With regard to profitability, the indications are that maritime trade is booming; with more ships plying the seas than ever before, surely that must mean the existence of tempting targets. The presence of cash in the ships’ safes combined with sea lines in the confined waters of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, or in some parts of the Mediterranean, make swift “hit-and-run” attacks launched with speedboats both lucrative and feasible—the formidable natural ambush locations of the past have not disappeared after all.

Nor is it the case that all members of modern-day European coastal populations are so well off that piracy is inevitably viewed as too dangerous an occupation in the light of other easier and better-paying professions. There are still relatively deprived coastal communities that do not fully profit from the various economic miracles that followed the two devastating world wars, and whose populations in former times would have become pirates without much hesitation. This is especially the case for the shores of the European Mediterranean: the Greek economy, for example, is still in the doldrums after the Greek government debt crisis starting in 2010, and unemployment, in particular youth unemployment, remains very high. At one time this would have been enough to result in a noticeable rise in piracy in the Aegean Sea, yet today, what could certainly be termed “harsh living conditions” aren’t making people turn pirate.

Furthermore, along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean exists a veritable “arc of crisis” running from Syria and Libya—both of which are embroiled in civil wars—to Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, comparatively weak states with their own groundswells of popular unrest. Plenty of grievances there too, one would have thought. Yet why are the many disadvantaged individuals in this region, with not much opportunity to succeed on the legitimate job market, not motivated to become pirates by the greed factor, either?

The endemic human trafficking and smuggling of migrants across the Mediterranean into Europe conducted by Middle Eastern and North African criminal networks indicate that there are still some hard-nosed individuals willing to embark on at least that variant of seaborne crime. Is people-trafficking so lucrative that they are simply not bothering with the presumably riskier enterprise of piracy?

Part of the answer to this question can be found in the fact that nowadays, there is effective maritime patrolling in the North Atlantic and in most parts of the Mediterranean, which renders acts of piracy less likely to occur than other forms of maritime crime, such as smuggling for example; unlike pirates, whose activities may result in frantic calls for help from the vessel under attack, human traffickers and drug smugglers conduct their businesses clandestinely, without attracting unwelcome attention.

Another and probably more important part of the answer is the lack of societal approval: nowadays, being a pirate is simply no longer seen as “doing the right thing.” The former glorification of pirates has not survived the shift of values that has taken place in almost all current states since early modern times. Where piracy does still exist, this change is nevertheless reflected in the societal composition of pirate crews, who hail almost exclusively from the bottom of the social pyramid; the times when the lower ranks of the nobility and the gentry also became pirates have long since passed. There are probably many factors behind this, among them the loss of influence of the nobility in liberal democracies.

The most important reason, however, is the end of the legal variant of piracy, privateering, which was outlawed in the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law of 1856; it stated unequivocally that “Privateering is, and remains, abolished.” The illegality of privateering was further underscored by The Hague’s Declaration of October 18th, 1907, the Convention Relating to the Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-Ships (“Hague VII” for short). Since then, any member of the nobility or the gentry who feels an urge to go to sea to seek fame and adventure will need to join a regular navy. Likewise, the opportunities being grabbed by today’s foremost merchants are legal, not illegal, with the era of globalization and liberalization offering opportunity enough to get rich by maritime trade. Nowadays, they want to be seen as “swashbuckling tycoons,” not “swashbuckling buccaneers.”

Societal changes over the centuries mean that fearsome tribal warrior societies such as the Vikings or the Iranun and Balangingi no longer roam the seas.In the lands that make up the eastern Mediterranean’s “arc of crisis” today, the tradition of corsairing as a maritime extension of land-based jihad was interrupted and broken by the French conquest and colonization of the Barbary Coast in the late 19th century. The sovereign secular states that gradually emerged during the 20th century had no intention of following in the footsteps of their corsairing forefathers. In the times of Arab Socialism, Islam was deemed to be a spent force anyway. Even now, with many of these coastal states in the throes of civil war and insurgency, a return to the “bad old days” is not on the cards—for practical reasons (almost all resources are needed for use on land), but also due to a lack of interest in such ventures and the absence of societal approval.

Theoretically, this could change if a stridently Islamist faction were to win power in such a coastal state and rekindle the dormant reflex to harass non-believers at sea once again. For example, the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) declared in 2015 that after seizing control of the land (in their case, the Mediterranean coast of Syria and the Northern Arabian Gulf coast of Iraq), they would, God willing, take to the sea in order to continue their jihad against the “Worshippers of the Cross and the infidels [who] pollute our seas with their warships, boats, and aircraft carriers and gobble up our wealth and kill us from the sea.” Whether ISIS would have done so or not is a moot point: since they lost the battle on land, the possibility of them taking to the waves anytime soon is rather remote.

The final difference that separates our time from the earlier periods of piracy is that, quite simply, societal changes over the centuries mean that fearsome tribal warrior societies such as the Vikings or the Iranun and Balangingi no longer roam the seas. The history and tradition of doing so have not been forgotten, but they are mostly commemorated in events and celebrations rather than inspiring people to take up the profession. In such events as the Jorvik Viking Festival in York or the Shetland town of Lerwick’s famous Up Helly Aa festival—in which a torch-lit evening procession of several hundred men decked out in Viking costumes parades down to the harbor, where a replica of a Viking longship is burnt—the tradition of piracy has made the transition from a deadly business to colorful folklore.

History was also refashioned in Indonesia, in this case into a sporting event, with the Sail Banda 2010 yacht race as a historical reference to the Dutch hongitochten. Yet despite this distancing from actuality, and the controversy caused by the former prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, when he dismissively described the then incumbent prime minister, Najib Razak, as a descendant of Bugis (Malay) pirates, for some Malay or Filipino fishermen piracy is still an accepted part of the culture, without much of a stigma attached; something they resort to on an ad hoc basis when industrial fishing fleets from neighboring countries come bottom-trawling with their drag nets.

The Tausugs from the island of Jolo (in the southwestern Philippines) still regard piracy as a traditional and honorable occupation that allows young men to demonstrate “highly regarded virtues such as bravado, honor, masculinity and magnanimity.” Their only nod to modern times is the fact that, unlike their forebears, they no longer embark on slave raids, and settle for commodities such as jewelry, money or weapons.

ISIS’s threat to take their land-based jihad to the sea shows that religion still serves as a strong instrument for “othering,” that is, for dividing “us” from “them,” thus continuing to offer piracy a veneer of respectability, as it did in the previous two periods. In current times, organizations such as the notorious Abu Sayyaf Group based in the southern Philippines describe themselves as militant Islamists—they ostensibly fight for a much nobler cause than simple personal enrichment, and thus appear more like a respectable guerrilla movement than a brutal criminal gang that also conducts piratical raids as part of their business model.

Similarly, though Somali pirates themselves may see any vessel as a legitimate target no matter the flag it flies or the religious affiliation of its crew, as we have seen, al-Shabaab glorifies Somali pirates as defenders of Somali waters against a new generation of “Western crusaders.” It is interesting that the centuries-old “crusaders versus jihadists” theme still has some traction—a handy method to explain away the actions of one ’s own side while vilifying those of the other.

__________________________________

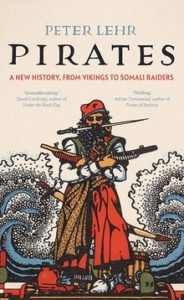

Excerpted from Pirates: A New History, from Vikings to Somali Raiders by Peter Lehr, new from Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission.