Why AI Can’t Properly Translate Proust—Yet

Michael Wooldridge on the Limits of Literary Automation

Deep learning has proved to be enormously successful, in the sense that it has enabled us to build programs that we could not have imagined a few years ago. But laudable as these achievements genuinely are, they are not a magic ingredient that will propel AI toward the grand dream. Let me try to explain why. To do this, we’ll look at two widely used applications of deep learning techniques: image captioning and automated translation.

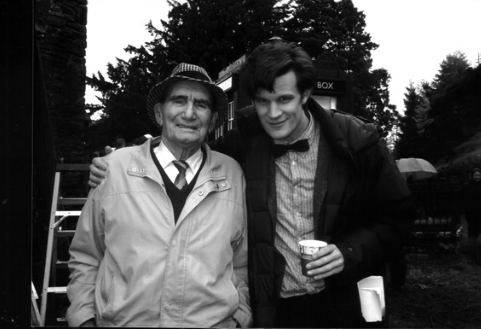

In an image-captioning problem, we want a computer to be able to take an image and give a textual description of it. Systems that have this capability to some degree are now in widespread usage—the last update of my Apple Mac software gave me a photo management application that does a decent job of being able to classify my pictures into categories like “Beach scene,” “Party,” and so on. At the time of writing, several websites are available, typically run by international research groups, which allow you to upload photos and will attempt to provide captions for them. To better understand the limitations of current image captioning technology—and hence deep learning—I uploaded a family picture to one (in this case, Microsoft’s CaptionBot)—the photo is shown in figure 13.

Figure 13: What is going on in this picture?

Figure 13: What is going on in this picture?

Before examining CaptionBot’s response, pause for a moment to look at the picture. If you are British or a fan of science fiction, then you will very probably recognize the gentleman on the right of the picture: he is Matt Smith, the actor who played the eponymous Doctor Who from 2010 to 2013 in the BBC television show. (You won’t recognize the gentleman on the left—he is my late grandfather-in-law.)

CaptionBot’s interpretation of the picture was as follows:

I think it’s Matt Smith standing posing for a picture and they seem :-) :-)

CaptionBot correctly identified a key element of the picture and went some way to recognizing the setting (standing; posing for a picture; smiling). However, this success can easily mislead us into thinking that CaptionBot is doing something that it most certainly is not—and what it is not doing is understanding. To illustrate this point, think about what it means for the system to identify Matt Smith. As we saw previously, machine learning systems like CaptionBot are trained by giving them a very large number of training examples, each example consisting of a picture together with a textual explanation of the picture. Eventually, after being shown enough pictures containing Matt Smith, together with the explanatory text “Matt Smith,” the system is able to correctly produce the text “Matt Smith” whenever it is presented with a picture of the man himself.

But CaptionBot is not “recognizing” Matt Smith in any meaningful sense. To understand this, suppose I asked you to interpret what you see in the picture. You might come back with an explanation like this:

I can see Matt Smith, the actor who played Doctor Who, standing with his arm around an older man—I don’t know who he is. They are both smiling. Matt is dressed as his Doctor Who character, so he is probably filming somewhere. In his pocket is a rolled-up piece of paper, so that is likely to be a script. He is holding a paper cup, so he is probably on a tea break. Behind them, the blue box is the TARDIS, the spaceship / time machine that Doctor Who travels around in. They are outdoors, so Matt is probably filming on location somewhere. There must be a film crew, cameras, and lights somewhere close by.

CaptionBot wasn’t able to do any of that. While it was able to identify Matt Smith, in the sense of correctly producing the text “Matt Smith,” it wasn’t able to use this to then interpret and understand what is going on in the picture. And the absence of understanding is precisely the point here.

Apart from the fact that systems like CaptionBot only have a limited ability to interpret the pictures they are shown, there is another sense in which they do not, and currently cannot, demonstrate understanding of the kind that we can.

When you looked at the picture of Matt Smith dressed as Doctor Who, you would probably have experienced a range of thoughts and emotions, above and beyond simply identifying the actor and interpreting what was going on. If you were a Doctor Who fan, you might have found yourself reminiscing fondly about your favorite episode of Doctor Who with Matt Smith in the title role (“The Girl Who Waited,” I hope we can all agree). You might have remembered watching Matt Smith as Doctor Who with your parents or your children. You might have remembered being scared by the monsters in the program, and so on. It might remind you of an occasion where you were on a film set or saw a film crew.

Understanding means more than being able to map a certain input to a certain output. Such a capability may be part of understanding, but it isn’t by any means the whole story.

Your understanding of the picture is therefore grounded in your experiences as a person in the world. Such an understanding is not possible for CaptionBot, because CaptionBot has no such grounding (nor, of course, does it purport to). CaptionBot is completely disembodied from the world, and as Rodney Brooks reminded us, intelligence is embodied. I emphasize that this is not an argument that AI systems cannot demonstrate understanding but rather that understanding means more than being able to map a certain input (a picture containing Matt Smith) to a certain output (the text “Matt Smith”). Such a capability may be part of understanding, but it isn’t by any means the whole story.

Automated translation from one language to another is another area in which deep learning has led to rapid progress over the past decade. Looking at what these tools can and cannot do helps us to understand the limitations of deep learning. Google Translate is probably the best-known automated translation system. Originally made available as a product in 2006, the most recent versions of Google Translate use deep learning and neural nets. The system is trained by giving it large volumes of translated texts.

Let’s see what happens when the 2019 iteration of Google Translate is given an unreasonably difficult problem: translating the first paragraph of À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time), the classic early-20th-century novel by the French author Marcel Proust. Here is the first paragraph, in the original French:

Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure. Parfois, à peine ma bougie éteinte, mes yeux se fermaient si vite que je n’avais pas le temps de me dire: “Je m’endors.” Et, une demi-heure après, la pensée qu’il était temps de chercher le sommeil m’éveillait; je voulais poser le volume que je croyais avoir encore dans les mains et souffler ma lumière; je n’avais pas cessé en dormant de faire des réflexions sur ce que je venais de lire, mais ces réflexions avaient pris un tour un peu particulier; il me semblait que j’étais moi-même ce dont parlait l’ouvrage: une église, un quatuor, la rivalité de François Ier et de Charles Quint.

I’m embarrassed to say that, despite the decade-long efforts of a hardworking group of language teachers, I understand very little French: I can make out only the odd isolated phrase in the above text, and without help, I have no sense whatsoever of what the entire text means.

Here is that first paragraph, translated into English by a professional translator:

For a long time I used to go to bed early. Sometimes, when I had put out my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had not even time to say “I’m going to sleep.” And half an hour later the thought that it was time to go to sleep would awaken me; I would try to put away the book which, I imagined, was still in my hands, and to blow out the light; I had been thinking all the time, while I was asleep, of what I had just been reading, but my thoughts had run into a channel of their own, until I myself seemed actually to have become the subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V.

Much better! But interestingly, although this is beautifully written English, the meaning is still not completely transparent, not to me, at least. What does the author mean when he writes, “I . . . seemed actually to have become the subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V”? How can you “become” a church? What does he mean by a “quartet”? What “rivalry” between François I and Charles V is he referring to? And for someone that uses electric lighting: What does it mean to “blow out” a light?

Now let’s see what Google Translate made of it:

Long time, I went to bed early. Sometimes, when my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had no time to say: “I fall asleep.” And half an hour later the thought that it was time to go to sleep would awaken me; I wanted to ask the volume that I thought I had in my hands and blow my light; I had not ceased while sleeping to reflections on what I had read, but these reflections had taken a rather peculiar turn; I felt that I myself was what spoke the book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between Francis I and Charles V.

This is recognizably the same text as the professional translation, and so Google Translate is doing something sophisticated. But you don’t have to be a professional translator, or an expert on literature, to see its limitations. The expression “blow my light” makes no sense in English, and the sentences that follow don’t make sense either. Indeed, they are rather comical. And the translation includes phrasings that a native English speaker would never use. The overall impression that we are getting is of a recognizable but unnaturally distorted version of the text.

Of course, we gave Google Translate an unreasonably difficult problem—translating Proust would be a huge challenge even for a professional French-to-English translator. So why is this, and why is it so hard for automated translation tools to tackle?

The point is that a translator of Proust’s classic novel requires more than just an understanding of French. You could be the most competent reader of French in the world and still find yourself bewildered by Proust, and not just because of his frankly exhausting prose style. To properly understand Proust—and hence to properly translate Proust—you also need to have a great deal of background knowledge. Knowledge about French society and life in the early 20th century (for example, you would need to know they used candles for lighting); knowledge of French history (of François I and Charles V and the rivalry between them); knowledge about early-20th-century French literature (the writing style of the time, allusions that authors might make); and knowledge about Proust himself (what were his main concerns?). A neural net of the type used in Google Translate has none of that.

This observation—that to understand Proust’s text requires knowledge of various kinds—is not a new one. We came across it before, in the context of the Cyc project. Remember that Cyc was supposed to be given knowledge corresponding to the whole of consensus reality, and the Cyc hypothesis was that this would yield human-level general intelligence. Researchers in knowledge-based AI would be keen for me to point out to you that, decades ago, they anticipated exactly this issue. (The sharp retort from the neural nets community would then be that the techniques proposed by the knowledge-based AI community didn’t work out so well, did they?) But it is not obvious that just continuing to refine deep learning techniques will address this problem. Deep learning will be part of the solution, but a proper solution will, I think, require something much more than just a larger neural net, or more processing power, or more training data in the form of boring French novels. It will require breakthroughs at least as dramatic as deep learning itself. I suspect those breakthroughs will require explicitly represented knowledge as well as deep learning: somehow, we will have to bridge the gap between the world of explicitly represented knowledge, and the world of deep learning and neural nets.

__________________________________

A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence by Michael Wooldridge is available now via Flatiron Books.

Michael Wooldridge

Michael Wooldridge is the Head of Department of Computer Science at the University of Oxford. He has been an AI researcher for more than 30 years, and in 2021 was the recipient of the Outstanding Educator Award from the Association for the Advancement of AI (AAAI). His book, A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence, is published by Flatiron Press on 19 January 2021.