When Your Books Finds an Audience You Didn’t Expect

Courtney E. Martin on Writing About School Integration—and Being Embraced by Religious Communities

Whenever a writer sits down to put words to paper, at least when publication is the goal, their intended audience looms like specters through their subconscious. Is this the right structure that will pull the reader along? Is this the right tone? The right story through which a fresh idea can be communicated?

I’m a White mother, who wrote very personally and vulnerably about race in post-George Floyd America. Specifically, I wrote a nonfiction book—which people kindly say reads like a novel—about the unfinished project of school integration in this country. I send my two White daughters to a Black-majority, “failing” school in our neighborhood, and I wrote about that experience, and also made a larger journalistic case that it is time for White families to take the lead on integrating public schools—the foundation to our fragile democracy.

here was organized religion, in a sense, saying: we embrace you. We see what you’re up to here. And we’re in it with you.

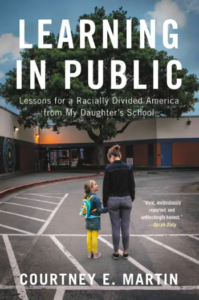

I went into the hardback publication of Learning in Public: Lessons for a Racially Divided America From My Daughter’s School with eyes wide open. I knew progressives, even my own neighbors in Oakland, might be offended; I make an unflinching argument that avoiding Black and Brown majority public schools perpetuates structural racism. I also knew Black and Brown readers might be offended at my inevitable missteps and annoyed by my painstaking self-examination. People might have very valid questions about my motivation for writing such a book: ally theater in the extreme? Career advancement? Money? In other words, I knew I had to be prepared for a range of public reactions.

What I didn’t expect was such a warm and thoughtful embrace by religious communities.

Upon publication last year, I immediately heard from synagogue leaders, Baha’i book clubs, Quaker and Mennonite reading groups, and a myriad of other Christian churches—all eager to make sense of my book through a theological lens. One of the reviews that felt most honoring came from a Christian publication.

This was touching and also a bit discombobulating. I consider myself agnostic. I live in an interfaith cohousing community, so I’m consistently exposed to “people of faith,” but I never join their Bible studies and only rarely have I dropped in on a Buddhist sangha. I grew up in Colorado Springs in the 80s and 90s, which was the heart of toxic evangelical Christianity, so I come by my skepticism of organized religion honestly.

But here was organized religion, in a sense, saying: we embrace you. We see what you’re up to here. And we’re in it with you.

There’s really no feedback more dear for an author. And it was coming from a specter that wasn’t even in my subconscious when I’d sat down to write this book. I’d forgotten that the better angels of organized religion were obsessed with the gap between their professed values and the way they live their daily lives. That, in fact, was the whole exercise of this book project—and these were people who already had the perfect muscles for it.

The most memorable of the encounters I had with my religious readers was with a book club that met seven times(!) about Learning in Public. They invited me to the seventh and last meeting—a Zoom gathering—and spent the hour answering a question while I listened: how did God work on you through this book?

They said things like:

I laughed at the ways I saw myself reflected in Courtney’s self-consciousness.

It made me look at my internalized anti-blackness.

It reminded me not to be afraid of all God’s children.

It was a sacred experience. I was floored that this group of people—mostly Asian American—had invested such a huge amount of time, thought, and spirit in considering what I was trying to do in my book and what it meant for their own lives. I rolled their question around in my head—how did God work on you through this book?

The truth is, I have always avoided romanticizing writing—either as magical or tortured. I write because I’ve always wanted to write. I write because it brings me great comfort and pleasure. I write because I want to be of good use in the world. And the way I write reflects this lack of sentimentality; I don’t wait for the muse to visit me. I stick my butt in the chair, or the 1975 VW bus in the driveway, as was my survival mechanism during Covid, and write. Every day. I get feedback. Lots of feedback, the more merciless the better. And I revise. And I write again.

But as I listened to these Christians talk about my book as some sort of portal through which they were hearing their God speak, I couldn’t help but wonder about the magic of it all. These people—who I never could have imagined when I was organizing Scrivner files and interviewing literacy experts and sitting through school board meetings until 2 AM, when I was writing and rewriting and rewriting—were among the destined recipients of this labor.

In the end, I suppose that is the magic of all books. Authors write with some intended purpose, with some intended audience, and really we have no idea where our books will land—in what hands, in what hearts, in what sacred or profane spaces. We have far less control than we think we do and there is far more beauty than we could ever imagine.

___________________________________

Learning in Public by Courtney E. Martin is available now via Little, Brown.

Courtney E. Martin

Courtney E. Martin is a writer living with her family in a co-housing community in Oakland. She has a popular Substack newsletter, called Examined Family, and speaks widely at conferences and colleges through out the country. She is also the co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, FRESH Speakers Bureau, and the Bay Area chapter of Integrated Schools. Her happy place is asking people questions. Learning in Public is her fourth book.