Railroaded by Luminescence

As an illustration of what I was up against at Napa State Hospital, what they used to call an asylum for the criminally insane, my fellow inmate Arn Boothby, an angry three-hundred-pound paranoid schizophrenic who regularly “cheeked” his meds, tried to kill another inmate one day in the client convenience store by grabbing his throat and throwing him through a glass display case. I was standing in line to buy a pack of breath mints at the time and can attest to him saying, “P. S. I Love You,” as the blood spread across the tiles. Boothby was tackled by two psych techs; a staff nurse and hospital police converged within minutes to beat in Boothby’s brains behind closed doors. Boothby told me later they would’ve killed him had not Dr. Fasstink inadvertently intervened. Boothby went to jail, vacation time for most of us at NSH, and I didn’t see him at the card game for a few months. When you’re surrounded by murderers, bank robbers, arsonists, and child molesters you’ll play cards with just about anyone.

And I know what you’re thinking (I really do): that I’m innocent, that I don’t belong here. Every inmate says this. Well, I’m not innocent, but I should’ve never been sentenced to a high-security psychiatric hospital full of overmedicated, violent maniacs when I had done nothing but shoplift and make a few crude remarks to women in bars, ride twenty-five-thousand miles on an imaginary bicycle, fancy that I was the ruler of the universe, and run a few delusional undercover operations for the CIA, all brought to you by not taking my meds—or so it was explained to me. I think it was the pattern more than the nature of the violations, and the fact that I had left the halfway house before the expiration of my term, that swayed the judge. Whatever the case, I was mandated by court order to an indefinite term at NSH, and once you’re in one of these places you’re pretty much at the mercy of the people who run the show.

I did myself no favors at Napa State, for I was outraged to have been placed in a community rife with the worst kinds of con artists, malingerers, and career criminals who’d pled insanity to avoid life sentences in a penitentiary. Then there were the genuinely insane inmates, not a minor case among them, all wandering around freely to do whatever they liked to whomever they pleased. Half the inmate population had killed or tried to kill someone. All the barbers were murderers. One of the barbers, my close friend and first choice for a haircut, Randy Sturtz, had killed his brother and then a neighbor over a cinnamon roll. Cecil Jebb, my roommate for six months, had raped a woman and then tried to strangle her in the parking lot of an Oakland shopping mall, the only time, he liked to brag, that he’d ever been caught. Darvan Laval, a dining companion of mine many evenings who loved to fight, had killed a schoolmate when he was fifteen.

Most of the staffers were unarmed women who could not handle the larger, more dangerous male criminals and often had to resort to calling the police. It was no coincidence that about every three months a troublesome inmate would die after a mysterious reaction to an injection or a scuffle with the cops, always behind closed doors.

I was even more outraged at getting thrown into a unit with sexual predators. And since I wasn’t, had never been, and would never be a sexual predator, I refused on principle to take the class on sexual harassment, my only official prerequisite besides good behavior for getting released. I also refused the voluntary work. I’d been a journalist in the free world (I had moved from San Diego for a job at the San Francisco Chronicle, where I was given the Bay Meadows/Golden Gate beat and my own weekly horseracing column) and I was not about to descend to menial labor in the vulnerable company of barbarous psychopaths. In the first few months I was there a psych tech was murdered by an inmate, the whole hospital went into lockdown. And, though it was always us versus them and this was a good chance for me to be left alone in my room and listen to the radio, many of the staffers took out their fears and frustrations on us, withholding privileges and invoking arbitrary punitive measures, as if we had all conspired to kill their comrade and needed to be taught a lesson. I often felt like that character in the movie Shock Corridor, the undercover reporter who commits himself to a mental institution to solve a murder, gets caught up in a riot, receives shock treatment, goes berserk, and never sees the free world again.

At twenty-seven years old I was not emotionally equipped for living under lock and key behind sixteen-foot cyclone fences and having my ass stabbed every three days with drugs that turned my brains to buttermilk. Not only was I bipolar (my original diagnosis, eventually changed to schizophrenia) and prone to dramatic mood swings, I was angry, lazy, selfish, contrary, immature, arrogant, headstrong, and a lover of pranks. I thought I was important because I had invented the now widely used track classification system that distinguishes primodrome, mezzodrome, and llamadrome, or high, middle, and cheap purse tracks. In case you are not acquainted with horseracing, the system is called the “Plum Variable” or simply “the Plum,” as Andrew Beyer’s homologous speed figures have simply become “the Beyer.” I had also come from a somewhat prestigious family. My father, Calvin Plum, was the notable southern California horse trainer who’d won both the Santa Anita Derby and the Del Mar Futurity twice, and who had also at one time been the largest grower of poinsettias in the world. One of his wives, my third stepmother, had been married to the legendary songwriter Burt Bacharach.

“The fact that I was one of the few inmates who hadn’t committed a felony (I still had the right to vote!) must have nagged the one or two administrators who cared.”

Looking back, it almost seems as if it were my sole mission to never grow up so as to prolong my stay at Napa State indefinitely. Though never a fighter before my commitment, I had to become one to survive, especially when someone tried to play grab-ass with me in the showers (the ones who came at you low you had to get around the neck and the ones who stood their ground you could run into walls with your head and drop them before the attendants came running). I organized the first decent lottery the hospital had seen in years, did not resist the black market (though I stayed away from illegal drugs), participated in numerous tobacco-for-sex arrangements, Vaselined the underwear of my rivals, hosted weekly poker games, invented tranquilizer bingo, and palled up with the killers and fighters so they wouldn’t kill or fight me.

In spite of all my shenanigans and refusal to take the harassment class, due to overcrowding, budget and staff cuts, and a long waiting list to get in, the hospital was prepared to release me. The fact that I was one of the few inmates who hadn’t committed a felony (I still had the right to vote!) must have nagged the one or two administrators who cared. But then came the incident with Morris, the unit supervisor who was putting the watusi on one of my tobacco girls. He warned me to stop seeing her. I told him in so many words to cram it, so he blew the whistle on me. Half the people in the hospital exchanged tobacco or money for sex, and since we weren’t saints but lunatics with needs like all human beings, the hospital usually looked the other way.

But Morris and I didn’t get along. I was constantly switching his nametag with those of female attendants (for two hours one day to the giggling of dozens he was “Amy Ocampo. Staff Nurse”), and whenever I could I would glue his pens together. And he needed to deflect attention from his own multifarious misdeeds (including the homebrew he sold black market and the female clients he took home on weekend passes) so he hit me with “sexual aggression,” a label that goes a long way against anyone who’s already been tagged a sexual predator. Then a mysterious “second party” informed my shrink, Dr. Fasstink, that I was having sex for money with Tasha Little, the thirty-four-year-old mulatto girl on T-17. They had a mini-team on the case and declared that I was “wheeling and dealing.” Wheeling and dealing is commendable in free society, but at Napa State it set me back one release hearing at least. Dr. Fasstink, a dainty Latvian with limp wrists and a close-cropped Freudian beard, increased my Haldol from 100 to 125 mg. A few weeks later, Tasha left me for a forty-seven-year-old Cuban fruitcake called Rey Waldo Diaz.

In many cases the staffers, administrators, and psychiatrists were crazier, crueler, and more criminal than the bedlamites they reputedly supervised (note here for the record that Claude Foulk, the director of Napa State, was recently sentenced to 248 years for raping children all the way back to 1965). Napa State was plagued with one sex scandal, drug ring, and unjustifiable death after the next. It was a classic case of the inmates running the asylum, King of Hearts without the laughs. And Morris, just to protect his harem and be a hardass and get revenge on me for putting sneezing powder in his Kleenex, placing ads for him in various Bay Area singles’ and swingers’ papers (“I’m a pink vinyl and diaper-rash ointment kind of guy”), and pouring pancake syrup into his shoes, would bust me for anything—dealing coffee, breaking curfew, playing craps, or changing the channel on the TV without authorization.

Just before my second hearing for release came up, Morris got me kicked off Unit T-15 after I’d told the recreational therapist why I was still at Napa when I could have left long ago. I told her I’d had sex with a hundred female inmates, sometimes two at a time. Her recreational title had misled me and I thought she might be impressed or at least take my elaborate boast in the “recreational” spirit in which it was intended. I certainly didn’t think she’d tell Morris, but it turned out they were makin’ bacon (in his office) and so when he heard the news he told Fasstink and all of a sudden I was a “problem patient,” an “operator,” and though my various infractions amounted to little more than mischief they somehow through the Constitution of Lunacy qualified me as a “repeat offender” and justified my continued confinement without counsel or trial. For a long time I had my father, the prominent southern California circuit horse trainer, hiring attorneys to get me out, but once he learned that all I had needed from the beginning for a release from Napa State was to take a sexual harassment class he washed his hands of me. The larger point was forgotten, that I had done basically nothing to be sent and kept here indefinitely against my will.

__________________________________

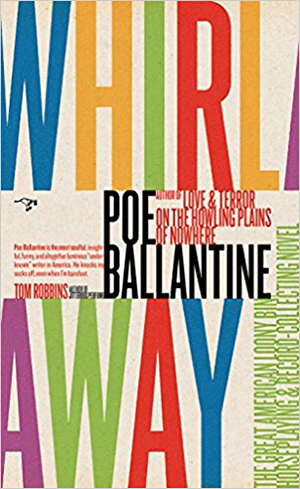

From Whirlaway: The Great American Loony Bin, Horseplaying, & Record-collecting Novel. Used with permission of Hawthorne Books. Copyright © 2018 by Poe Ballantine.