Where Words Dissolve: Yoko Tawada on Language as a Destabilizing Force

“I am searching for that state just before individual languages are dismantled—freed from their meanings and finally annihilated.”

I went to Marseille for ten days in the summer of 1999 on a sister-cities artist exchange program: each year, two to three artists from Marseille go to Hamburg and vice versa to read and translate each other’s work with the help of an interpreter. Joachim Helfer, a writer who came to Marseille with me, could speak French, but none of the writers in Marseille could speak German.

With the help of interpreters, we all worked together every day from morning to night huddled in a room in the library. Part of me wondered whether ten days wasn’t a bit much—I thought two or three might have been sufficient. But the organizer, a young woman who seemed quite passionate about her work, said the whole thing would be meaningless if the program were too short, so I surrendered myself to whatever plans she had.

In hindsight I am very glad I participated, as I got a lot out of it. It was there that I met Bernard Banoun, who later translated two of my books into French. Listening to a language I didn’t understand from sunup to sundown every day allowed me to experience a special state of mind I had never experienced before. I was paired with a young writer named Véronique Vassiliou, and speaking to her through an interpreter—listening to what she said, and then listening to the interpreter translate what I’d said to her—meant that I was listening to French for four hours a day, every day.

I expected that listening to French would be a waste of time, since I don’t speak it or understand it, but when actually in the conversation I found my whole body transformed into a giant ear. I couldn’t not listen, nor did I feel that listening was a waste of time. Instead, the sounds of the words, the gestures, body heat, and light made me feel strangely fulfilled. Everything was there except for the meaning of the words. When night fell, something unusual would happen. I’d have the strangest dreams—some of the strangest I’ve ever had in my life, almost as though I’d been drugged.

In my dream, a brightly-colored snake slithered languidly across the ground, and tree buds glistened in the sunlight. The green of the buds leapt over the boundary separating me, the observer, from the image being looked at, and began to extend inside of me. Moreover, it was absolutely clear to me in the dream that the snake and the buds were language itself. But that didn’t mean it was abstract. In my dream, this “language” was raw, so close to my body that it didn’t seem possible for it to be any closer.

My emotions lost their armor and garments and stood there completely naked. The slightest tremor in the air made me want to cry, scream, even kill. I had a premonition that if things continued this way, something terrible would happen. All distinction was lost between words and things, and my nerves were completely exposed. Is this the kind of world I’d secretly been seeking? It was terrifying, and at the same time, I had never experienced life so vividly. Perhaps at its core, language is merely a potent drug.

How much creative stimulation can we draw from the state of not understanding at all or from the state of still understanding only a little?

The day after the workshop, I gave a reading at a small theater in Marseille. The plan was for all of us to fly to Hamburg the following day to do a reading at the French Cultural Center. I spent the entire taxi ride into Hamburg talking with Joachim Helfer. The excitement of the workshop had not yet cooled. I was so engrossed in the conversation that I’d lost track of time, until I suddenly realized that the cabdriver was going down a strange road. It ought to have been a straight shot from the airport to the venue, but now he was turning right and left at every block, winding through residential areas at incredible speed like a city rat.

When I looked closely, I glimpsed a few buildings that seemed familiar, and we seemed to be going in the right direction overall. Why was the driver going to all this trouble when he could have just taken the main road? I saw him gritting his teeth. I realized then that he was angry—here we were on our high horses, talking about literary theory, completely ignoring him. This wasn’t the first time I’d experienced this. Most Japanese cab drivers are professionals, but many German cabdrivers are former teachers, poets or artists struggling to make ends meet. This driver probably heard us chatting away about literature to each other, arrogantly assuming he was just a driver who wouldn’t understand our conversation. But this town was his language, Hamburg’s roads a grammar only he understood. He continued weaving through the streets like a rat running through a maze, cutting corners as he raced on. I began to feel nauseous. I suddenly wanted to cry. I had finally made it home, only for this to happen. Wasn’t this just a continuation of losing myself in French?

Thinking about it later, I realized that I have never listened to a language I didn’t understand for as long as I did then. Thanks to this experience, French has come to occupy a position of “pure language” in my mind. Some might argue that if I’m going to spend so many hours listening to a language I don’t know, I may as well study it. But there’s something priceless about that state of unknowingness. I’m sure eventually I will study the language, but I want to savor this suspended state of unknowingness for a while. How much creative stimulation can we draw from the state of not understanding at all or from the state of still understanding only a little?

When I was first learning German, I was so desperate to learn it quickly that I never had time to actually observe things like this. But I think at this point in my life, to a certain extent I can surrender myself to the state of not being able to communicate. I can simply observe myself stumbling and falling without feeling too much shame about it. Once people are able to communicate, they do it all the time, without thinking. That’s all well and good of course, but language has a more mysterious power within it. Maybe what I am really searching for is a language that has been freed of meaning altogether. Perhaps the reason why I ventured outside of my mother tongue to begin with, and why I keep seeking a world where multiple cultures overlap, is because I am searching for that state just before individual languages are dismantled—freed from their meanings and finally annihilated.

__________________________________

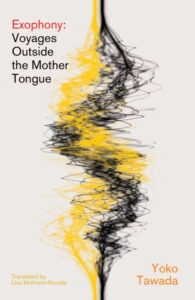

From Exophony: Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue by Yoko Tawada. Used with permission of the publisher, New Directions. Translation copyright © 2025 by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda.

Yoko Tawada

Yoko Tawada was born in Tokyo in 1960, moved to Hamburg when she was twenty-two, and then to Berlin in 2006. She writes in both Japanese and German, and has published several books—stories, novels, poems, plays, essays—in both languages. She has received numerous awards for her writing including the Akutagawa Prize, the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, the Kleist Prize, the Goethe Medal, and the National Book Award. New Directions publishes her story collections Where Europe Begins (with a Preface by Wim Wenders) and Facing the Bridge, as well her novels The Naked Eye, The Bridegroom Was a Dog, Memoirs of a Polar Bear, The Emissary, Scattered All over the Earth, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, Suggested in the Stars, and forthcoming in autumn 2025 is Archipelago of the Sun, the final novel in her Scattered trilogy.