When our marriage ended, I told Seth it was because we had too many White People conversations. He pretended not to know what that meant—“But we are white, Cynthia, we happen to be white”—but I knew he did. To drive the point home, I read aloud the last string of texts we’d exchanged: Pea soup for dinner? / NO too wintry. / Asparagus then? / Asparagus is overplayed. / Well you stop by Chelsea Market yourself and see what you’d prefer to eat, Seth. We’re even fighting like white people, I said, and again Seth protested anemically that white people don’t fight any differently from other people. But we both knew they do. White people fight in very low voices, in public, while smiling. My parents did it. His parents did it. And this was something I didn’t want to do anymore.

*

When I met Elias, I knew that he was the kind of man that Seth would feel threatened by, but I wouldn’t say that was what made me like him. I think we had a real connection, and if Elias happened to be Venezuelan, if he happened to have tattoos up the corded muscle of his right arm, if he happened to be a modern dancer who specialized in a “physical and metaphysical silent dialogue about race” (his words), well those things were just points of interest over which we connected. Points of interest that Seth and I had unfortunately never shared.

“I didn’t know you had any interest in modern dance,” Seth said pointedly over what we were calling a Divorce Dinner. We were having Divorce Dinners once a week, to amicably discuss how to be amicable, and also to divvy up shared possessions—who wanted the record player, who needed the hooked rug from Morocco, who got to keep which friends. It was at one of these Divorce Dinners that Seth told me he’d started seeing a twenty-one-year-old Women’s Studies major at Barnard named Macey. I ground some pepper in a light sprinkle over my hand-raised quail, and then expressed that I was very happy for him, that I had myself actually almost been a Women’s Studies major, although quite possibly he didn’t know that about me despite our six-year marriage, and that I had, myself, started “seeing” a twenty-seven-year-old Venezuelan modern dancer named Elias.

Seth didn’t sprinkle pepper over his own hand-raised quail. He just stared across the restaurant table at me, his blue eyes narrow. And then he questioned my interest in modern dance. I expressed to him that I quite liked modern dance, that Merce Cunningham was very inspirational for me, and that I had once read the biography of a German modern dancer whose name I couldn’t, in the moment, recall. Seth expressed that he thought my interest in modern dance was a crock of shit. I expressed that I thought Seth was an asshole with a tiny flaccid cock. We ate our mutual hand-raised quail silently, with ferocity, for a few minutes. Then Seth pointed out that I did not seem like myself. That kind of crass language was childish, and I was actually a very rational and mature person, with whom he could usually have rational and mature conversations, and this whole thing wasn’t like me at all.

No, I said, it isn’t. And that felt good. To be unlike myself. So then I ordered dessert.

*

When I told Elias that I was still married but in the process of extricating myself, he just said, “Oh,” and kept stretching. He was developing what he called a “portfolio of gestures” for his upcoming dance-meditation at Judson Church, and I was trying to help. Watching Elias work inspired me. It made me imagine the life I could have had, if I hadn’t married Seth, in which I wore paint-spattered denim and had two full tattoo-sleeves, and also muscles, and also a portfolio of my own gestures that people wanted to watch me perform.

I asked if Elias had any feelings or questions about Seth, but he just looked at me a little oddly, said “No,” and kept stretching. Seth would have had a lot of questions. Seth would have wanted to measure himself against this other guy and make sure that he was better in some way. Elias’s quiet confidence and lack of curiosity were almost as inspiring to me as his portfolio of gestures. And then it occurred to me: passive jealous probing wasn’t in his cultural heritage. That was a white thing, and Elias was Venezuelan. I wanted to tell Elias how grateful I was to be able to learn from him, but he’d already turned his back on me.

The first set of gestures in his portfolio involved tucking one foot behind his knee and tilting, without falling. Every time he appeared about to fall, he would take a tiny hop, and rebalance himself. If you thought about this as a political metaphor, it was clearly about self-rescue, and not waiting for a higher power to step in. I started to imagine Elias as a small boy in Venezuela. We’d never discussed his past, which I assumed meant that it must have been a hard one. I imagined him barefoot, walking along a dirt road. Goats somewhere, grazing off meager grass, their small noses brushing chewed-bare earth. Elias, mouth dry, liquid brown eyes squinting into an unforgiving sun. Where was his mother? Maybe a nanny, already in the U.S., maybe working to send money back to his grandmother who was looking after all of her children. Motherless and neglected, Elias would wander out into nature and spend hours communing with the wind and the sun, the soil beneath his bare feet. No wonder he spoke so little. No wonder he needed nothing from anyone. He’d brought himself up this way, as his only alternative to privation.

I found that my eyes were full of tears. I brushed them away, before Elias turned back around. Hop-tilt-hop. Hop-tilt-hop. He never fell, and he never turned around.

__________________________________

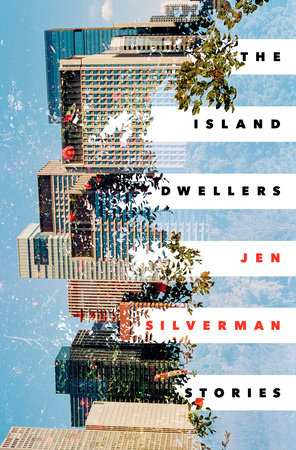

From The Island Dwellers. Used with permission of Random House. Copyright © 2018 by Jen Silverman.