When Your Childhood Belongs to Everyone: Growing Up in a Downtown Manhattan That Changed Forever on 9/11

Emma Dries on Loft Life Above the Fulton Fish Market and the Day That Everything Changed

A few years ago, I went looking for my childhood home on Zillow. This was, of course, a masochistic impulse. It didn’t go particularly well.

My home as I remembered it was a 3rd floor loft in a 5-unit brick building on South Street in Lower Manhattan where historical district regulations kept all buildings under eight stories. My father was an artist, who moved in in the late 70s and built a few rudimentary partition walls that were only suggestions of privacy. It was a long open floor plan with wide-planked wood floors; our front window opened onto a view of the East River, the Brooklyn Bridge, the blinking red numbers of the Watchtower a mile across the water that cycled through time and temperature—stock photo beautiful, really, were it not for the gray stripe of the FDR with angry cabbies running right through the middle.

Inside, light filtered in a gradient through the loft, drenching the front eastern space where we ate our meals and fading out as you moved toward the back where we slept. My older sister and I ran laps up and down through the loft for hours; its size and location would be, with the finances of a freelance documentary filmmaker and artist as parents, unimaginable today.

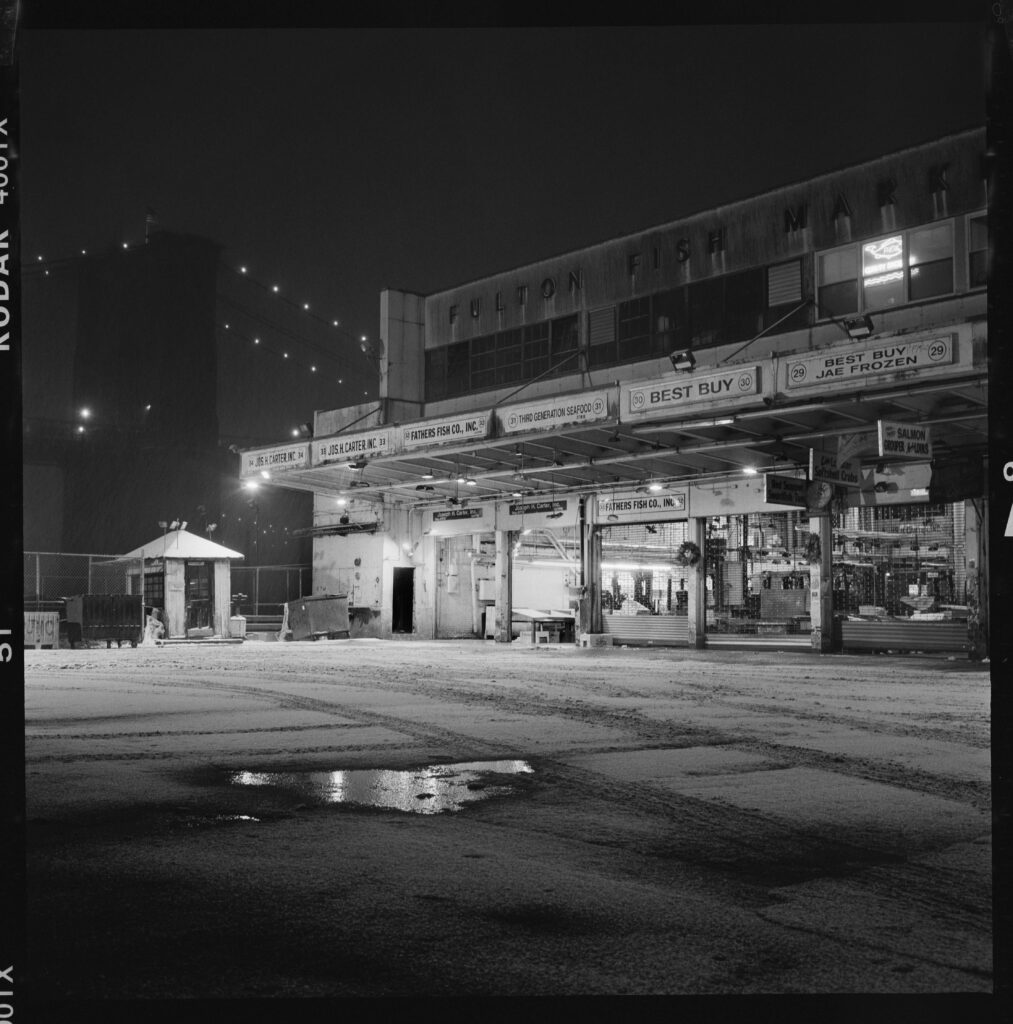

Two floors down, the forklifts of the Fulton Fish Market clamored through the night, but to us it was just white noise. We had no real heating in the loft, just heavy quilts and flannel sheets and radiant heat drifting up from the market offices through the uninsulated floors, and only during the week. Some mornings, large crates of eel on ice blocked our way out the front door. Every so often, South Street would flood.

I haven’t lived downtown in a decade, but South Street found me again in A Falling-Off Place: The Transformation of Lower Manhattan (Fordham University Press; Fall, 2023), the latest book by photographer Barbara Mensch. While many photographers have built careers on documenting Manhattan, few photographed the Fulton Fish Market in particular, with as much detail, through its final eras, as Mensch has.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

The images are striking: The Beekman Ice House, in the early 80s. The 1982 demolition and rebuilding of Pier 17—and another one, 35 year later. The cavernous bodies of headless tuna, laid out on the street. Young and old fishmongers pose, long silver hooks for unloading chests of fish slung over their shoulders. Trash can fires blaze, set by the mongers to stay warm on frigid nights.

With each page turned in Mensch’s book, and as she moves into the 90s, a feeling creeps in, an anticipation of seeing myself: rollerblading with my sister on the Seaport pier; riding on my father’s shoulders as we cross the cobblestone streets to our favorite Mexican restaurant; elbows deep in the community garden my mom helped create; shaking hands with Harry, the old man who used to stand on the corner in front of the Paris Bar in the morning.

Years later I learned, of course, that Harry was likely in the mafia and that it was the mafia that controlled the market and the mafia that arguably kept the neighborhood safe. As a kid, he was just Harry.

*

The second section of Mensch’s book documents 9/11 and the days and months afterwards. When I compare Mensch’s photo of two columns of smoke merging above the towers to the photo I remember my father took on his way to vote that morning—after which, realizing that voting would likely be postponed, he returned home and closed the windows—their vantage points must be nearly identical.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

I imagine Dad and Barbara standing side by side on Gold Street, documenting something they knew would be history but not yet how. My dad eventually deleted his photo: despite his copious, often overwhelming digital archive, this was one thing he didn’t want to remember. As if that was something he could control.

On the morning of 9/11, after my mom biked downtown against the flow of traffic to collect me and my sister from our fourth and eighth grade classrooms, after the south tower fell, after a sound I’ve tried and failed for decades to describe, after we ran, she tried to take us home. But they’d cordoned off access to Lower Manhattan.

We had to stay with friends in SoHo for ten days, returning home to no power and a fridge full of rotting food. Friends who lived in TriBeCa were displaced for months. My elementary school was used as a triage center and we were relocated. We were slated to be back in the building by January but when parents began protesting the scheduled return date to our school building, for fear that there was asbestos lurking in the radiators, my mom tore up a flyer in front of a protestor’s face.

Twenty years later, I would read Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, and one line would lodge itself straight in my throat: “So much ash, so much choking smoke—it was clear to him miles before he reached his home that nothing could be left of it, but he went on anyway.” There’s something unconscious in that pull, and I saw it in my mom during those months: she thought if she could only get us home, everything would be alright.

For several years in my twenties, I worked downtown, right next to the (revised) World Trade Center. I hated it.

Home can center us, it can swaddle, it can alienate, it can isolate. Home is something we can create in our own image, but that very well may go on existing in another form once we are gone. Decisions about whether we choose to leave or are forced to. Whether we never go anywhere. Whether we outgrow our homes or our homes outgrow us.

*

When your own past is subsumed by a collective past, you cannot lock away a memory until you feel equipped to deal with it; it is not yours anymore. What to do with a childhood that, while in some ways singular, private and cozy, is wrapped up in a history of a city that belongs to everyone. When your 9/11 story no longer feels like your own because the beats are worn, known, and predictable, at least to you, served up to each new listener like a surprise treat when they find out you were three blocks away.

I once dated a man who admitted to spending time on the 9/11 subreddit, where posters and lurkers corral around every new photo, clip, soundbite from a survivor relaying their story for the hundredth time. He seemed ashamed, seemed to think I had the power to absolve him of that shame. It was the perverse fascination of a lived history, of an event that teetered on the precipice of a digital revolution that would have made the archival record infinite, as it seems to be today, never more than a click away from the carnage of a war zone.

*

In the fall of 2010, my father died. At the time, he and my mother were separated, I was 17, a freshman in college in the Bay Area and my sister was in her early twenties, living in Chicago. New York City loft law had allowed my father, who was over 65, to remain in our rent-controlled loft after the landlord who bought our building in the mid-aughts had evicted everyone else.

A week after my father died, that same landlord installed cameras in the stairwell to prove that my sister and I weren’t living there full time. We could have fought to keep it but what was the loft without dad? So we took a buyout from our landlord, who subdivided the loft, jacked up the rent ten times, and likely recouped his loss in a few years.

The Zillow listing, when I found it over a decade later, disoriented me. The outline of the loft is familiar, but otherwise the space is a shade of the home I grew up in. I wondered if I returned to the loft, kneeled down and chipped away at the floor, whether I would find the messy splatters of paint that used to cover every surface of my father’s art studio, whether they had filled in the concrete of my handprints on the front windowsill. Would it make me feel any better to know that our ghosts were still there? I can’t check anyway. I know this space belongs to someone else now.

The intimacy I feel with what my home once was cannot be reconciled with what downtown has become.

Of course it’s not just the loft that is different. The Fish Market left five years before dad, replaced by our landlord’s ground-floor wine store. The hollowed-out skeletons of buildings surrounding ours, where squatters used to set fires, have been restored and renovated into seven-figure apartments whose real estate listings tout their exposed brick and historic charm. Cocktail bars sprinkled through the neighborhood now cater to Wall Street and hedge fund happy hours. The only artists who still live there are those who got in early, dug their heels in, and never left.

*

Mensch has done something that seems excruciating to me—to document the change, she had to stay.

For several years in my twenties, I worked downtown, right next to the (revised) World Trade Center. I hated it. Two decades prior, heading across town, we had to navigate tourists who crowded around the barbed wire at Ground Zero, clamoring for a photo of negative space. Now, what’s changed is the technology—selfie sticks—and the smooth granite of the reflecting pools in place of the rubble. What was once spectacle is now sanitized memory.

These days, when I am downtown, I feel a discomfort, a clawing defensive animal snapping at people to get away from my home. I seem to be stuck at two extremes, either looking away, or trying to claim a privileged ownership over a history that I do not own. In shameful moments, I have almost wished another Sandy would surge in, wash it all away for good. It can seem simpler when things are just gone.

In Rachel Cusk’s 2016 essay “Making House,” she writes “Like the body itself, a home is something both looked at and lived in, a duality that in neither case I have managed to reconcile.” Here, she is writing about the physical house itself, but it can be extrapolated to a place like New York, which in many ways can function like an extension of the house itself. In a city so dense, people forgive the need to squeeze into smaller and smaller spaces because their lives spill out into their surroundings.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

From A Falling-Off Place by Barbara Mensch, published by Fordham University Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

In my case, the intimacy I feel with what my home once was cannot be reconciled with what downtown has become: “This juice spot used to be a pizza place run by the mob;” I say to my friends as we walk down Murray Street; “You know these ball fields were twice as large before they crammed in those skyscrapers.” They nod, they’re tired, they’ve heard this all before. The irony, of course, is that most of the streets are landfill, anyway and 50 years ago, Battery Park City didn’t exist at all: it’s manmade, artificial, built from the dug-out foundations of the first World Trade Center.

*

I have been thinking about my father a lot in the last few months; how he gave me his political conviction, how he understood that politics were personal, how personal his own politics were, how they got him into trouble a lot of the time. I have been thinking about him in particular since a few days after October 7th when, in my car, I caught the crackling transmission of the President’s speech on NPR: “…if the United States experienced what Israel is experiencing, our response would be swift, decisive, and overwhelming,” Biden said, and I felt the dread creep in.

My dad was a major evangelist of the budding digital age, which also meant keeping extensive archives, and this included a 70-page thread of his emails he’d compiled and titled “Family Feud.” He was one of fifteen children, born poor in rural Iowa to parents who both died before he was fifteen; because the siblings who were still alive were scattered all over the country, the arrival of email around the new millennium had drawn many of them close again.

“Family Feud” begins with an innocent message from a sibling requesting a recipe in the very early morning hours of 9/11, shifts into frantic emails from family asking my dad to check in and, in the days afterwards, devolves into a political argument so polarized and rife with conspiracy, hyperbole, and non sequitur, that it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine it as a Twitter fight from 2024.

In this thread, one of my dad’s right-wing brothers called for boots on the ground in Afghanistan. My dad was apoplectic. He wrote: “As the dust settles and the debris is hauled away we are now being inundated with smarmy sentiments and American jingoism. Let’s hope it doesn’t inflate to the point where we lay a carpet of nukes over the mid-east.”

In subsequent emails in the thread, his tone softened: he spoke of crying, of being scared for his children, of not knowing what our reaction should be. My dad’s emotional response to terrorism was, of course, terror. Still, he saw the writing on the wall: he saw the way our wound would be coopted by a dangerous political reaction that unleashed our anger overseas and plunged an entire region into ceaseless violence. When he launched a “WebLog” in 2004, he kept a running ticker of Iraqis killed during the US invasion.

We were at once damaged and privileged. We had borne witness to an act of war and yet were completely spared from the repercussions of the perennial war that followed. On September 17th, 2001, Susan Sontag wrote in the New Yorker:

Let’s by all means grieve together. But let’s not be stupid together. A few shreds of historical awareness might help us understand what has just happened, and what may continue to happen. “Our country is strong,” we are told again and again. I for one don’t find this entirely consoling. Who doubts that America is strong? But that’s not all America has to be.

In any case, 23 years and several wars later, we know which line of thinking won out.

*

I did, just last week, steel myself to walk past our old building, which I hadn’t done in years. I was surprised to find it not particularly changed from our landlord’s initial renovations several decades ago; the same tacky, gold-plated buzzer he installed to pantomime refinement; the same comically large, low-hanging bottle on the wine store awning that our neighbor once not-so-jokingly threatened to deliberately hit his head on so he could sue. A few fancy restaurants litter the ground floor along the block. But it was the building directly next to ours that gave me pause: boarded up, graffitied, decrepit air conditioners hanging precariously off the windowsill, a For Sale sign prominently displayed.

I knew what it likely was—developers passing the buck, no one yet incentivized enough for a gut renovation, and what it wasn’t—a statement; and also what I shouldn’t feel about it—happy, because vacancies during a housing crisis are never to be celebrated, even with a building that will absolutely never be affordable again. And it wasn’t so much happiness, but a tiny kernel of sad relief to see the building not so much suspended in time as resisting it. I didn’t know, and still don’t, if this is what I would have wanted for mine.

*

When I first pitched this essay, my editor Jessie Gaynor wrote back and said that hanging in her living room was a sketch of the Fulton Fish Market in the late 70s that a friend of her mother’s drew. She sent a photo. There it was: my home, just as I remembered it, front and center, unmissable.

Emma Dries

Emma Dries is a writer and editor, and an agent at Triangle House Literary. She has worked in editorial at Alfred A. Knopf, Doubleday, Ecco and Flatiron Books, and has an MFA in Fiction from Johns Hopkins. Her writing has been published in Lit Hub, Bookforum, Outside and Dwell and she was the finalist for the Boston Review 2021 Aura Estrada Short Story Contest. She lives in the Hudson Valley.