Existential ambitions are formulated in such extreme and simple language that they appear like human universals, immune to situation, history and material conditions. But they never arise in a cultural vacuum. Today the question why do this? is included in nearly every mountaineering narrative. Another popular recent climbing film, The Dawn Wall (2017), about Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s climb of the notoriously unclimbable Dawn Wall of El Cap, opens with the two men sitting in their portal edge and receiving a call from a NYT reporter. The reporter has two questions for them: “how are you?” and “why are you doing this?”

Rather than the climbers providing answers, it’s actually the HD footage in today’s climbing films that alone provides the kind of answers the public seems to accept. Perhaps the best example of this is Base (2017), a fictional story about BASE jumpers starring celebrity BASE jumper Alexander Polli, who died in a jumping accident before the film’s release. The story tracks his character, JC, through two jumping partnerships in which his partners both die, one after the other. Notably, the question why? does not figure much in this film, but this is because the GoPro footage—firmly built into BASE jumping culture—answers it a priori. This is especially heightened for the latest and most deadly variation of the sport, namely wingsuit BASE jumping, in which a sort of flying-squirrel-suit-like onesie allows the jumper to glide for long enough to simulate flight. Most of these GoPro videos are taken on jumps in spectacular wilderness locations, so that the human appears to be dipping low like a starling, playfully skimming the wild terrain.

One video and you get it: because it’s that cool.

While why? doesn’t feature as strongly in Base as it does in other contemporary films, what does feature strongly is JC insistently asking his soon-to-be-dead partner, “Do you really want this? Do you want it? Do you?” He assures his partner that if indeed he really, really wants it, he’ll be able to do it. The authenticity of the desire is key to the physical ability—in order to do it, you have to really want it—so that the act and the desire ultimately become synonymous, as if desire itself were a kind of human flight.

Poster for Base.

Poster for Base.

Meanwhile, at the same time, the accomplished climber has come to stand for the apex of not only physical but professional, financial and social achievement—the winner standing on top of the world. So much corporate advertising signals that life, or at least what counts as “having a life,” is indistinguishable from “upward mobility,” but not only in the economic sense, not anymore. The image of climbing-as-success works to naturalize the relentless drive for more, as if amassing wealth were the most natural, obvious, spiritually and environmentally integrated thing to do. As if it were freedom itself.

The climber is the ideal figure of this, and not only as metaphor. A 2018 article with the provocative title “The Equation that Will Make You Better at Everything” argues that excellence in any domain requires the same stuff. It uses the image of the rock climber, as well as a certain narrative about the climber mindset, to help you to “grow your career,” “grow your team and organization,” and “grow your relationship.” It’s by the authors of Peak Performance (2017), a self-help book promising to deliver “the new science of success,” which argues that growth is growth, regardless of the activity, and begins from the assumption that growth is the only thing that counts as a goal.

Existential ambitions are formulated in such extreme and simple language that they appear like human universals, immune to situation, history and material conditions.Given these equivalencies, the old image of the climbing rat, as they are affectionately known, a kind of romantic, fit hobo obsessed with mountains rather than the traditional goals befitting a young man, is also disappearing:

So what makes a highly paid fashion designer quit her job, buy a Eurovan and move to Kentucky to serve pizza and climb every day? What possesses an engineer to become a climbing guide? Why would a professional pilot or an entomologist spend thousands of dollars and hours of their time establishing climbs for no reward except the honor of a first ascent and the ability to name the route? Why, indeed, would anyone sacrifice what most Americans understand as the “American Dream”—a career, a house, and material wealth—to live in a tent or car, and have no permanent employment or discernible future goals?

Posing these questions, climber Deborah Halbert forgets the extent to which climbing actually fits very well with the 21st-century “Dream,” no longer merely American since the end of the Cold War—not only in the sense that many climbers are professionals who do it for a living and get paid well enough to build wealth, but also insofar as today’s climbing body is more often than not presented as a convergence of the values of performance, speed and efficiency, in perfect compliance with fantasies of the individual who overcomes adversity and late capitalism’s demand for docile, transparent bodies.

The equating of climbing with success in business has been going on since at least the 1996 Everest disaster, during which eight people died on the mountain, including guides and officers from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police. The events of May 1996 were made famous by Jon Krakauer in his 1997 book Into Thin Air, and in the IMAX film Everest (1998). Scholars analyzing the media coverage of the event have described it as “the most widely publicized mountain-climbing disaster in history” and “the perfect story,” “a singular iconic subject that took on a life and meaning well beyond the circumstances that surrounded it,” something of a myth.

The 1996 disaster strengthened two things: the presence of the vicarious public, who could passively watch, discuss and judge the tragedy from the comforts of their living rooms, and a new framing of mountaineering as management. The belief that this disaster was a lesson in bad organization, team-work and shoddy management of personalities made it a favorite case study for corporate management education. Trainers and consultants still routinely appropriate the story to teach lessons in leadership and group dynamics.

But the logic that united climbing success with corporate success really blossomed when the third and final element entered the scene: the success of social and especially romantic relationships. That’s when climbing became synonymous with, more generally, the life worth living. And the 1996 Everest disaster was bookmarked by the releases of two Hollywood blockbuster films that had climbing as their backgrounds for suspense/action narratives: Cliffhanger (1993) and Vertical Limit (2000).

The films are shockingly similar in their narrative structures. Both begin with a dramatic rock-climbing fatality in which the male protagonist is implicated—he did what he thought was right, which resulted in someone falling horribly to their death. In both films, the protagonist responds to the tragedy by quitting climbing. And in both films, a situation unfolds that requires the protagonist to climb once more, to face the climbing challenge of his life, in order to save the life of a woman he loves. In Cliffhanger, that woman is our hero’s romantic partner, and in Vertical Limit, it’s his sister, but both films end with the final reward of a bright future in love. Climbing is winning at life and winning at life means happily ever after or “growing your relationship.”

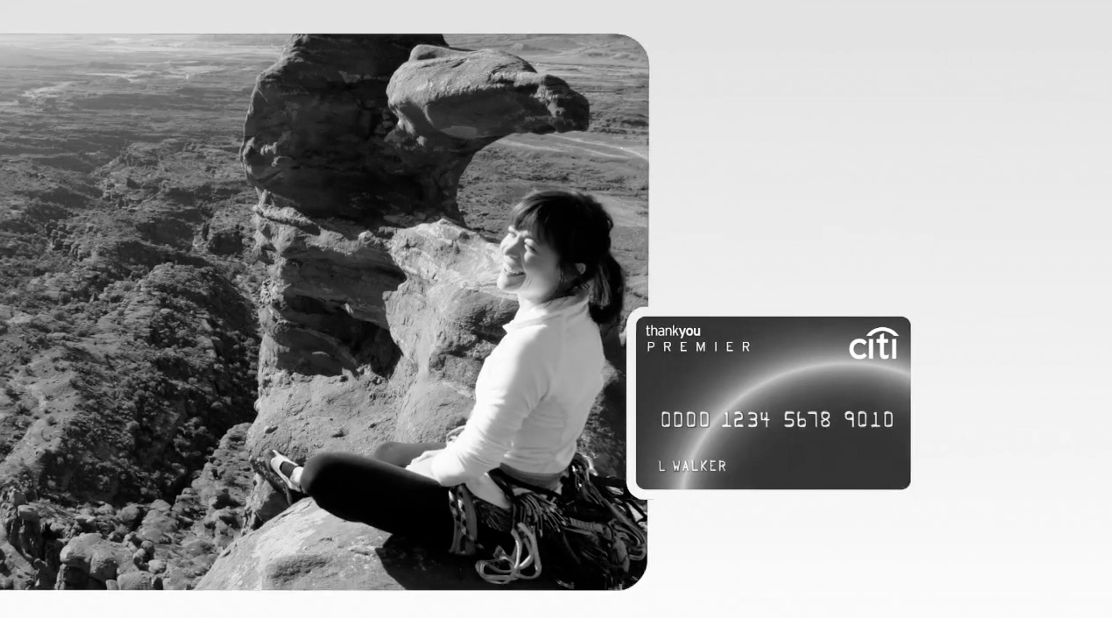

The equating of climbing with success in business has been going on since at least the 1996 Everest disaster, during which eight people died on the mountain.Another decade later, the 2011 Citibank ad starring top pro rock climbers Katie Brown and Honnold as a couple on vacation performs this logic brilliantly, with a voiceover that directly satirizes the objects of older credit card ads (shoes, belts and engagement rings) and replaces them with the freedom that rock climbing ostensibly brings.

“My boyfriend and I were going on vacation, so I used my Citi Thank You card to pick up some accessories.” The ad shows different kinds of climbing gear while her heavily vocal-fry-ed voiceover playfully lists them: “A new belt, some nylons, and… what girl wouldn’t need new shoes?” By now, the footage has cut to the “couple” climbing… “We talked about getting a diamond, but with all the thank you points I’ve been earning,”—and here, the rock music swells (“somebody left the gate open/come save us, a runaway train gone insane”) while spectacular drone footage makes clear that the “rock” in question is the one they are climbing.

Still from Citibank ad starring Katie Brown and Alex Honnold

Still from Citibank ad starring Katie Brown and Alex Honnold

While many pros like Honnold in fact built their careers while living out of cars and wholly rejecting a traditional life of work, credit-building and home equity, this ad performs a sleight of hand in which one forgets what the ad is for. The superimposing of climbing onto a credit line for a couple’s vacation creates a particular fantasy of what it takes to “have a life” today. Wealth-building and coupledom have become synonymous and they no longer appear compulsory, but as a glorious expression of freedom and human being itself.

More recent films continue to rely on the narrative structure in which “the climb” is both climbing and romantic love. One such example is The Climb (2017), a French romantic comedy which tells the true story of Nadir Dendoune, the first French-Algerian to summit Everest. Dendoune had no prior climbing experience, and made the attempt in order to prove himself to a woman he loves. Documentaries of important climbs repeat the same gesture. The Dawn Wall documents Tommy Caldwell’s romantic history alongside the historic climb, finishing with the triumph of his second marriage (this time, including a child) which aligns with his professional success. And while Free Solo is ostensibly built around the tension between Honnold’s real-life romantic relationship and his burning desire for El Cap—made spectacularly literal by the difference between the house the couple live in in Las Vegas and the van Honnold lives in when he is climbing—the film ends by reconciling this tension. Honnold’s climb is one glorious triumph across the board, as the girlfriend runs into the van and literally falls right into bed to welcome him back (not to mention that the couple tied the knot in 2020).

The more extreme mountain sports become, the more they are filmed, and the more these images are used to convince the vicarious public that to “grow your” is a universal, timeless human desire. Meanwhile, climbers continue to climb in pursuit of the very mountain thereness that unsustainable, bottomless economic growth continuously threatens.

*

In March 2020, both the Nepalese and Chinese governments announced that the 2020 climbing season was canceled due to the Covid-19 outbreak. Though people have been calling for a closing of Everest for several years now, this is the first time that such a closure has happened.

In the midst of the ongoing pandemic, as the media constantly announced its “second wave,” Nepal reestablished international flights and announced a new climbing season starting in August 2020. Reports predict the 2020-21 season will be busier and more crowded than ever, given the backlog of climbers who missed out the year before. But the temporary closure is a reminder that closures—even of mountains as lucrative as Everest—are possible. What if Everest went the way of Uluru and were closed to climbers forever?

More recent films continue to rely on the narrative structure in which “the climb” is both climbing and romantic love.Such a move would be more complicated than it appears, and the complications are dramatically different for the different communities it would affect. The loudest protests would undoubtedly come from climbers themselves—but not the most skilled ones, who already have access to, and in many cases more interest in, the less frequented Himalayan peaks. On the contrary, if the “Everest selfie” phenomenon is any indication, the greatest emotional impact would be on climbers for whom Everest is the best or only Himalayan opportunity.

Correspondingly, however, the greatest economic impact would be on the local Sherpa support economy that has been built around Everest. Sherpas are pro climbers in the truest sense—paid to guide others into the world of Everest—and many of them die while doing their job. Any moves to permanently close off the summit or dramatically lower the number of permits issued each year would have to seriously consider the effect on Sherpa communities, currently engaged in their own debates about their future as climbers. Large-scale relocations might be undertaken, as if a natural disaster had occurred.

In a sense, though, a natural disaster is precisely what has already happened. This disaster consists not just of the traffic jam at the top or the high death count. It encompasses a vulnerable mountain environment that has ballooned with economic growth. Due to climate change, the Himalaya could lose more than a third of their glaciers by the end of the century. This could have devastating consequences for the 1.65 billion people living in the mountains and in downstream countries, who are at risk of flooding and the destruction of crops. Between Himalayan warming (growth at its most abstract and hardest to mitigate) and the “zoo” and “garbage dump” on Everest (growth at its most obvious and tangible), the scale and complexity of the recent damage to the region is only now beginning to come into view. Everest is living proof, if you will, that the limits of human desire for the good life have finally reached “the top,” the limits of what the world can handle. Ironically, it has taken some of the best climbers to bring this to the world’s attention.

__________________________________

From Mountains and Desire: Climbing vs. the End of the World by Margret Grebowicz. Used with the permission of Repeater. Copyright © 2021 by Margret Grebowicz.