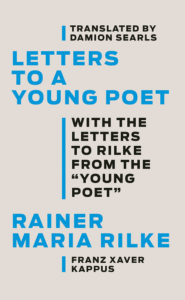

Who Exactly Was Rilke's Young Poet Correspondent?

Damion Searls on Translating Letters to a Young Poet

(and the Young Poet's Letters)

Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet has spoken powerfully, and differently, to every generation of readers since they were first published in German in 1929. They have been seen as a record of the great man’s own development, written to a “Young Poet” but also by a young poet going through serious personal and artistic crises of his own. (Rilke had recently turned twenty-seven when he wrote his first letter.) They have been taken as a spiritual guide, a source of insight, inspiration, and encouragement for any young person struggling with loneliness and doubt, questions of his or her fate and of what interpersonal and sexual relationships might have the potential to be. They were an inspiration to Marilyn Monroe, Jane Fonda, and the inventor of the programmable computer, who bought the book in 1929; Dustin Hoffman called it his bible; Lady Gaga had a line from it tattooed on her arm.

Today, even though the Letters to a Young Poet have been in print for nearly a century and translated into English more than half a dozen times, we have the chance to see them afresh, in a genuinely new way, with the discovery and publication of the other half of the story: the letters that the “Young Poet,” Franz Xaver Kappus, wrote to Rilke. In this edition, the Letters to a Young Poet are for the first time a two-way conversation, a true dialogue.

As recently as 2018, scholars and translators were saying in print that these letters to Rilke did not survive, but in fact they’ve been in the private Rilke family archive in Germany all along, waiting for someone to find them. A Rilke scholar named Erich Unglaub got permission from Rilke’s heirs to look at Kappus’s letters from the archive, and the press Wallstein Verlag published them in German for the first time in March 2019. Their translation would not have been possible without Erich Unglaub’s and Wallstein Verlag’s generous assistance, and I would like to thank them both.

Unglaub’s edition of the missing half of the correspondence solves several mysteries of Letters to a Young Poet. It turns out that Rilke and the Young Poet did meet in person. We now know more of what lay behind the long gap in the correspondence between 1904 and 1908. This information is in my biographical afterword. There is even a lost eleventh letter from Rilke, though only tantalizing glimpses of it remain.

More importantly, Rilke’s pronouncements from on high have turned into answers, sensitively directed not just toward young aspiring artists in general but at a very particular person we can now see clearly.

It turns out that Rilke and the Young Poet did meet in person. We now know more of what lay behind the long gap in the correspondence between 1904 and 1908.

It has been easy to think that Rilke was writing his letters to a kind of younger version of himself—it’s now clearer that Kappus was quite a different person. The connections between Rilke and Kappus are ones that Rilke largely creates, rather than finding them ready-made in their life histories. And while many of the topics in the Letters to a Young Poet are actually introduced by Kappus—irony, sex, uncomprehending relatives, the loss of a sense of God—there are others that Rilke declines to take up (for example, many literary matters, including questions about his own works, which he leaves to Kappus to read for himself), as well as things he chooses to bring up on his own (such as his feminist discussion of women’s identity). Rilke’s message is the same whether or not we read Kappus’s letters, but with the full correspondence it is much easier to see Rilke’s priorities: what he thinks is important and how he thinks it will speak to his reader.

Rilke’s emphasis on solitude in Letters to a Young Poet has also been easy to overplay—the biographical facts, with Rilke often living separately from his wife and having more or less abandoned their infant daughter, certainly cast him as an arrogant and needy rejecter of intimacy. But what will be interesting to today’s generation of readers, I feel, is how Rilke’s advice to Kappus addresses the interplay between inner and outer, between going into oneself and achieving a more intimate contact with the outside world and other people.

Rilke’s solitude was one that paradoxically—or perhaps not so paradoxically—let him speak to individual readers with extraordinary intimacy. The American poet Robert Hass said of Rilke: “His poems have the feeling of being written from a great depth in himself. What makes them so seductive is that they also speak to the reader so intimately. They seem whispered or crooned into our inmost ear.” As someone else once wrote, “It is as though one were reading the work inside oneself, so much does it arise from the depths of our intimate experience.” Except that was Marcel Proust. Giving a perfect description of his own writing, except he was actually describing Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, whose voice Proust found so remarkable that at one point he considered translating Walden into French. (Walden by Proust—imagine!)

All three of these writers were deeply indebted to Ralph Waldo Emerson—Thoreau personally; Proust’s first book quotes Emerson many times and is overwhelmed by his influence; Rilke got his Emerson largely through Nietzsche, also very much an Emerson disciple in his early writings. Rilkean “solitude” is as complex, and ultimately social, as the “self-reliance” championed by Emerson. In an urban, industrial world seeming to lack satisfactory religious answers to the ultimate questions, all these figures felt the need to look within themselves for forces and truths that could connect them to other people. They found spaces to retreat to—a cabin in the Massachusetts woods, a cork-lined room in Paris, or the more abstract vastness Rilke describes so often in these letters—and they did so, yes, to avoid other people, but also to reach them.

As Rilke argues in Letter Eight, what seems to impinge from without actually emerges from within. His concern with how to do artistic work, and his focus on solitude—the two main centers of gravity in earlier readings of the Letters to a Young Poet—are linked by an even more central piece of advice: that the Young Poet wait. From the very beginning, what Rilke praises is “quiet, hidden beginnings”; in Letter Four, he tells Kappus, “Don’t look for the answers now: they cannot be given to you yet because you cannot yet live them”; he ends their main correspondence with “the same as what I’ve said before—: I hope that you can find in yourself enough patience to endure these things.” The point of solitude is to give yourself time to grow in your own way, while the ultimate goal remains the difficult task of love and connection.

To go with the literal dialogue in this new edition, I have translated Rilke’s prose into a more straightforward voice than he is often given in English. This direct, vigorous style, together with the presence of Kappus’s letters, is meant to give readers a better sense of Rilke the real person, in real conversation.

Rilke’s message is the same whether or not we read Kappus’s letters, but with the full correspondence it is much easier to see Rilke’s priorities: what he thinks is important and how he thinks it will speak to his reader.

All the old pleasures of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet are still here. Readers have always felt Rilke talking directly to them, and the fact that he is answering someone else’s questions, responding to someone else’s problems, should not detract from this sense of personal connection. And since the Young Poet’s letters are simply not as good as Rilke’s—how could they be?—they both make Rilke’s empathy and artistry more impressive and risk interrupting it. The editors and I have therefore put Kappus’s letters in a separate section, to encourage readers, especially new readers, to experience Rilke’s iconic ten letters as the single work of art they have always been. Those interested in the dialogue with Kappus can flip back and forth to follow the correspondence in order.

Other translations of the Letters to a Young Poet tend not to include footnotes, and for good reason. What Rilke himself doesn’t explain to his less knowledgeable correspondent about, say, the writers he’s recommending is not really worth explaining; the magic of place names like “Viareggio” or “Borgeby Gård, Flädie,” is more evocative and powerful than factual information about what Rilke was doing in Italy or Sweden. Kappus, however, mentions more things and drops more names, and the existence of Kappus’s letters grounds the whole correspondence more firmly in time and place. So the present edition does include minimal notes in the back, mostly to Kappus’s letters.

This is the first complete edition in English, or nearly complete: only the Young Poet’s first letter to Rilke was missing from the Rilke family archive. In the autumn of 1902, Franz Xaver Kappus, a nineteen-year-old cadet at the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt, Austria, was reading a book of Rilke’s poetry when a passing professor caught sight of it and told Kappus that he had taught the poet himself at a lower school more than ten years before. Encouraged by the personal connection, Kappus wrote to Rilke, sending him copies of his own fledgling poems and pouring his heart out for advice. “Never before and never again in my life,” he would later write, “did I reveal myself to another person as openly and unreservedly as in that first letter to him.” A few months later, Rilke answered.

__________________________________

From Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Damion Searls. Used with the permission of Liveright Publishing.

Damion Searls

Damion Searls studied philosophy at Harvard and is a prominent translator from German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch, including of books by Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Rilke, Proust, Victoria Kielland, Saša Stanišić, Jelinek, Mann, Modiano, and Jon Fosse. His own writing includes fiction, poetry, and a widely translated biography of the creator of the Rorschach test.