“Where You From?“ The Problem With Shortcuts in Writing Place in Fiction

Brett Biebel on the Role of Geography in Creating Character

“Where you from?” someone will ask, and I might give them one of a dozen different answers. Minnesota, maybe. Or Wisconsin. Iowa. Recently I’ve settled on something like, “Oh, you know, just generally around the Midwest,” but none of these ever feels quite right, probably because there seems to be so much riding on the answer.

That “Where you from?” is often the first question we ask each other upon meeting, and for good reason. Geography stands in for a whole set of associations about politics, language, culture, etiquette, and even personal qualities (think laid-back left-coasters, brusque and direct New Yorkers, and “bless your heart” Southerners), and fiction often grapples with this—with the role of place in creating identity. In my experience, however, film and literature tend to underestimate the role of geography in our lives, relying on shortcuts and stereotypes, and, in the process, failing to accurately depict its importance, even in globalized life.

As someone who writes a lot about a lot about the Midwest, I see fiction’s reliance on shortcuts most often in relation to rural settings. There’s a moment in the third season of Hulu’s Shrill, for example, where the main character is driving out of Portland to conduct an interview. The signifier for her exit from the city is a billboard featuring a rifle and the tagline, “We Don’t Call 9-1-1.” In the first episode of Friday Night Lights, an elementary school student stands up and earnestly asks the star quarterback of the beloved high school football team, “Does God love football?” and the score swells in the background.

On some level, both of these examples make sense. As a compressed medium, film relies on shorthand images to create powerful associations, and there’s truth here. I’ve seen countless billboards like the one in Shrill and certainly encountered the strain of the earnestly forceful Christianity depicted in Friday Night Lights. Still, there’s a heavy-handed simplicity to these examples, and even though literature is a linguistic medium rather than a visual one, it often indulges in that same simplicity.

The most compelling recent instance of this may be Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, a novel that takes place largely online, with its narrator inhabiting various international cities almost symbolically, only barely physically present, giving lectures about internet life in conference rooms and staying at hotels that could exist anywhere. The emotional heart of the book, though, is set in a hospital in Ohio, where the narrator’s sister is attempting to cope with a high-risk pregnancy. That Ohio setting is made clear largely through references to state politics, abortion in particular, and the pre-existing associations the reader will attach to red-state policies. The reader, then, is asked to see Ohio not as a place, somewhere people actually live, but as a symbol, as representative of a strain of thought that feeds into the book’s major themes.

In part, this is why I find Lockwood’s book so fascinating; it can be said to have no physical setting, to take place primarily in the interplay between the virtual world and the narrator’s mind. The book may even be arguing that geography doesn’t matter as much as my own opening paragraph claims—that the internet has become a flattening force, allowing us to form identities and relationships separate from the limits of physical space. Still, I worry about the use of geographic shorthand in fiction (and the increasing attention to the virtual world in modern storytelling) in part because physical geography is the driving force behind political polarization in the United States.

Increasingly, the phenomenon of “self-sorting” is creating a situation where many of us live near people who think like us; we mark off parts of the map as “not us,” an othering process that exacerbates many of the rifts in American politics and culture. The geographic shorthand of fiction feeds into that process, encouraging our gut-level assumptions about the culture and values of specific parts of the map and thereby encouraging polarization. I’m after fiction that, instead, highlights geographic complexity, and, in so doing, does what literature does best: undermines dominant cultural narratives.

What does this look like? How does a writer create geographic complexity? It might start with simply thinking deeply about place. Google Maps offers the opportunity to walk through the streets of our stories, and writers are (rightfully) taking advantage of that, just as many writers continue to engage in more traditional kinds of geographic research (e.g. talking to locals, attempting to capture regional vocabularies and rhythms of speech). The reliance of our political discourse on microtargeted propaganda and the rise of various social “bubbles,” however, have made it very easy for writers to fall into geographic clichés.

One way to deepen fictional depictions of place is to be as aware of geographic clichés as we are of linguistic ones.Indeed, one way to deepen fictional depictions of place is to be as aware of geographic clichés as we are of linguistic ones, to avoid reaching for the easy setting signifier in the same way we work to avoid the usual plot contrivances or standard character archetypes. Maybe the trick is as simple as never letting the mind settle into “vacation” or “tourist” mode and always carrying a map, always looking for something that represents a place not as its public face, the billboard on the side of the highway, but in a tucked-away corner, something you can only find by really looking. It might be focusing on smaller settings—single towns, counties, states—or challenging the usual political symbols. For me, the most effective technique is to read with an awareness of geography, always being on alert for details or bits of dialogue that make me feel like I’m actually living in the narrative setting.

Over the years, I’ve found lots of examples of this geographic complexity. Willa Cather’s Nebraska stands out. So, too, does the Santa Teresa of Roberto Bolaño. In Cather’s case, it’s her focus on the dichotomy of the prairie, its ability to drive people into the worst kind of lonely darkness while also, somehow, bringing those who survive closer together. For Bolaño, as with the Baltimore of The Wire, it’s the writer’s ability to paint an institutional picture of the city—the drug trade, the police, and the exploitation that runs throughout the economy. Jim Gauer’s Novel Explosives uses the street design of Guanajuato as a kind of metaphor for the narrator’s confused identity, and the stream of consciousness in Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport returns, again and again, to the narrator’s childhood, to Connecticut and suburban Chicago, while also giving readers a deep picture of her current home in Eastern Ohio—its charms, divisions, and bloody history.

In all of these books, geography is not easily reducible. Indeed, it’s sprawling, complex, and filled with contradictions, and that feels like the antidote to impermeable borders and our drawing of binary maps. The writing feels like a kind of signal that people still live in unique places, that unique places somehow still exist.

Of course, even in these books, geography isn’t the only detail at the core of the story. But, reading them, I am able to get beyond the image of, say, Ciudad Juárez as primarily associated with the drug trade. I’m able to see Nebraska as more than just flyover country. I’m able to recognize the heterogeneity of an Eastern Ohio that, in my head, is usually colored deep, deep red. Looking forward, I’m imagining a kind of fiction where geography more commonly inhabits the center of the story—where the deep exploration of place becomes a standard expectation for novels and story collections. Maybe that’s the kind of writing that can change preconceptions and shatter information silos, and maybe it can better depict a world where ZIP codes tell us everything we need to know about money, healthcare, politics, education, and values. Everything except what you can only see if you’re really willing to look.

_______________________________________

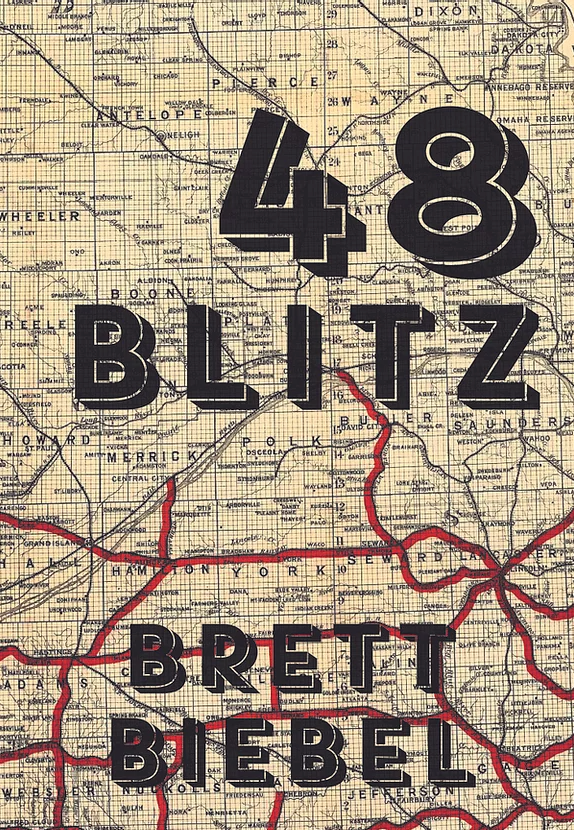

Brett Biebel’s 48 Blitz is available now from Split/Lip Press.