Claire

I’ve already told the whole story ten times to the people you work with, you could just read my file.

I know you’re new, I can see that for myself. Is this your first job? Because you must be only thirty, at the very most.

You don’t look it.

I’m laughing because here I am reciting Marivaux to you and you have no idea. Have they still not put literature on the curriculum in this place?

You can tell from, I don’t know, the rhythm, the intonation. It’s your job to hear how things sound. To spot anything that doesn’t ring true. Ding dong. Cuckoo! Hmm, yes, completely cuckoo.

Araminte. The beautiful widow. And we don’t know whether her young steward wants to seduce her because he loves her or because she’s rich. Whether he’s sincere even though he’s manipulating her. But you’re no Dorante, I’m guessing you’re not here because you have any plans to marry me?

I’ve done a bit of acting, yes, in my day—it was a long time ago. My husband was a director—well, is. He carried on. We were students when we met, we were in the university theater group. It seems such a long time ago. And yet, d’you know, I still remember some of my lines by heart. I’ve also learned a bit about staging a performance, haven’t I? But let’s not go back to the flood of tears. Anyway, it’s all been written up in there, in your paperwork. What more do you want?

You need to understand? Oh, I understand that! But what exactly do you want to understand?

Well, that’s a hell of an answer. You score a point. What’s your name?

Marc. Marc. I like you, Marc, and I agree with you: there are only two interesting people in each of us, the one who wants to kill and the one who wants to die. They’re not equally well represented, but when you’ve identified them both you can say you’ve gotten to know someone. It’s often too late.

* * * *

How did we end up here? We? Kind of you to include yourself in this disaster, when you’ve only just turned up. No one can blame you for the situation I’m in, I’ve “ended up in,” if I can actually be said to have moved in the last two, um, three years—is it two and a half years?—that I’ve been here. Or maybe when you say “we” you mean a more general they-we-you? Us all? We, the institution. We, the specialists. We, society. How did we manage to get into a situation where this woman here present is still living at public expense, where she hasn’t accepted her duties, her obligations, her productivity, or should that be reproductivity? So that in her later years she’ll be fed, housed, cared for, and given medical care by us rather than doing what she’s certainly still capable of doing for the community? Where did we fuck up? Is that your question?

I taught. Pretty taut I got too, sometimes.

At university, yes, comparative literature. Senior lecturer. I was about to get my professorship. This they-we-you of yours were about to promote me, to allow me into the wonderful world of mandarins. At forty-seven, they-we-you could say that I was a role model for women, you know there’s still a ridiculously low proportion of women in higher positions. And then bang! What a drag! They lock me up, they cross-examine me, and, till now, they keep me here. Will you keep me here, Marc? Will you keep me near you? I’m useless here, I’m not making my contribution to society. I’m deceased in the purest sense of the word, I’ve ceased to be. Yes, that’s it, I’m no longer operational, I’ve blown a fuse, if you like, or blown a gasket, tripped a switch, and whee! I’ve spun out of control, I’m effectively dead and it’s your job to resuscitate me, to rewire my circuits, get the machine working again and basically reinstate me. That is what you do, isn’t it?—reinstate people. You want the deceased to function again. Which reminds me, there’s something I wanted to tell you: you summoned me this mor—What is it? You don’t like “summoned”? Okay. You invited me here this morning, it’s eleven o’clock, I’m telling you that for future reference, if there is to be any future reference, I’m not really a morning person, not very operational, I can’t get up, I’m knocked out by the Valium from the previous evening, and not yet soothed by the daily Xanax, and anyway quite often (this is a secret, don’t tell anyone), quite often I don’t take it, I’d rather be anxious than oblivious, if you’re unhappy it’s better to know you are, wouldn’t you say?

* * * *

In the early days it had nothing to do with Chris—with Christopher—because I’m guessing it’s Christophe you want me to talk about? The corpus delicti or rather the corpus so absolutely delectable he broke my heart. Or would you prefer me to talk about my childhood, my parents, my family—the whole shebang?

It wasn’t Chris I was trying to get to at all, at first. I didn’t know him, I wasn’t interested in him. I asked him to be my friend on Facebook just to have news of Joe—Joel. I was going out with Joel, with Joe, at the time. In those days Joe had hardly any friends on social networks, he only accepted people he knew, except me—he thought lovers shouldn’t be friends. But Chris (and it was Joe who told me this), well, Chris had hundreds of friends, he did a lot of Facebooking, his profile name was KissChris, he had this way of collecting likes so easily it impressed Joe. Are you on Facebook, Marc? You do understand what I’m talking about? You don’t need me to translate?

Anyone who’s been around Joe for a while might think it was weird for him to be shy like that because in other ways he had no boundaries, I mean really none—hardly even the one that would stop you killing someone outright if you got the urge, and even then. . . there are so many ways of killing someone. He could destroy you in a flash, with one word, with his silence. You must know that women’s main fear is abandonment? Yes, you have stuff like that in your books. Well, Joe was like that—I guess you could say “perverse”: he could abandon you ten times a day. He knew where the crack in your armor was—in a way, perverts know women best of all—and he would wedge the tip of his absence in there and just drain your vital energy, your thirst for happiness. You could reach out your hand to him, he’d squeeze it then drop it, on a whim, for no apparent reason, just because you were relying on him, you were relaxing into a feeling of trust. Toward the end I stopped telling him what I liked, I didn’t let him know what made me happy because he would have gone to considerable lengths to avoid it or to make sure it didn’t happen. When I couldn’t take any more I’d leave him, but I never got out completely. And he’d come back all sugary sweet or I’d call him back all honeyed words and the cycle started again, month after month. Don’t ask me why. I’d just separated from my husband, I didn’t want to be alone, I needed love, or at least to make love, to talk about it, believe in it, well, you must know that song, everyone wants to live, do we need to say why?

No, never. Joe never hurt me physically. It wasn’t worth it. Physical cruelty’s a last resort, thumping someone in the face is for beginners.

Hard to say. Desire works in mysterious ways. You want something from the other person that you yourself don’t have or no longer have. Before I would have said you always want the same thing—a good deep-seated thing from the past, even if it’s harmful. Rekindling heartache. Refueling the flamethrower. But since this relationship, I’m not so sure. I’ve come to think desire might be able to change, that you could uproot it, plant it into new, softer, more accommodating soil. At least try. If everything’s written in advance, that would be too sad, I thought. If the die is cast what’s the point trying to change the numbers?

Yes. So it was during one of our long breaks, I just couldn’t take not knowing where Joe was any longer—because he could vanish, completely vanish—I set up a fake Facebook profile. Till then I’d hardly used it, I had a profile with my real name, Claire Millecam, it was for work, I exchanged information with foreign academics or former students, every now and then, no great shakes. Then I fell into the trap. For people like me who are terrified of being abandoned—that’s what you’ve got written there, haven’t you, terrified of being abandoned? Basically a bit like a food allergy: too much abandonment and I’m heading for anaphylactic shock, I suffocate and die—for people like me the Internet is the shipwreck as well as the life raft: you drown in the tracking game, in the expectation, you can’t grieve for a relationship, however dead it may be, and at the same time you’re hovering above it in a virtual world, clinging to fake information that pops up all over the Web, and instead of falling apart you go online. If only for that little green light that tells you the other person’s online. Ah, that little green light, what a comfort! I remember that. Even if the other person ignores you, you know where they are: he’s there on your screen, he’s sort of grounded in time and space. Especially if next to the green light it says “Web”: then you can imagine him at home, sitting at his computer, you have a mooring in the wild sea of possibilities. What makes you more anxious is when the green light says “mobile.” Mobile, don’t you see?! Mobile means on the move, roaming, free! By definition, harder to situate. He could be anywhere with his phone. Still, you know what he’s doing, or at least you feel you do—and this creates a sort of proximity which has a calming effect. You reckon that if he was enjoying what he was doing he wouldn’t be going online every ten minutes. Maybe he’s watching you too, hiding behind the wall and watching what you’re doing? Kids spying on each other. You listen to the same songs as him, almost in real time, you live together through music, you even dance to the same songs that get him tapping his feet. And when he’s not there, you have a record of when he was last online. You know what time he woke up, for example, because looking at his wall seems to be the first thing he does. At what point in the day he laid eyes on a photo he commented on. Whether he woke in the middle of the night. He doesn’t even need to say so. Basically, you’re stitching this together as you go along: you embroider over the gaps, like darning socks. There’s a good reason for calling it the Web. One minute you’re a spider, the next you’re a fly. But you exist for each other, thanks to each other, connected by a shared religion. Not exactly taking communion, but communing.

Of course it hurts too, of course it does: the other person’s online, but not with you. You can imagine all sorts of things, you do imagine all sorts of things, you look at his new friends’ profiles—both male and female—looking for a revelation in someone’s posts; you decipher the tiniest comment, you keep cutting from one wall to another, you play back the songs he’s listened to, read meaning into the lyrics, learn about what he likes, view his photos and videos, keep an eye on his geo-location, the events he’s going to, you navigate like a submarine through an ocean of faces and words. Sometimes it takes your breath away, you stand there holding your breath on the edge of this abyss to which you’ve been relegated. But it’s not as painful as knowing nothing, nothing at all, being cut off. “I know where you are”: I needed those words in order to live, do you understand? It’s like that epitaph on an American’s tomb at Père-Lachaise cemetery—I used to love strolling around there. His wife had had this engraved: “Henry, at last I know where you’re sleeping tonight.” Wonderful, isn’t it?! Facebook’s a bit like that: okay, so the other person’s alive, but he’s assigned a location, he’s not entirely free, he’s on known territory, even if it isn’t conquered territory. So that little green light kept me alive like a drip, a lungful of Ventolin, I could breathe easier. And at night it was sometimes my guiding star. I don’t have to explain that. It’s a statement of fact. I had a bearing in the middle of the desert, a reference point. Without it I’d be dead. D’you understand? Dead.

And you can go ahead and do what the others did, deducing that I had God knows what sort of fusional relationship with my mother, an inability to break away, a castration complex and everything else. But then don’t go saying in the same breath that I had the means—that I have the means—to move on to something else: my work, my friends, my children. I was the child. Okay? I am the child. There’s no specific age for being a kid. You must have that written somewhere in the file, that I’m the child?

What is a child? How can I put this . . . It’s someone who needs looking after.

It’s someone who wants to be cradled.

Even if it’s an illusion, yes, why not? It’s still just as soothing. Ha, now you’re pleased with yourself! Nice line: even if it’s an illusion? In a smooth voice. Are you a doctor or just a psychologist? Mind you, what’s the difference? What I don’t like about your discipline, your so-called science, is that it doesn’t change anything. However much we understand what’s going on, what’s gone on, we’re still not saved. When we understand what’s causing our pain, it still hurts. No benefit. We can’t be cured of our failures. You can’t darn ripped sheets.

Are you on Facebook, Marc? You’re not answering.

You’re not proud of it. You don’t stalk people, do you. You get enough from your job.

So anyway, because I couldn’t follow Joe directly, I sent Chris, KissChris, a friend request. He was the perfect contact because he’d recently moved into Joe’s apartment, although only intermittently. They’d met about ten years earlier in the editorial department of Le Parisien, where they both worked, Chris as a photographer, Joe as an intern, they were about twenty-five at the time. I got the impression they did a lot of partying together for two or three years before having a bust-up over work, a girl, some weed, or money. And then, at the time I’m talking about, they’d just reconnected through some other guy who patched things up between them. Chris was struggling, every now and then he’d get some minor reportage, a photo for a scummy magazine, but he mostly lived on benefits. Meanwhile Joe was happily unemployed and about to move into his family’s holiday house in Lacanau, near Arcachon—a dreamy place where I had, where I still have, wonderful memories: time passes, the memories remain, as cemeteries say. Because there were good times with Joe. A few. Maybe there are good times with everyone. There can be. His parents inherited a fortune from a childless cousin, money wasn’t a problem for him anymore. He vaguely made music—nothing serious—but his mother was keen for him, aged forty, to maintain some semblance of work: so he was the caretaker and the gardener and the plumber and the electrician. Or so to speak, because he couldn’t do any of those things. He couldn’t bear being on his own and, because I lived in Paris, I couldn’t go see him very often (I sometimes think that was the main reason he finally moved out to the country: to make it difficult for me to see him), so he offered to put Chris up. Marguerite Duras wrote something about that, about the fact that men really like being among men, do you see what I mean, there’s a sort of laziness, a lack of interest in women—too different, too tiring. Women require an effort that they don’t feel like making, not long term anyway. Except for fucking, I guess. They bolster each other with their mutual virility, they don’t want a woman inside their heads or right in front of their faces. I imagine Joe was also thinking he could resuscitate his younger days, start over. He could never deal with the idea of growing old. In his own mind he was still eighteen, he fantasized about very young girls, minors, virgins—did you know that the combination of “teen” and “sex” is the most common Google search in the world?—well, basically, he thought you could keep playing the same film over and over. That’s what they did, anyway. Chris moved in with Joe, like in the good old days.

I’d never met Chris in the flesh. Joe had told me a few things about him, that was all. I think he didn’t want me to meet him: he hid it well but Joe was extremely jealous, he was always frightened of losing what he had, including what he didn’t want. If he’d lost something everyone had to lose it, if something was dead as far as he was concerned, it couldn’t keep going someplace else. One of the last times I saw Joe in Paris before the meltdown, he just showed me the photos Chris was taking and posting on Facebook to drum up some interest, make a bit of buzz, as he called it. He wasn’t very kind about his “best buddy”; according to him, Chris wasn’t really looking for a job. He was fed and housed in Lacanau, so why move? Then his ambition was to become famous without lifting a finger—maybe just his index finger to press the start button. “He’s hoping someone will notice him one day and turn him into the next Depardon,” Joe scoffed. His photos were good, I looked at them in detail, but only because it was a way to spend time with Joe.

Chris? No, I never actually spoke to him, before. Well, yes I did, it came back to me the other night, I had a nightmare and the words came back to me, should I tell you this? You’re interested in nightmares? Okay. It was morning, I had a lecture, I went into the amphitheater, all dressed up, nice makeup, I headed for the podium and just then all the seats emptied in a flash, all the people were wearing blue, they got to their feet as a block, clumped noisily down the stairs, and walked out without even glancing in my direction, a thumbs-down, and I was left alone on my platform, an empty platform and not a train in sight. I was frightened, I turned around and there was something written on the board in capitals, in capital punishment, I woke with a start, my heart pounding at a hundred miles an hour, and there were those words, now here you could make a note, get your pen, this won’t be in the file. No? Don’t you have to write everything down, even tiny details? Aha, listening! Big Brother’s listening! Well, the dream reminded me of something in real life. One evening I called Joe in Lacanau, I often did to keep things going—keep our love going, what was left of it. He mostly didn’t answer but that evening he did. He’d been drinking or smoking, both probably, either way he was hazy and aggressive, he complained I was checking up on him, calling him only to be sure he was there, to monitor him. And then—and this is something he did if he was bored with a conversation, sometimes in the middle of the street with a random passerby—he handed me to someone else without any warning. Suddenly, in the middle of a sentence I heard a different voice, an unfamiliar voice saying hi, then calm down. It was Chris, I realized afterward. I complained, got angry, this habit of Joe’s irritated me, even if sometimes it really made me laugh when he stopped complete strangers in the street . . . But not this time, the guy on the other end wasn’t funny, talking to me like we knew each other, his voice slurred and patronizing, Don’t you think you’re a bit old to be jealous? he said. I got real mad, I asked to speak to Joe again, She’s so not cool this chick of yours, he muttered and then said pompously: So you think you can do whatever you like, you think whoever can call at whatever time of day. I’m not just anybody, I retorted. And at least not squatting, I’m not sponging off him. At that point I heard him take a toke, then he blew out the smoke and before hanging up—without handing me back to Joe—he said: Go die!

Go die.

The killer words.

People throw themselves out of windows for less than that, don’t they? Plenty here would. They’ve been bashed around by so many words they start to wobble.

Go die. GO DIE. Other people’s words follow them around like hostile ghosts. People’s voices issue instructions they can’t escape. Textual harassment, you could say, ha ha! I like word games too, you see. We should get along.

Anyway, all that to explain that there was absolutely no way I could have predicted what happened next. When I set up my fake Facebook page, Chris was just a parasite as far as I was concerned, a rude misogynistic freeloader, an enemy in my shaky relationship with Joe. I wasn’t even considering communicating with him, I just wanted this indirect access to news of Joe.

Go die.

That’s what I ended up doing when it comes down to it, didn’t I?

In the end I did as I was told. I’m not alive here. Is that what you all think? When you’re crazy the imperative sounds like an incontrovertible command, doesn’t it? Tell me, is that what you all think? A command that can be turned around too. Oh, go on. That can be sent back to the sender. Go die yourself. When you’re crazy. When a woman’s crazy.

And is that what’s written there, that I’m crazy? Are all women crazy?

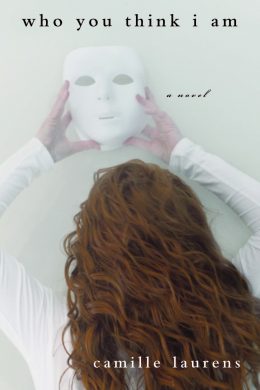

From WHO YOU THINK I AM. Used with permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2017 by Camille Laurens, translation by Adriana Hunter.