White Sugar, Black Bodies: How Slavery Fueled an 18th-Century British Obsession

Mathelinda Nabugodi Explores the Violent Shared History of a Popular Consumer Product and Colonial Power in the Caribbean

We are in the Old Library of St. John’s College, Cambridge. One of the richest colleges in the world, its solid stone walls and parapets drip with the grandeur of old wealth. Various rumors about the college add to its aura of exclusivity. It is allegedly the only place other than the Royal Court where you are allowed to serve swan at table. Once a year the male fellows wear a black armband to mourn the day when the college admitted its first female student. You can walk all the way from Cambridge to Oxford without stepping off college land. We are not here for any of that; we are here for a seminar.

The college educated prominent abolitionists Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce, and today prides itself on its Slavery and Abolition Collection. The collection documents both sides of the slavery debate, pro and con—a useful correction to the self-congratulatory view of British history that celebrates abolition and turns a blind eye to everyone who defended slavery. This is what brings us to the Old Library: we are here for a class on abolitionism in the eighteenth century. My academic mentor Dr. Ruth Abbott is leading the session and I am taking notes because I will be teaching this class in the next academic year.

The archivist has prepared materials for the students: books, pamphlets, manuscripts. These are displayed on a large table that dominates the room. While she talks the students through the materials, I linger at the margins of the group. Space is limited, so I stay out of the way. While the others bend over a few illustrated pamphlets, my attention is drawn to a handwritten letter at the opposite end of the table. Having read tens if not hundreds of letters written to and from the Romantic poets, this looks very familiar. My interest is piqued. The handwriting is unusually neat, the paper well preserved, the ink unfaded—all hallmarks of good quality. My eyes run over the page. It turns out that this is a report written from the manager of a plantation in Jamaica to the plantation’s owner in Britain. It lists activities in recent months: building a shed, a fence, a change of crops. Something about cattle.

[Wordsworth’s] teacup and the plantation papers are not just randomly connected by the coincidence of my seeing them on the same day. In fact, they are two relics of the same history.

And then a remark about purchasing a group of men and women. Suddenly it sinks in. This letter was written from a plantation. This piece of paper had once been on a plantation. It might have been delivered to the post office by an enslaved Black person. But, worst of all, the hand that wrote out these neat sentences was soaked in the blood of Black people. The cruelty of plantation managers was notorious. The thought that one of them would have sat down at his desk to carefully pen this report to his employer in Britain and that his handiwork is now before me makes my head reel. Bile rises in my throat; my knees are ready to fold. I step back and bump into the archivist’s counter. About chest-height, made of chipboard clad in pale, imitation birchwood laminate, it is mundane, ugly, and can take my weight without creaking when I lean on it. Its office-like blandness is exactly what I need to pull myself into the present. I run my hand along its smooth surface, studying the plastic grain.

It takes me a while to notice that the room has fallen silent. All eyes are on me. Expectant. Not because they have seen me wobble, but because someone has asked a question that they expect me to answer. I have no idea what they’re on about. I wonder why they are asking me rather than Ruth, who is, after all, teaching this class. In fact, I do not wonder, I know why they ask me. It is not the first time that people have assumed that I am an expert on all things slavery just because I am Black. Of course, I am the only Black person in the room on this occasion, but this is precisely why I cannot answer or even hear their question just now. I say something in reply. I can no longer recall what it was.

Wordsworth famously defined poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” that “takes its origin from emotion recalled in tranquillity.” Memory is important here. It is not about feeling grand emotions and noting them down in real time. Rather, poetry is the ability to calmly sit down and recall what you once felt—and in so doing, the tranquillity disappears and you feel the emotion again. This is the guiding principle of Wordsworth’s own poetry. His major poems are all autobiographic. His great work, The Prelude, is an epic on “the growth of the poet’s mind,” according to its subtitle. Over fourteen books that he repeatedly revised over a period of fifty years, Wordsworth excavated his biography to explain how he became the poet that he was—the unstated assumption being that he was a paragon for the Poet as such. John Keats denoted Wordsworth’s poetical attitude as the “egotistical sublime.” The remark is rather snarky, but I must confess that I agree. To be honest, I have always found Wordsworth’s poetry a bit tedious. This self-important aging fart, going on and on about himself, his thoughts, feelings, emotions. Not my thing.

But the process of writing this book has taught me to read Wordsworth differently. His practice of recollection has some affinities with the concept of Sankofa, the going back to the past to get what needs to be remembered. No wonder I have often found myself recollecting in tranquillity on significant moments. Wordsworth called them “spots of time”—flashes of emotional intensity that unlock philosophical and political insights. The memory of that class at St. John’s comes to the surface when I sit down to recall my first encounter with Wordsworth’s teacup, which was resting in a display cabinet in the room next door.

Wordsworth was also once a student at St. John’s, and in the spring that we visited the Old Library, the college was hosting an exhibition celebrating his 250th birthday. The cases in the library exhibition displayed an impressive collection of Wordsworth’s manuscripts, early editions—and his breakfast crockery set. Seeing the teacup, I was immediately struck by the thought of the poet’s thin lips pursed against its rim and how drinking from it today would be akin to kissing Wordsworth across time. But class was starting, and I did not have time to dally. I formed an intention to stay behind afterwards to take a closer look at the exhibition, but at the end of the seminar I was just happy to get the hell out of there.

When I sit down to write about Wordsworth’s teacup a few years later, I realize that my recollection of it is tinged with the shock I felt in front of that slave plantation letter. It came from a set of papers related to a number of plantations on Jamaica owned by the Perrin family; the bulk of them are letters from various plantation managers to a man named William Philip Perrin. They stretch from the inventory made on his inheriting five plantations from his father in 1759, until his own death in 1820. During this time, a period spanning six decades, several generations of enslaved people labored on the Perrin plantations, working around the clock to enhance his fortune. From sunrise to sunset, the sugar cane fields needed attending: sowing, watering, weeding and harvesting. Backbreaking labour under the tropical sun.

Sugar is made from the juice squeezed from sugar cane. The juice needs to be processed immediately after the cane is cut; otherwise it will ferment and spoil. Therefore, sugar plantations also included a mill where the freshly cut cane could be processed. First it was passed through large wooden or metal rollers in which the cane was crushed so as to squeeze out all the juice. The liquid was then transferred to the boiling house. Here, the sugar cane juice would be heated to extract the sugar. To this end, the boiling house was furnished with a series of large vats, called “coppers,” each constantly kept at boiling temperature. As water evaporated, the juice was ladled from vat to vat, progressively reducing until a thick, viscous syrup remained. This finally was poured into barrels, known as “hogsheads,” or into conical moulds, which were put aside in the “curing house” where the remaining liquid would drain off. The drained liquid—molasses—was used for making rum, while the hogshead or mould would now be full of crystallized brown sugar ready to be shipped to Britain, where it would potentially be further refined to make white sugar.

The need for speed in processing the cane before the juice fermented, combined with the period’s inefficient technology and planter greed, meant that the mills and boiling house were operating throughout the night in harvest season. Working in shifts doing monotonous labour in suffocating heat, while also being malnourished and in pain, created its own danger: letting your attention slip for a second might mean getting pulled into the mill-rollers (this was so common that a dedicated worker would stand with a machete next to the rollers, ready to chop off any limb that might get caught). Losing your balance while maneuvering a heavy ladle full of boiling sugar juice could lead to serious burns; in the worst case, slipping and falling into a copper would mean being boiled alive.

A slave plantation was a lethal place not only because of the violence—the planter’s whip ripping into flesh, or the brutal punishments meted out for any act that might have been construed as disobedience—but also because the sugar mills themselves were death traps. Thinking of the generations of people who worked on the Perrin estate, it is particularly galling to learn that Perrin himself never set foot in Jamaica. All he knew—all he wanted to know—about life on his plantations came from letters like these: neat, well written, professional. The tone is efficient and business-like: details about hogsheads, crop rotations and bills of lading cover over a bloody reality merely hinted at in passing references to rebellion, illness and punishments among the enslaved workers.

Perrin’s absenteeism was typical for his time. If the early days of Caribbean sugar planting required a would-be planter to work on site to build up his estate, by the end of the eighteenth century many plantations were well established and their owners had taken off to lead a life of luxury in Britain, leaving the day-to-day management to agents. Meanwhile, these absentee planters used their money to influence parliament in their favor. In addition to postponing abolition, the West India Interest secured a favorable monopoly on sugar imports. As a result, virtually all the sugar consumed in Britain originated in the British West Indies.

Wordsworth may well have stirred some of the sugar whose production is described in the letters to Perrin—or in letters just like them, written to other absentee planters—into his tea. His teacup and the plantation papers are not just randomly connected by the coincidence of my seeing them on the same day. In fact, they are two relics of the same history. While I had been drawn to the cup by the thought that Wordsworth had once drunk from it, it is actually part of a much larger story about how foreign delicacies such as tea, sugar, coffee and hot chocolate entered British mouths. In the course of a few centuries, these products went from luxuries for the rich to everyday necessities for the working class: this process was underpinned by the establishment of a global economy along which foodstuffs, and the people who produced them, circulated.

Sidney W. Mintz has studied this transition with regards to sugar. The sugar cane plant originated in New Guinea, where it has been cultivated for thousands of years, though the first references to processed sugar are found in Indian literature from the fourth century BCE. Sugar slowly made its way westwards and was brought into Europe by the Arab caliphates who ruled the southern parts of the continent from the eighth century onwards. They began to cultivate sugar cane in Sicily, Cyprus, Malta and Spain, as well as Egypt and Morocco. Such sugar reached England in very small quantities, being so expensive that it was barely even eaten. Instead, it was used as a medicinal electuary; in one recipe, sugar was mixed with ground pearls and diamonds as a cure for bad eyes. Of course, only the very richest people could afford such medicines.

Sugar was also used to prepare subtleties—edible sculptures made out of marzipan. To make a subtlety, sugar and ground almonds were mixed with oils and vegetable gum to create a paste that was then shaped into different forms: animals, buildings, coats of arms. Pompously brought out between the main courses in early modern royal and aristocratic households, these dishes—quaintly spelled “sutelte” or “sotyltie” in the menus that Mintz has uncovered—were eaten, but their primary purpose was to display the host’s wealth. This made sugar desirable for anyone with social aspirations. More importantly, this shift in usage—from sugar as an ingredient in medicine to forming the base of a dish in its own right—introduced sweet courses into the choreography of fine dining: the first subtleties could come at any point in the meal, but over time they settled at the end, still present in the sweet dessert that comes last.

But sugar was not only used in desserts; importantly it was used to sweeten drinks that were introduced into European diets around the same time: tea from Asia, coffee from Africa, chocolate from the Americas. They were all brought back by the European explorers who had set out to “discover” the world. While their original uses influenced how the new imports were consumed in Europe, it is interesting to note that neither tea, nor coffee, nor chocolate had been sweetened in their original cultural contexts. It was Europeans who needed a sugar hit to soften the bitterness of these foreign beverages.

The high prices fetched for imported luxuries created a financial incentive for establishing overseas colonies: places with a favorable climate to grow exotic produce. The colonies also offered opportunities for agricultural experimentation, as planters sought to identify the most profitable way of extracting value from the land. Ecologically diverse, ancient tropical forests were cleared to establish plantations producing a single crop. This monoculture was a disaster for the environment, but it led to an explosion in production, which in turn led to increased imports and, over time, lowered prices. And as prices fell, sugar migrated down the social hierarchy so that, by the middle of the eighteenth century, it had become a daily necessity in any respectable English household (one may recall Coleridge’s complaint about the price of sugar in his first letter from university). A century later, sugar was a staple in even the poorest person’s diet: a tea break—including a cup of tea with milk and sugar—provided the calorie boost needed to get a British factory worker or miner through the day.

Caribbean sugar production depended on enslaved African labor, and the two—white sugar and Black bodies—became intertwined in the public imagination.

Sugar was one key reason why the British sought to establish colonies in the Caribbean. The initial plan was to use the Indigenous Taino population to work the fields, but this population was quickly decimated by genocidal conquest, ruthless working conditions as well as novel diseases brought by the Europeans. Attempts were also made to bring indentured laborers from Europe, who could pay for their passage across the Atlantic by binding themselves to work for a set period of time. When that period expired, they would be free to start building a new life on their own. Other Europeans arrived as political exiles or refugees—for example, there was a Jewish minority who had decided to emigrate to escape antisemitism in Europe.

But Caribbean sugar production only got underway on a large scale with the arrival of enslaved Africans; a model first tried by the Portuguese in the Cape Verde and Canary Islands. Although mortality among the African laborers was catastrophic, incipient racism encouraged the planters to devalue Black life; these deaths were not manslaughter but a problem of accounting, of how to calculate risks and returns on investment—”a racial calculus and a political arithmetic,” to use Saidiya Hartman’s designation of this conversion of persons into numbers.

This means that Caribbean sugar production depended on enslaved African labor, and the two—white sugar and Black bodies—became intertwined in the public imagination. The association was weaponized by the abolitionist movement. In addition to convincing people of the moral wrongs of enslavement, abolitionists pioneered the use of consumer boycotts as a tool of political activism. Their aim was to strike at the profitability of the slave economy by making people abstain from sugar and rum—the two most important slave-produced imports from the West Indies. To this end, campaigners forged an equivalence between taking sugar and drinking human blood. “A part of that Food among most of you is sweetened with the Blood of the Murdered,” Coleridge railed in his Slave Trade lecture of 1795. His denunciation of sweet things as “the Food of Cannibals” was firmly in line with contemporary abolitionist talking points. Benjamin Flower, one of Coleridge’s Cambridge associates, ridiculed refined ladies who “sweeten their tea, and the tea of their families and visitors, with the blood of their fellow creatures,” while William Fox carefully calculated that “every pound of sugar” was equivalent to “two ounces of human flesh.”

This metaphor also entered visual culture. James Gillray’s 1791 satirical print “Barbarities in the West Indias,” for example, represents a sugar-boiling copper as a giant teacup into which a cruel-looking white overseer stirs a Black man like a human spoonful of sugar. Literary historian Deirdre Coleman notes that the image “literalizes the metaphor of sugar-eating Europeans ingesting African flesh and blood. The drowning African melts in the huge cauldron of boiling sugar juice; he or she passes invisibly but materially into the substance of refined white sugar, which then circulates around the tea-tables of the West.” The violence of the plantation was such that blood inevitably got mixed up with the sugar cane juice, but Coleman’s analysis of 1790s abolitionist imagery also identifies a symbolic iconography at work. Consuming sugar brought white digestive systems into dangerous proximity to the Black hands that grew, cut and processed the sugar cane. The cannibalistic tropes point towards fears of racial contamination—the uncanny possibility that white consumers might ingest residues of Blackness along with the addictively sweet granules.

__________________________________

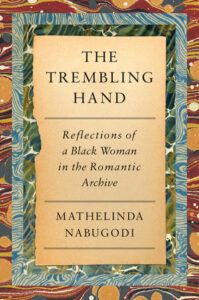

From The Trembling Hand: Reflections of a Black Woman in the Romantic Archive by Mathelinda Nabugodi. Copyright © 2025 by Mathelinda Nabugodi. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Mathelinda Nabugodi

Mathelinda Nabugodi is a Lecturer in Comparative Literature at University College London. She has previously held post-doctoral fellowships at Cambridge and Newcastle, including in the literary archive at the Fitzwilliam Museum. She is the author of Shelley with Benjamin: A Critical Mosaic (2023) and one of the editors on the six-volume Longman edition of The Poems of Shelley (1989-2024). Her current research explores the connections between British Romanticism and the Black Atlantic.