Where Time and Space Collide: In Praise of Old Maps

James Cheshire on the Valuable Work of Preserving and Unearthing the Past

“Maps are funny things because they appear to be the reality, and yet they give you a tremendous opportunity to dream.”

–Peter Barber

*Article continues after advertisement

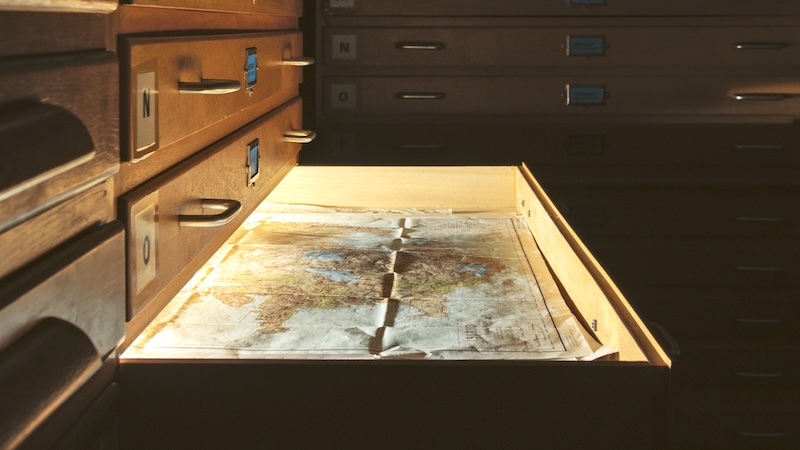

Not long into my searches of the Map Library I grew impatient to make discoveries and weary of clambering up and down the tall yellow stepladder I needed to reach the drawers that towered above my head. To speed things up, I developed the technique of pulling out wodges of maps and then jumping from the ladder, holding the weight of maps as best I could. A few would flutter out of my hands as they caught the breeze of the freefall, while the rest landed on an adjacent table just as my feet hit the ground. I would breathe a sigh of relief at another successful descent without giving myself an ankle injury and then set about collating the maps that had floated off about the place.

Those printed on the thinnest paper stock generally glided the furthest from the table I’d placed in the landing zone. This became something of a sorting system: the oldest maps turned out to be heaviest as they were often mounted on dense linen so, if they were to fall, they had the straightest descent, landing with a dull thud and triggering a pang of guilt that in my haste I might have damaged something precious. The longest flights were achieved by maps printed at the later stages of the Second World War, when the mass printing of maps was well underway, and paper shortages led to some paper maps being printed on little more than tissue paper.

Pristine maps are unused maps and so, while they might be nicer to look at, they are sure to have had much less intriguing histories.

After one particularly chaotic extrication of maps from high up in a drawer marked “Portugal/Spain,” I was intrigued to see that a pre-war tourist map of Madrid had landed further from the stepladder than most of the others. Tourist maps would usually be on slightly heavier paper stock and often folded to fit inside sightseers’ pockets; consequently they tended to land at my feet if I dropped any.

On closer inspection, I saw it had at one stage been folded to an eighth of its full size, and years in the drawer under the weight of other maps had flattened out the creases, as well as yellowed its color, adding to the grubbiness it must have acquired through use. When I picked it off the floor the backside had been facing up, and I could see that, while it was a map of the Spanish capital, the map’s title was in German.

Turning it over, I could see a more detailed view of Madrid at 1:10,000 scale with further annotations and titles in German around the edge (it told me the map on the back was at 1:25,000 scale) and a credit to the famous guidebook publisher Baedeker. The date 1929 was present, but there was another date printed on the bottom right: November 1940.

My gaze was so fixed on the streets of Madrid that it was a while before, out of the corner of my eye, I spotted the stamp to the top left of the sheet. The black silhouette of a swastika was unmistakable. It took a further moment to compute what I was looking at and then to get over the shock. The map I was holding was a witness to one of the darkest periods of history. The dates, the German, the thin paper all made sense and all thoughts of tourists enjoying a visit to Spain left me.

Around the map were key places in the city and the grid references to find them. So, this in fact was a military map, and the faint stamp at the very bottom confirmed it had been captured from the defeated German army, arriving in the map room of the “Geographical Section General Staff” on August 4, 1945. In this case, the Nazis had obtained a guidebook of Madrid that was published in 1929, and then copied it for use in the war (Spain’s neutrality did not make it immune from the possibility of Nazi invasion), a change of purpose that gives the map a whole new meaning.

After tracking down a couple of long-retired military cartographers I learned that tourist maps were often collected to copy for operational charts. Such maps were ideal for this purpose as they were easily accessible, often detailed and regularly updated. I also discovered that the Nazi association with the Baedeker guides, whence the map of Madrid had been copied, had grim consequences for those in Britain who suffered the “Baedeker Blitz” in the spring of 1942. According to the Imperial War Museum, Nazi propagandist Baron Gustav Braun von Stumm said: “We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide.” His motivation for this was revenge for the bombing of Germany’s historic towns by the RAF. The subsequent attacks on the cities of Bath, Canterbury, Exeter, Norwich and York became known as the “Baedeker raids.”

The more I looked at the Madrid map, the more history it revealed. I spotted evidence of another stamp that must have rubbed off from an adjacent map in the same batch. I pondered if this had been a map printed for spies, with its careful folding aiding in its concealment as it moved across war-torn borders of Europe.

Looking even closer I saw the faint line of a fold in the top left corner which appears to push the stamp back on itself so as to no longer face outwards. Quite understandably, a later map reader could not stand the sight of it as they were viewing the map. More than once in the Map Library I came across marks and stamps that had been redacted in this way through folds, cut out or colored over in black ink.

So, a relatively mundane tourist map—first published in 1929—went on to lead an extraordinary life that we can look back on thanks to the marks and stamps it acquired on each stage of its journey: an instrument of fascism in the early 1940s, a trophy of war from 1945 and then, presumably, an educational resource for the remainder of the twentieth century. After this discovery it took me several months of research to piece together how it might have arrived in the collection, but we’ll come to that soon.

We often value more highly a pristine map, but pristine maps are unused maps and so, while they might be nicer to look at, they are sure to have had much less intriguing histories. Who held them? What plans were made, or courses charted?

As I discovered almost by accident on the Nazi map of Madrid, the answers to those questions can often be found on the back of the map, the scribbles in the margins or a fading stamp. With that in mind, I took to paying close attention to these aspects and encountered some lovely surprises.

My favorite involved a sizable map of Cuba, created by a Hungarian-born American cartographer Erwin Raisz in collaboration with a Cuban geographer and cartographer named Gerardo Canet. Raisz was at the top of his game at the end of the 1940s and Canet was keen to showcase some of the latest statistics and mapping for his country, so together they created Cuba’s first national atlas. As part of that project, in 1945 they completed a large map of the island (1.5 m across and 0.5 m tall) entitled Mapa de los Paisajes de Cuba (Map of the Landscapes of Cuba) and I was thrilled to discover the Map Library had several copies of it.

Raisz and Canet spread the island across the full width of the sheet and adorned it with a superb inset of the capital Havana. Along the bottom is a series of intricate drawings showing all the different landscape types of the island such as sandy savannas, pinelands and mangroves. They took inspiration for the colors and symbols from numerous photographs taken on a series of flights over the country. It’s gloriously vibrant and unlike any other map published at the time.

The original map was printed on very thin paper and so a couple of the copies I found were in poor condition. I turned my attention to the one that had emerged from its half-century crammed in a drawer in better shape than the others, because it had been mounted on some kind of linen. As I turned it over and held it up to the light, I thought I was hallucinating when I caught sight of what looked like the black edging of a border to another map.

There also seemed to be faint lines casting a shadow against the linen that weren’t on the Cuban map on the other side. Putting it face up on the table and looking more carefully in the light areas of the sea, I was in no doubt that the criss-cross of lines was in fact a road network lurking in the shallows. I reached for my phone and switched its torch on. Sliding it between the map and the table it immediately illuminated the word “Berlin.”

Part of the problem with the present is that our attitudes change: what we value now may not be what we value in the future.

Cuba had been neatly mounted on a Second World War map of Berlin!

Given that it was completed at a time when there were many surplus maps available and a shortage of good paper stock, a map librarian must have decided to strengthen the fragile map of Cuba, simultaneously pasting over the horrors of the war with the warmth and light of the largest island in the Caribbean. When I invite students into the Map Library, this is one of the maps I like to show them. I ask them to see if they can spot what’s unusual with the map and, when they can’t, I shine my light through with the demeanor of a magician pulling a rabbit from a hat.

Once I knew what texture of linen to look out for, I discovered flashes of war maps on the insides of handmade folders that were assembled to hold loose sheet maps on completely unrelated topics. Only in a map library can time and space collide in such fascinating ways that I would have missed had I been viewing digital copies.

Every time I found a gem like this, I had a feeling in the pit of my stomach that I might be the one to dispose of it, should the worst happen to the collection. I cursed the fact that so many other maps with interesting stories to tell have been thrown away in the haste of disposing of map libraries so that they could be repurposed into classrooms or offices in Britain’s crowded universities. As one retired map librarian said to me:

Without the knowledge, people are throwing away maps they have no idea about, and on the one hand, one condemns it as sort of cultural vandalism, but on the other hand, one has a sympathy with the pressures on space and the need to get rid of stuff…I’m sure the wheel will turn full circle, and, in the future, people will realize what they’ve lost, but dealing with the present is a huge problem.

Part of the problem with the present is that our attitudes change: what we value now may not be what we value in the future, and the dull and ordinary of today may become highly valued curiosities tomorrow. For example, the contribution that a cartographer named Marie Tharp—I will tell you about her in Chapter 10—made to the mapping of the ocean floor was overlooked for decades. In recent years she has been given the credit she deserves, and we can understand her much more thanks to the archive she built of her life that now resides in the Library of Congress in Washington DC. If this archive had not been in her house until the final years of her life, but in a collection that needed to downsize a few decades ago, her maps would have been the first to go to save space for the higher profile—undoubtedly male—mapmakers who will now appear obscure by comparison.

It can also take time to research and appreciate what a map was used for, something I discovered too late when I went to pick over the remains of a map library that was closing for good.

__________________________________

From The Library of Lost Maps: An Archive of a World in Progress by James Cheshire. Copyright © 2025. Available from Bloomsbury Publishing. Feature image UCL Map Library © James Cheshire, 2025.

James Cheshire

James Cheshire is Britain’s only Professor of Geographic Information and Cartography. A world-leading map maker, his cartographic creations have been enjoyed by millions. He is an elected fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and has been recognized with many prestigious awards from the likes of the Royal Geographical Society and the British Cartographic Society. His co-authored book Atlas of the Invisible won the American Association of Geographer’s Globe Award. When he is not making, writing about, or teaching with maps, James spends his time scouring eBay for them in the hope that one day he’ll have a map library of his own.