recently I moved to New York City where I live in a tiny apartment with little space for books—so alas, no duplicates. But here’s a few titles I’d give away even if they were my only copy:

A New Earth by Eckhart Tolle. I’ve gifted at least ten of these, mainly because I think this book should be required reading for human beings. I’ve long been a fan of spiritual self-help, but this one didn’t just teach me something, it changed me in ways that have lasted. To this day, when I’m angry, overwrought, or stuck in a self-centered warp, a quick dip into its pages can reset my thinking and my way of being in the world.

Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp. Hands down my favorite memoir of all time—and not just because I’m in recovery. Her story reads like a plot in a novel, her voice speaks straight to your face, and her honesty stings in that good way that means someone is telling the truth—not just about herself, but about you.

A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry. This novel is the haunting kind, where years later you can’t recall details, but you can never forget the way it held you in thrall and moved you as you read. I loved how it immersed me in a foreign world—even one rife with poverty and injustice. And yes, these characters suffer plenty, but never without dignity and courage. After I closed the cover, I felt equal parts sad and relieved. Like I’d just had a really great tantrum and now I could finally breathe.

Esmé Weijun Wang is the author of The Border of Paradise and the forthcoming The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays (Graywolf Press, 2019).

I keep multiple copies of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard. It was a book that influenced me in my earlier writing years, and for a time I would buy a “new” edition at used bookstores whenever I came across them—there are surprisingly many of them. Funnily enough, I rarely consult the book now, but I still think it is a beautiful example of a particular kind of nonfiction, and I very recently gifted the newest edition to my sister-in-law.

Why did I buy multiple copies? Honestly, I’m not sure. It was a compulsion of sorts. I was intrigued by all of the different covers available for this book, and I also enjoyed the feeling of accumulating editions of a book that had such a deep influence on my literary nonfiction writing. Some covers are lovelier than others, but for a while, I wanted to own as many of them as possible.

Betsy Robinson

Betsy Robinson’s novel The Last Will & Testament of Zelda McFigg is winner of Black Lawrence Press’s 2013 Big Moose Prize and was published in September 2014. This was followed by the February 2015 publication of her edit of her late mother, Edna Robinson’s, novel, The Trouble with the Truth, by Simon & Schuster/Infinite Words. Betsy is an editor/fiction writer/journalist/playwright.