Wherever You Go, There You Are: On Setting and Society in Pride and Prejuduce

C.K. Chau Considers the Impact of Place in Jane Austen’s Classic

In Pride & Prejudice, neighborhood comes first—literally. It’s the first character introduced, the establishing shot for the world that Austen creates, and the defining order of the relations within it. We, along with the Netherfield players, join the story by moving into it.

“Place” in Pride and Prejudice isn’t set dressing, but an ecosystem of social bonds, individual relationships, and physical space. It refers to both the diffuse network of individuals within a specific territory (what Austen might call “society”), and the physical sites themselves (which can offer reprieve from that same society). To be seen in society is to be seen by society, and accordingly read and fixed into one’s rightful (social) place. But social bodies are never still. As characters move between “places” and disjoin from their known society, their perceived character destabilizes, creating possibilities for reassessment and reconciliation, enough to make themselves legible to and by each other.

Austen’s representation of space is highly personal. Character is wedded to geography from the start. When Bingley removes from Netherfield to fetch the rest of his party, Mrs. Bennet reads in it the possibility “that he might always be flying about from one place to another, and never settled.” Darcy’s behavior at the ball sets him as “above his company” and apart from the others in the neighborhood, who then pronounce “his character…decided. He was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world, and everybody hoped that he would never come there again.”

By contrast, Wickham seeks to immediately establish himself as a neighbor, “speaking of the [society] especially, with gentle but very intelligible gallantry.” What makes a body likable and “intelligible” is the ability to be read and absorbed into the community. Bingley and Wickham play ball; Darcy, resolute in his character, refuses, and so is maligned and condemned to stand outside it.

For Darcy, the country presents a “very confined and unvarying society,” one defined by its wildness and lack of conformity to social decorum. When Caroline criticizes Elizabeth for walking to Netherfield, she finds it “an abominable sort of conceited independence” that shows a “most country-town indifference to decorum.” Caroline’s observation marries personal character with kept society; Lizzie’s “conceited independence” isn’t accidental, but a direct reflection of the values and environment of her place.

To be seen in society is to be seen by society.

Compare this to the descriptions of “town” as a site of “eminence” and education, marked by “superior society.” Read within their spatial contexts, Lizzie and Darcy are immediately set at odds, made illegible and unlikable to each other through that difference.

To be seen within society is to suffer interpretation. Only absence or removal allows for disruption of an assumed continuity of character. Bingley may occupy a favored position early in the novel, but his later removal to London breaks the perception of his character. The “amiable qualities” that define him become “thoughtlessness, [and] want of attention to other people’s feelings.”

For Lizzie and Darcy, whose personal characters are so strongly rooted in place, their relationship only benefits from removal. Away from the Bennets and the Netherfield party, their dynamic recalibrates, represented through their clumsy configuration of new space. When Darcy undertakes a visit to Hunsford, he finds himself “astonished… on finding [Lizzie] alone, and apologized for his intrusion.” The intrusion isn’t only his. Hunsford is an unfamiliar space for both parties, and it’s the “intrusive” nature of their presence that allows them to engage on new discursive terrain.

As they converse, Darcy’s attention to decorum and formality visibly slacken. He “[draws] his chair…towards her” and says, “You cannot have a right to such very strong local attachment. You cannot have been always at Longbourn.” His increasing admiration and feeling for Elizabeth culminates in an interjection that divorces her from her society, literally setting her apart. His visible emotional turn also breaks Lizzie’s reading of his character up to that point.

She observes he “experienced some change of feeling,” before he retreats to the safety of the usual script, drawing back his chair to solicit “in a colder voice” her opinions of Kent. A disruptive burst of physical proximity that gestures towards new intimacy must be corralled and contained; we return not just to small talk, but to reminders of where we are in space. But a new pathway has opened, one that allows for the possibilities of revision and personal change.

During their time in Kent, Darcy and Lizzie continue to encounter one another in spaces where others are absent. Elizabeth takes it poorly, feeling “all the perverseness of the mischance that should bring him where no one else was brought” and calling it “wilfull ill nature, or a voluntary penance.” Darcy’s run-ins aren’t just bad luck; it’s unnatural, both in its “perverseness” and in its violation of her understanding of him. It also marks the initial point of departure between the wider social consensus around Darcy’s character and her own, a divergence that will only grow. Hunsford gives Elizabeth room to articulate her interiority for the first time, as William Deresiewicz has observed, opening a door to personal individuation from the uniformity of her larger society.

Her appearance at Pemberley offers similar reckoning. Following the catastrophic proposal, Elizabeth’s new hyperawareness of their social geography leads her to reinforce their bounds. She concedes her trespass into “his county with impunity” (emphasis mine) with the allowance that it passes “without his perceiving [her].” Yet any review of the terrain also reopens review of his character. She finds the Pemberley grounds to be “neither formal nor falsely adorned” and “little counteracted by an awkward taste,” descriptions previously levied against its owner.

Out of her element and fully enclosed within Darcy’s territory, Elizabeth maps her understanding of him onto the land itself. She not only tours the grounds, but “turned back to look again” as they prepare to leave. In an inversion of the myth, the Orphic look back restores the possibility of romantic resolution. She looks back and sees him—fully realized for the first time, independent of the prevailing criticisms of society.

Displaced from their usual social environs, awkwardness and uncertainty overwhelm their reunion. Neither knows where to look, what to say, or how to act. He lacks “perfect composure,” but manages to recover; struck with surprise, Elizabeth “scarcely dared lift her eyes to his face” and later acknowledges being overcome “by shame and vexation.”

This mutual discomfort grants them equal footing, relationally and emotionally. At their next meeting, Elizabeth discovers “all that [Darcy] said [had] an accent so far removed from hauteur or disdain…as convinced her that the improvement of manners, which she had yesterday witnessed, however temporary…had at least outlived one day.” The disruptive power of their earlier interactions bear fruit in the softening of her judgment.

We begin by arriving into the neighborhood, and we end by leaving it. Secure in their newfound understanding of themselves and each other, Lizzie and Darcy seal their happy ending with a leaving-home, “look[ing] forward with delight…when they should be removed from society so little pleasing to either, to all the comfort and elegance of their family party.” They abandon the limiting societies they’ve suffered in favor of a “place” of their own—one joined of the best of their families, reflective of their personalities, and conducive to their joy.

__________________________________

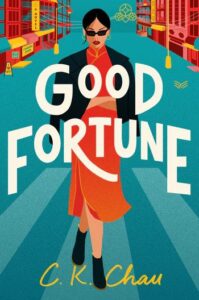

Good Fortune by C.K. Chau is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

C.K. Chau

C.K. Chau is a Chinese American writer based out of New York. Her writing has appeared in Bright Wall/Dark Room, among others, under another name. A graduate of Hunter College, she currently works in publishing in New York City.