Why Didn’t I Want My Beloved Father to Read My Memoir?

Martha Hodes on Diving Deep into the Trauma of Her Hijacking

On a Monday evening in March, my publisher delivered the final-pass page proofs of my memoir, requesting my approval within two days. On Tuesday, I stopped by my father’s apartment, as I often did early in the week. I always brought him the Sunday New York Times, and that day I also carried with me the bottle of drain cleaner he’d requested and a box of chocolate chip cookies. This time, though, I found my father, 98 years old, slumped over on the bedroom floor. I thought he was dead, but the EMT’s roused him and an ambulance took him to the hospital. The next morning I returned the last corrections to the page proofs, and my father died that afternoon.

On September 6, 1970, when I was twelve years old, my thirteen-year-old sister and I were flying, unaccompanied, from Tel Aviv to New York, when our flight was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Ours was one of five planes hijacked that day, three of which ended up in the Jordan desert. My sister and I were among those held hostage for a week. We didn’t talk much about the hijacking when we got home. Like other adults at the time, my father believed that rehashing a traumatic experience could only stop us from getting on with our lives. “You were home!” he told me, thinking back. “Nothing else really mattered.” Those words nicely summed up how I had treated the experience too.

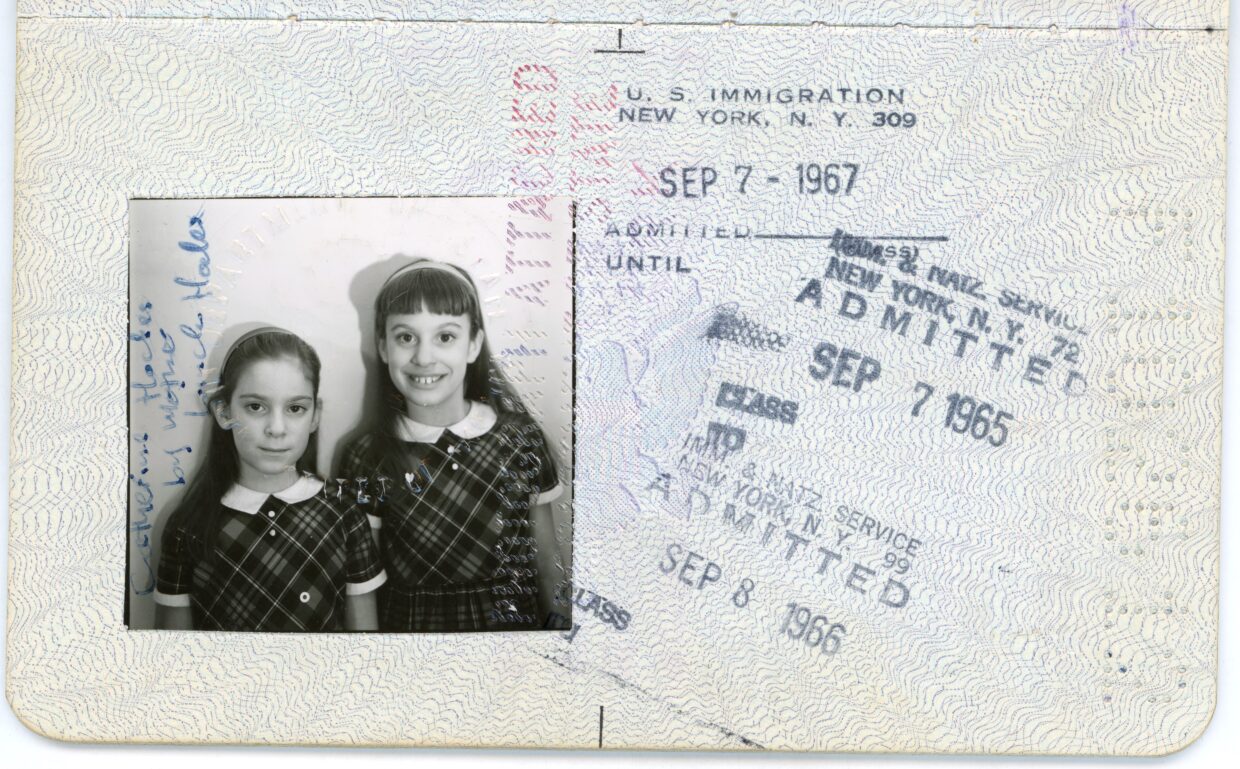

Our shared passport for our earliest trips to Israel. We never retrieved the passport confiscated by the Popular Front commandos.

Our shared passport for our earliest trips to Israel. We never retrieved the passport confiscated by the Popular Front commandos.

Fifty years after I came home from the desert, I set out to write about the hijacking, bringing my skills as a professional historian to the task. I sifted through airline archives, combed through State Department telegrams, and read transcripts of telephone calls between President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger. I studied interviews given by fellow hostages, pored over newspaper coverage, and watched the nightly television newscasts. I absorbed the political literature of my captors and watched raw footage of the press conferences they held while my sister and I sat inside the plane, unsure of our fate. I went back to the Jordan desert.

My father told me often that he hoped to live long enough to read my memoir. While I was researching, he let me rummage through his disorganized filing cabinets, and one day I found an issue of a Boston newspaper with an interview my sister and I had given less than a week after our return. I also rifled through my father’s self-storage unit, where I found a slim manila folder labeled “Hijack.”

Inside I found various mementos: a slip of paper with the three telephone numbers he had dialed each day we were gone (the airline, the State Department, the Red Cross), and a New York Times clipping headlined “Released Hostages Tell of Their Ordeal in Desert,” along with the Times “Quotation of the Day,” in which my sister told a reporter, “Now I am going to thank God and have a bath.” I saw that my father had saved no earlier news reports, the ones with headlines like “5 Nations Reject Terms for Freeing Hostages” and “Hijackers Set ‘Final’ Deadline.” I understood that he had curated the folder’s contents to back up his insistence that, as he told me decades later, “I always knew you were coming back.” My stepmother told me a different story, though, recalling my father as “a man on another planet.” She added, “Was he thinking of never getting you back? Well, yes. Killed and never coming back? Oh, yes.”

After my father died that March afternoon, I needed to reckon with his apartment, the cramped rental in midtown Manhattan where I’d grown up and where he’d lived for sixty-six years. Mountains of unsorted papers were heaped on shelves, on the floor, behind furniture. Folders labeled “Family Letters” held electric bills, and folders labeled “Taxes” held letters from his mother.

The man never met a parking ticket or a printer test-page he didn’t cherish. In one plastic bin, apparently saved for the subscription cards he liked to tear out of magazines, interleaved with ripped-open envelopes emptied of mail, I was astounded to find a letter that the airline president had written to my father after my sister and I returned from the hijacking. I was sorry I’d not found it earlier, but fellow hostages had shared with me their own versions of that document. Elsewhere I found a letter from displeased passengers chiding my father for declining to join a lawsuit against the airline; I’d already found his initial refusal, so this too told me nothing new.

The postcard that Catherine and I wrote to our father and stepmother. It would arrive in the mail weeks after we returned.

The postcard that Catherine and I wrote to our father and stepmother. It would arrive in the mail weeks after we returned.

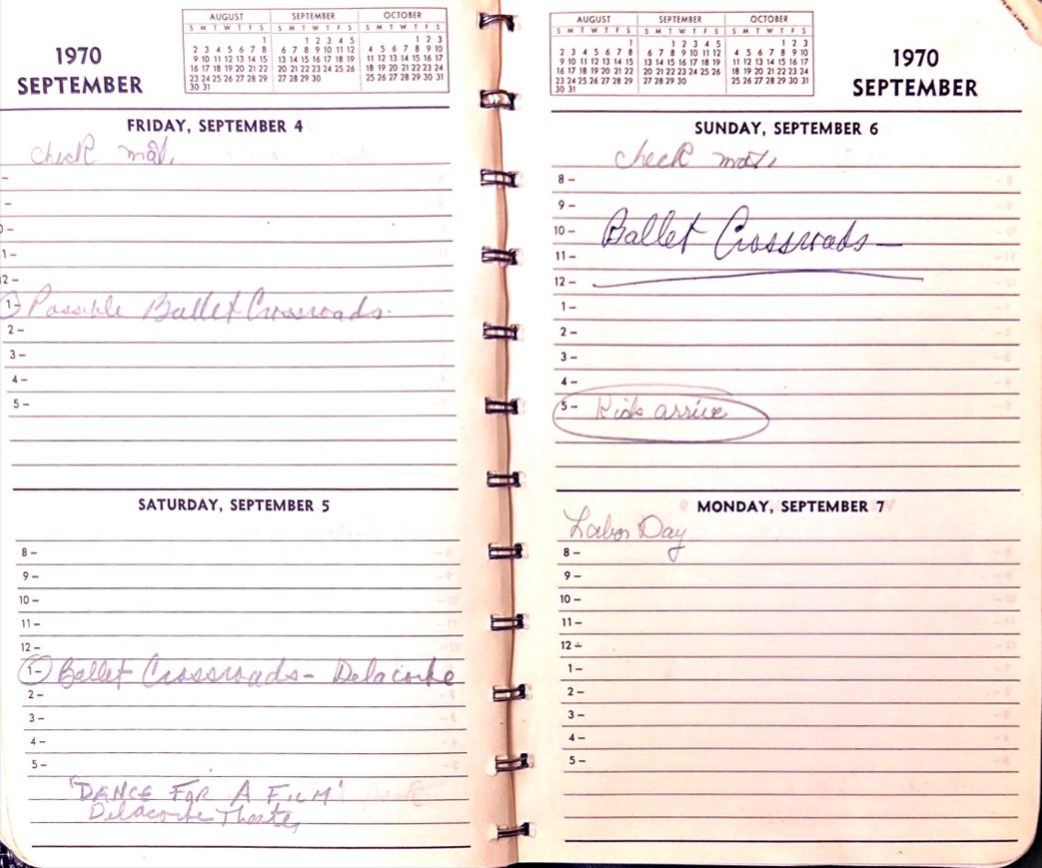

But there was one document I unearthed that I wished I’d been able to include in the memoir. My father’s 1970 appointment book was spiral bound with a cheap green plastic cover. That summer had been a busy one for him. In the 1940s and 50s he was a principal dancer with the Martha Graham company, and in 1970, in his mid-forties, he was running his own small troupe. The appointment book’s pages were filled with the names of dancers and choreographers: “Twyla Tharp at Council,” “See Agnes DeMille sometime today,” or simply, “Graham.” He reminded himself to “go to NYC ballet” or get “Tix for Ballet Theater.” There were notations for conferences, consultations, and travels (“Dance Panel,” “League of NY Theatres,” “Perf Arts Staff Meeting,” “Try arrange trip Ballet Center of Buffalo”). His company would be performing in the New York Dance Festival in Central Park in early September, set to open on the day my sister and I were to arrive home, and August’s pages were filled with reminders for rehearsals, run-throughs, and visits to the park’s outdoor theater.

If you were writing a biography of Stuart Hodes and you didn’t know his daughters had been held hostage on a hijacked plane, his own daily record would not tell you otherwise.

For Sunday, September 6, my father had written “Ballet Crossroads,” the name of his company’s program of dances; in my stepmother’s handwriting, next to the slot for 5pm, were the words “kids arrive.” My father wrote nothing else on September 6, the day our plane was hijacked, and nothing on September 7 either. Turning the pages, I found September 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 blank too. My sister and I came home on September 14, touching down at Kennedy Airport at 8:30pm. I knew from family conversations that my father and stepmother had arrived at the terminal hours early, and I knew that when my sister and I saw my father, and he saw us, we all broke into a run until we were safe in an embrace.

But September 14 lay blank too, and so did the next day, and the next. Just as my father had curated the contents of the folder he labeled “Hijack,” so too had he curated his appointment book entries. I knew from my stepmother that my father wondered if my sister and I might die, but from the moment he saw us running toward him, he could believe that he’d never doubted our return. There would be no record that we hadn’t come back on the day my stepmother jotted down “kids arrive,” and by recording nothing after that, not even our return eight days later, the entire ordeal could vanish. If you were writing a biography of Stuart Hodes and you didn’t know his daughters had been held hostage on a hijacked plane, his own daily record would not tell you otherwise.

As it turned out, the rest of the month of September was blank too, and so were October and November. My father didn’t note the Boston newspaper interview or the two visits we hosted from fellow hostages. My own diary tells me that my father took me to school soon after I got home, that we all visited my stepmother’s family in New Jersey one weekend and my father’s family in Mount Kisco another, that my father took us to a Broadway musical, and that he and my stepmother celebrated their fifth wedding anniversary. My father resumed writing in his appointment book in December: “Joffrey II.” “Arts Council.” “Pick up videotape.” Why hadn’t he written a word for months after we came home?

My father’s diary.

My father’s diary.

Whenever I asked my father what the hijacking was like for him, he would tell and re-tell a few well-crafted anecdotes: that he’d gone on with the show in Central Park, that when we ran into his arms at the airport, my sister had exclaimed, “Oh, Dad, we were so worried about you!”—words that delighted him, since it meant we hadn’t suffered so much during the week in which newscasters nightly announced our potential death. My stepmother remembered my father, during our week in the desert, as devastated, shut down, frozen. My father told me that once we came home, nothing else mattered, but was he shut down and frozen for months afterward? I couldn’t press my stepmother on this point because by now she was suffering from severe dementia, and I couldn’t press my father because he was gone.

When my sister and I returned from the hijacking, I chose to emphasize the more light-hearted aspects: that our captors jumped rope with the children, that we hostages laughed as we sang that year’s hit single “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” changing the lyrics to living on a jet plane. Writing the memoir, though, I’d delved deeper, much deeper. My father would never get to read that version, the one in which my sister and I wondered if we would ever get home, the one that reckoned with weapons and dynamite and deadlines, fear and trauma.

The day after my father died, I completed the one remaining task for my book, confirming the jacket copy; my memoir would go to the printer the next day. Of course I could have given my father the manuscript any time, but I never did, and his 1970 appointment book helped me understand why. I didn’t want to disrupt the soothing story of the hijacking that he’d always told himself. I’ll never know how he would have reacted to a more complex, more disturbing narrative, but I’d done the work of writing the memoir for myself, not for my father. For me, his death came just in time, for he would never have to suffer through reading it. Or, more accurately, I would never have to suffer through my father reading my memoir.

_____________________________

My Hijacking: A Personal History of Forgetting and Remembering by Martha Hodes is available now via Harper.

Martha Hodes

Martha Hodes is professor of history at New York University. She has presented her scholarship around the world, and serves as a consultant for documentaries, television and radio, and museum exhibitions. She is the author of the award-winning books Mourning Lincoln; The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth Century; and White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the Nineteenth-Century South. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation, and the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. My Hijacking: A Personal History of Forgetting and Remembering is her latest book.