Why Do We Love Reading About Cheaters and Schemers?

Art Forgery, Faked Deaths, and More: A Reading List

If one of the pleasures of fiction is vicarious experience, then it is perhaps logical that readers should be drawn to books about breaking the rules. Confronted with any prohibition in day to day life, it is the most natural response to imagine acting against it. Who has not seen a “Do not walk on the grass sign,” and envisioned themselves stepping onto the lawn behind? Is there anyone in the world who can watch a security van deliver cash to a bank without briefly considering how they might pull off a heist?

Most people, however, have something that stops them—Training? Social conditioning? The realization that new life you would make with a purloined box of banknotes might not actually be that fun?—there is a switch which trips within them and they walk on, past the lawn, past the bank. Maybe, however, they are still thinking “what if . . .”

Which is where literature comes in. Part of the allure of books about breaking the rules is the chance to continue that little thought experiment longer than one usually might. What really would happen if I tried to cheat? Or if someone cheated me?

There are certain recurring patterns in literature on this subject. Sometimes cheats succeed. More usually they fail. Occasionally rule breaking goes unpunished. More often there is a reckoning. What most narratives seem to agree upon, however, is the thrill of transgressing a prohibition. Scheming is addictive and tends to beget more scheming. The greatest pleasure I had in plotting my own book, We Begin our Ascent, was laying out the way my narrator, a professional cyclist, decided to use banned drugs, and the way this first transgression necessitated and justified further ones. People are good at normalizing their own actions, at adjusting to rationalize even their most extreme acts. In this sense, rule-breaking seems utterly invigorating, natively literary: with each successful deceit the world is reframed, becoming seen anew, filled with possibility.

Charles Portis, The Masters of Atlantis

Charles Portis has a knack for writing conmen, and The Masters of Atlantis contains one of his best. Lamar Jimmerson’s ailing religion of Gnomonism is infiltrated by a chancer, Austin Popper, who, among other things, commissions Jimmerson a highly inaccurate biography, titled Hoosier Wizard, and flees into the Rocky Mountains on a quest to manufacture gold.

Nell Zink, Mislaid

The central deception in this novel is switch of identity. Peggy, escaping from her disastrous marriage along with her daughter Mireille, takes their new names and birthdates from gravestones. That taking these new identities should also entail changing race intensifies the sharpness of the satire at work here. The book sends up Southern preoccupations about race and the unspoken desire of those in power that people of color conform to white patterns of behavior.

William Gaddis, The Recognitions

What could seem more glamorous scam than art forgery? Yet in Gaddis’s massive novel the production of fake masterpieces is spiritually corrosive. The struggling painter Wyatt Gwyon recreates Dutch masters for a patron, unravelling in the process. The novel is at times portentous, mean-spirited and a little too aware of its own quality. But it is also very good. It features the funniest (probably only) chapter about a stolen amputated leg in literary history.

Steve Tolz, A Fraction of the Whole

Australia is a nation with a fondness for schemes and subversion, and scammers are well-represented the country’s literature. Peter Carey’s Illywacker could easily appear on this list, but instead I’ve picked Steve Tolz’s hilarious debut novel. Over the course of the book Jasper Dean struggles to untangle himself from the scams of friends and family, including his father’s idea for a lottery everyone in Australia takes it in turn to win, and his uncle’s faking his own death.

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

Am I suggesting that the creation of the Anglican church was, well, a scam or a cheat? Maybe. If so, however, it is not out of theological conviction but from a desire to include this novel in my list. Thomas Cromwell, as envisaged by Mantel, is a master of maneuvering and plotting. He does everything he can to get on the right side of an unstable king, and then having done so rearranges the spiritual life of his nation to give the king what he wants. Sometimes the best way to get around the rules is to re-write them.

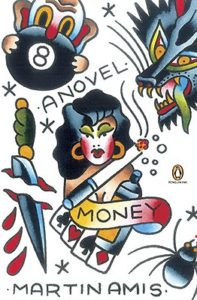

Martin Amis, Money

If the 80s were the prime years of the synthetic and artificial, then this novel takes these characteristics to their logical extents. Money is a novel with precious little money in it. Rather the book is filled with the possibility of money. John Self chases between London and New York in search of his big payday, spending against the anticipation of it all the while. Maybe the scam on which the novel turns it too cute and literary, but it is pleasure to witness a grand deception from the perspective of the victim, to get the visceral sense of what it is like to have been played in such a way.

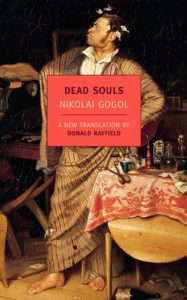

Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls

This novel is the original epic of cheating and deception. Chichikov is a man of appetites, both immediately familiar and strangely enigmatic. He travels around the crumbling estates of rural Russia buying “dead souls”: that is, peasants listed on estate-keepers rolls who have died since the last census was taken. The scheme is ultimately revealed as a way to accumulate a theoretical holding of serfs against which Chichikov can acquire a loan, yet the intricacies of this plan are less important than the interactions that allow its fulfilment. Chichikov meets a luminous, often hilarious, array of characters. As with any great conman, he facilitates the projection of those he meets, drawing out delusions, frustrations and thwarted aspirations.