When You’re the Target Audience for the Futurist Paintings of a Long-Dead Swedish Artist

Patrick Allington Can’t Stop Thinking About Hilma af Klint

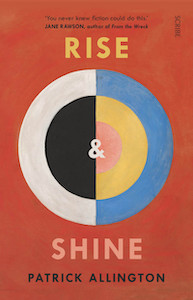

Featured image: “The Swan, No. 17,” by Hilma af Klint.

Until recently, I had no idea that my life was in desperate need of a Swedish artist born in 1862. In the early 20th century, Hilma af Klint began painting visionary, groundbreaking abstract paintings that she dictated should not be seen by the public until long after her death. I am, as it turns out, the target audience.

I was born in South Australia, about as far from Sweden as it is possible to get, a quarter of a century after af Klint’s death and a month before Neil Armstrong stood on the moon. Fifty years after Armstrong’s famous small step, my publisher suggested we use af Klint’s “The Swan, No. 17” as the cover image for my dystopian novel, Rise & Shine. The first time I saw the cover, I barely knew who af Klint was.

In Rise & Shine, the last remaining people on earth can no longer eat and drink. Instead, they feed themselves by watching choreographed footage of war. In this context, “The Swan, No. 17” does not represent, say, ideas about unity, balance, opposites coming together, beauty, grace. It is—this is my spin—the telescopic sight of a soldier trained to wound but never to kill, a diseased belly button sitting on a distended stomach, a toxic body of water, a cross-section of a dead tree trunk, the earth as seen from space, a cancerous cell. And it represents dichotomies unreconciled: war of a sort versus peace of a sort; leaders who embrace fairness but, when they think it necessary, cheerfully resort to despotism; openness versus mass surveillance; the needs of the many versus the suffering of the few; violence versus tenderness.

“The Swan, No. 17” stirred something in me way beyond my personal belief that it embodies the essence of Rise & Shine. My inner world, where I spend a great deal of my time, is a quagmire of everything I’ve ever experienced, seen, heard, read, tasted, imagined. I’m not claiming anything profound about this observation. Each of us has a living, breathing, vast inner world. As it happens, mine is crowded and it’s sometimes louder than I’d prefer. But I like to believe that I exercise a modicum of control over what goes on. While I’m influenced daily by the good, the bad, the indifferent, it’s rare for something or someone to shake things up in a sustained way. Af Klint is proving to be disruptive but in the best possible way.

As a committed over-thinker, I’m enjoying, in a frustrated sort of way, my efforts to make sense of all this. Part of it is simple enough: af Klint’s art is visually arresting and deeply intelligent. Her life—including her evolving worldview, her beliefs, her choices, and the patriarchal forces she endured and continues to endure—is strange and fascinating. Born into an elite naval family, she was trained at the Royal Academy in Fine Arts in Stockholm and became a technically accomplished painter of portraits and landscapes. In the last years of the 19th century, af Klint and four other women formed a group they called The Five. The group’s activities included communicating with beings called The High Ones, and they filled notebooks with automatic writings and drawings. According to curator Tracey Bashkoff, af Klint’s involvement with The Five “would profoundly impact” her approach to her art.

What fun Hilma af Klint could have had with nanotechnology, with big data, with watching an egg explode in a microwave oven.

Whatever motivations drove af Klint, her ambition was audacious. And as the recent documentary Hilma af Klint: Beyond the Visible shows, she had decades of stamina and commitment—the most underrated of qualities in the creative arts. But the world is full of clever people doing original things in weird ways. There must be more (I tell myself). Perhaps it is because af Klint messed with time as well as form. Curator Iris Müller-Westermann says that “Hilma af Klint painted pictures for the future” and the New York Guggenheim exhibition was called “Paintings for the Future.” Not paintings about the future but for the future and for the people of the future—rather than for the people of af Klint’s present, who she didn’t think were ready. “Those granted the gift of seeing more deeply,” af Klint once said, “can see beyond form and concentrate on the wondrous aspect hiding behind every form, which is called life.” What certainty, what faith, there is in those words: “those granted the gift of seeing more deeply.”

I chose to write a dystopian satire because the human race is hurtling towards a dystopian reality as if by conscious choice, seemingly willing to put up with societal collapse because we don’t really believe things will ever get that bad, or because we believe the great god Innovation will save us, or because no matter how dire things get it’ll be a boon for the news cycle and other reality television, or because we just want things to stay the same as they always were, whatever that means. It gives me pleasure, or solace, or the illusion of agency, to spend some of my time speculating about the future.

Af Klint would not, I’m sure, think highly of the distinction I make between science (reality) and spirituality (fantasy). She was a medium who believed that beings of higher consciousness told her what to paint. Different eras have different norms—spiritualist beliefs were commonplace in the early 20th century, not least amongst creative types. But regardless of the century I happen to be living in, I am a dedicated secularist. I do not believe that a spirit from a higher place named Amaliel commissioned Hilma af Klint to undertake her life’s work any more than I believe that God made Bob Dylan or that Godzilla walks amongst us. On the other hand, I am setting af Klint up as some sort of prophet, whispering in my ear as I make stuff up because I believe in the power of speculation.

Af Klint’s world extended beyond what we can see with the naked eye to the microscopic and invisible world. She reckoned with science as well as spirits—X-rays as well as seances. What fun she could have had with nanotechnology, with big data, with watching an egg explode in a microwave oven. In 2021, or so I happen to believe, much of the world remains hidden, to our collective detriment. Way too often, we seem content with, or resigned to, this state of affairs—we go out of our way to promote hiddenness.

I wrote Rise & Shine in a fog of my own befuddlement about the future of the world, unable to reconcile my commingled feelings of hope and hopelessness, my mixed fear and desensitization, and my helpless agitation about how those with power do whatever they want whenever they want. Little of this mess of angst and agitation of mine was viewable to others, but I felt it, feel it, all the same.

Most curious is the strange, almost ethereal state that enables the visible to be forgotten or ignored. The visible but invisible comes in all shapes and sizes, all manner of mantra and ideology. I recently saw footage of spiders on the move, swarms of eyes and legs invading human spaces—fences, sheds, houses—to escape flooding in eastern Australia. Although this seems like a warning that the Bad Times are coming fast, that it’s time to hoard food, drinking water and insect repellant, the moment turned out to be a mere photo-op for just another once-in-100-years weather event (floods, fires, droughts, hurricanes, etcetera etcetera). This is a common story: the waters recede, the spiders die or go back to wherever it is they came from—that same place, presumably, where bears shit in the woods—and we get on with our days.

What does complaining about the state of the world or delivering treatises about spiders have to do with Hilma af Klint? Nothing and everything. I draw inspiration from af Klint’s art, as is obvious by now, in ways not faithful to the vision she gave the world. Her art is so full of symbolism and allusion that I sometimes barely know what I’m supposed to be looking at. I admit this not because I believe in willful ignorance but because when I look at af Klint’s art—the swirls and curves, the shapes, the symbols, the colors, the poise, the majesty of it all—it metastasizes into something else entirely. She offers me no salve, other than the example that trying to understand everything all at once, and imagining new worlds and new ways of being, is worth the effort.

I have never seen a painting by af Klint in real life—I have never stood in the same room as her. I will right this wrong later in 2021, COVID-19 restrictions permitting, when an exhibition of her work comes to Australia. I hope beyond hope to see “The Swan, No. 17.” The painting measures 150.5 by 151 centimeters, near enough to a square. In contrast, the cover of my book measures 21 centimeters by 13.5 centimeters: a rectangle. In af Klint’s painting, there is a small triangle at the center of the circles—yet more symbolism. But on the book cover, the pyramid is obscured by an ampersand—the “&” in Rise & Shine. On one level, I recognize this as an act of desecration. If the spirit world does exist, and Hilma af Klint ever deigns to visit me for a chat, I’ll owe her an apology. If she’s willing, I’ll buy her a beer.

But on the other hand, I stand by the symbolism of the ampersand. The best and most important words and phrases in the English language are conjunctions, none more so than “and,” “but,” “or,” and “yet.” Conjunctions give sentences new possibilities, the power to add layers of meaning, to complicate meaning, to recognize legitimate differences, to subvert meaning.

__________________________________

Rise & Shine, by Patrick Allington, is available now from Scribe.

Patrick Allington

Patrick Allington is a writer and editor. His fiction includes the novel Figurehead, which was longlisted for the 2010 Miles Franklin Literary Award. His short stories, nonfiction, and criticism have also appeared widely. His US debut novel, Rise & Shine, is available now from Scribe Publications.