When Your Family Figures Out You're a Writer... and Loves You For It

Melissa Woods on the Unlikely Intersections of

Child-Rearing and Novel-Writing

My first baby is two years old, arms draped around my neck, cheek pressed into my chest. The scent of his musky head is inebriating. I read him a book called Baby Mickey’s Nap. He is convinced that if Mickey naps, he should too. We are still inchoate; neither of us know it, but we will mature too soon. We will satiate our emptiness with stories.

In places, his soft skin turns rough from play. The soles of his feet develop callouses from running barefoot. His sister, born a year later, teaches me that not every kid will nap because Mickey does. The year after this, my husband dies. I’m told that my toddlers will follow me around asking, “Where’s Daddy? When is Daddy coming home?” They don’t. My children know that stories are make-believe. I give up my own writing to deal with my kids’ trauma.

Over the years, I remarry and have four more babies. There is barely time to read, much less write. Time is measured in feedings and naps, in library trips and crafts. My energy is drained. Love multiplies; time only divides. Children are whole and distinct, and yet, as a mother of many, I have to detangle them from one another, from myself. And holding each strand, I see how easy it would be to mess them up.

The year I turn 40, I go back to college and write a novel. Whole chapters of the book are tapped on an iPhone screen in the kindergarten school pick-up line. I write scenes and character-sketches locked in my walk-in closet. As my fingers dance across the keyboard, my youngest child nurses in my lap. But the truth is, I employ as much help as I can afford (sometimes more) seeking that stress-free nirvana of silence. Some say this is selfish. Some believe my husband should be canonized for “babysitting” while I work on my little hobby.

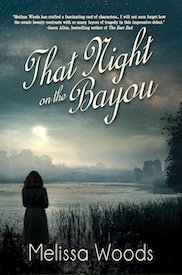

Even after I sign the publishing contract for the book, doubts simmer in the back of my mind. The children are proud. But “Mommy sold a book” doesn’t translate into anything tangible, especially during the months of grueling revisions and edits. All it means to them is that I work even more. They see photos of the cover, the e-galley, the pre-order promos. My kids are nonplussed about the whole publication experience; I feel like a deflated balloon. What is the point of pouring hours and hours into my novels, considering how hard the publishing industry is? I begin to worry that I’m damaging them.

Suddenly, the act of putting words on paper for others to read, to love, to hate, to judge the merits of, is worth celebrating.

Then, one hot August afternoon, my author copies arrive on the doorstep. “Is it for me?” my youngest asks. “Is it my birthday today?”

We drag the heavy box inside and open it.

“Nope, these are mine,” I say.

I hold the shiny book with my name on the spine. The words I have crafted and recrafted are marvelously printed on the inside.

“Mommy, you wrote a book.” My middle daughter holds the paperback close to her chest, and adds, “Can I take it to school?”

“Whoa, look. That’s your name,” says my eight-year-old son James, who is far more interested in Minecraft than reading.

“It is? Where does it say ‘Mommy’?” my four-year-old asks.

My oldest son looks at me with wide blue eyes. The tone of his voice is sweet and simple, and hauntingly similar to when he was two, when we were entangled on the rocking chair. “I can’t wait to tell my friends that you wrote a book.”

That’s when I cry. My husband takes pictures. The kids text their friends. Suddenly, the act of putting words on paper for others to read, to love, to hate, to judge the merits of, is worth celebrating. We drink sparkling cider and have pizza for dinner. They marvel over their names printed on the dedication page.

My eight-year-old son James, who has ADHD and has little time to read, compiles a story about a shark who steals French fries from people on the beach. He types it, with the help of his dad, and binds it with red yarn.

“I wrote three versions,” he says. “This one was the best.”

Love blossoms; time shrinks.

“Sometimes they call them drafts,” I say.

He nods. “I’m working on the first version of my next one.”

I deeply believe that learning in itself is an act of creativity, and it is borne out of curiosity. Reading fosters this curiosity. James does not articulate feelings well, and not in language that is easy to decode. If he trails after you explaining the inner-workings of the world or the intricate details of a video game, he often means to say, “I love you.” His books are meaningful to me, because as any parent knows, we mostly meet our children on their terms. We watch Disney movies and play Candyland. We search for the Rocket leaders on PokemonGo.

That entire month, the kids make books. Many of the stories star my own characters. We print their books on the computer. The little kids learn how to use dialogue tags. We talk about characters and plot and how I come up with my ideas. In my family, for a sliver of time, I am famous.

On the night of parent-teacher conferences, my husband and I drive to the elementary school. I gaze out the window, thinking about what his teacher might have to say, and how I will respond. It is almost dusk, with the sun low on the horizon. Leaves cling to the trees in shades of persimmon, plum, and gold. We get out of the car and walk toward the building, where the sun pokes through the maple trees, dappling the ground with patches of light.

“It’ll be fine,” my husband says, a tight smile pasted on his face.

We know our girls’ conferences will indeed be fine. But James’s teacher might have something to say about his hyperactive behavior, how he talks back when he’s bored. He could be behind in reading again—though probably not math. In the tunnel-like corridor to James’s classroom, we hold hands. His teacher waves us in, and we perch in the little seats, waiting for him to get out James’s file.

“Well,” he says, pushing his wire-framed glasses up the bridge of his nose. “James is a great kid. One of my favorites.”

I wait for the “but.”

“He says you’re a writer?”

My cheeks burn. “Well, sort of. I did write a book.”

The teacher bursts into laughter. “Well, James is quite the writer, too. He’s actually ahead in both reading and writing this year. He’s shown a ton of improvement.”

“So, everything is normal, then?” my husband asks.

“James’s doing great.” He smiles. He shows me the story about the shark on the beach. “I was a little afraid that the shark was going to attack people, and that it would be illustrated.” He guffaws. “But the French fry theft! I was impressed.”

My husband gazes at me and sighs. I sink into my chair. Sweet relief.

I think back to my first baby, and how I stopped writing to meet his needs, to meet everyone’s needs but my own. Love blossoms; time shrinks. You can divide it into tangible chunks, manage it, balance it, hope you get the pieces right. Circling back to the days my oldest children and I wept in each other’s arms in a maelstrom of grief, I remember the stories that filled our empty bellies. I cannot fill anyone’s cup when mine is empty. This book baby will sink or soar, or somewhere in between, and this I cannot control. But my children, whom I birthed and breastfed, comforted and sang to, are proud of me. This is enough.

——————————————————

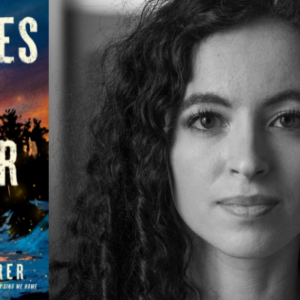

Melissa Woods’s novel That Night on the Bayou is now available from Black Rose Press.

Melissa M. Woods

Melissa M. Woods is an author of literary fiction and suspense. Her debut novel, That Night on the Bayou is now available from Black Rose Writing. You can find her at: https://melissamwoods.com/.