When You Start an Indie Press With Your Life Partner

From Hogarth to Two Dollar Radio, Beth Kephart Looks Into Literary Labors of Love

Virginia Woolf was self-doubting, self-promoting, and self-consciously vain; she both wanted to be read and feared her audience. History will never know what kind of books she might have written had she not, with her husband, Leonard, created an indie press they called Hogarth—had she not felt free, following her first two novels, to produce her work in precise accordance with her personal ambitions, all while publishing others in whom she believed.

The Woolf’s first letterpress was procured from the Excelsior Printing Supply Co. with income-tax return funds in 1917. It took up residence in the couple’s drawing room. The instructional pamphlet was 16-pages slim. Virginia and Leonard were avowed amateurs.

None of that mattered. Virginia was soon setting the Caslon Old Face type while Leonard worked out the mechanics of the press itself. Their first official production? A one-page flyer announcing their first planned book—a collection of just two short stories, one written by Leonard and one by Virginia. The flyer also announced the Woolfs’ proposed subscription scheme, through which their (imagined) eager readers might enjoy not just the first Hogarth publication, but future ones—books the Woolfs would soon solicit from their wide circle of writing friends, including Katherine Mansfield, T.S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud, and Virginia’s lover, Vita Sackville-West.

If independent presses have waxed and waned since the Woolfs ran Hogarth, our current moment hums with indie press ingenuity and promise—and with a surprising number of indie presses created, Woolf-like, by life partners.

New Beacon Books, Just Us Books, Sarabande Books, Melville House, Small Beer Press X-Artists’ Books, Hoxton Mini Press, Overcup Press—the list goes on. Wanting to know more about what happens when two people who love books and one another forge their own indie operation, I went out in search of stories.

Stan Sanvel Rubin and Judith Kitchen. Photo via Stan Sanvel Rubin

Stan Sanvel Rubin and Judith Kitchen. Photo via Stan Sanvel Rubin

Ovenbird Books

In 2012, Judith Kitchen and her husband, the poet, teacher, and critic, Stan Sanvel Rubin, launched Ovenbird Books, “an imprint dedicated to the publication of innovative and imaginative literary nonfiction”—books “too literary” for traditional publishers, truly creative nonfiction books whose authors cared deeply about matters of form, frame, and language in service of creating not just a story, but art.

Community—among the Ovenbird writers and with Kitchen and Rubin themselves—would be the foundation of this enterprise. Ovenbird would be a cooperative press, using a hybrid business model, in which the writers themselves would take ownership of the look and design of their books and rely on one another to herald each new publication.

Kitchen—a galvanizing teacher and an artisan of books like Half in Shade: Family, Photography, and Fate—brought previous indie press knowledge to the operation, having launched, in 1981, the poetry-infused State Street Press. But Ovenbird’s founding was a more personal, urgent project than previous endeavors: Kitchen had been diagnosed with cancer.

Ovenbird, Rubin recently told me, was named after one of Kitchen’s favorite Robert Frost poems. Having long promoted creative nonfiction as a distinctive literary genre and through a series of Norton anthologies, Kitchen was, even as she began her final illness, eager to publish an MFA thesis of one of her recent graduates. “Characteristically, her purpose was to give life to fine writing that might not find it elsewhere,” Rubin said. “She added her own newest and most ambitious book to the venture, The Circus Train, in order to lend it whatever name recognition she had.”

“You learn so much more about your partner in this way.”

Judith Kitchen Selects featured writers like Steven Harvey as well as Kate Carroll de Gutes, whose Objects in Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear would go onto win the Oregon Book Award and the national Lambda Literary Award for memoir.

The death of Kitchen in 2014 put into question the future of Ovenbird. Then Brenda Miller, who had both written and taught with Kitchen and Rubin at the Rainier Writing Workshop, began to wonder whether one of her own books, a book she now refers to as her favorite, might find a home within the Ovenbird collective.

Miller’s An Earlier Life—a memoir wrought of short, escalating pieces—turned out to be the perfect fit, embodying, as it does, Kitchen’s passion for the beautifully crafted sentence and the intelligently choregraphed sequence. If Miller’s book would be the last ushered into the world with the Ovenbird colophon, the press, like Hogarth, remains a radiant, and radiating force—imbued with the spirit of Kitchen, the ideals of literary community, and a faith in authentically creative nonfiction that challenges convention and eclipses trends.

Bruce Rutledge and Yuko Enomoto of Chin Music Press. Photo via Chin Music Press.

Bruce Rutledge and Yuko Enomoto of Chin Music Press. Photo via Chin Music Press.

Chin Music Press

On their side of a Zoom call during an early August day, Bruce Rutledge, co-founder, with his wife, Yuko Enomoto, of Chin Music Press, shared with me a book called One River, A Thousand Voices. The book presents the Columbia River over a series of accordion folds as well as the words of Claudia Castro Luna, who conceived of the broadside while traveling the waterway in her role as Washington State Poet Laureate. There was, Luna thought, more than words to this story; there was the opportunity to create an enduring objet d’art. And so Luna, who had previously collaborated with Chin Music, shared her vision with Rutledge. Originally designed and set by a letterpress, One River was adapted to facilitate a larger press run.

Rutledge and Enomoto were both journalists working in Tokyo when they founded the press in 2002. The first books were beloved Japanese stories that Enomoto translated into English. They were, as well, “literary objects”—graced by the aesthetic vision of early designers Craig Mod and Josh Powell.

Chin Music Press was still a fledgling operation when Rutledge’s brother, David, a professor at the University of New Orleans, was forced by Hurricane Katrina to leave his ravaged city and take refuge with Rutledge and Enomoto, who were by then living in Seattle. Soon the three were collaborating on the book that became Do You Know What It Means to Love New Orleans?, a collection of essays, art, and remembrances for and about the saturated city.

New Orleans changed Chin Music Press’ sense of identity; it redefined the couple’s ideas about what books might ultimately mean. Rutledge describes the moment when the book was launched in a restored and cherished bar. “I sat there watching the night unfold and thinking about how much bigger than a book this really was,” he said. “This was about community.”

Photo via Chin Music Press

Photo via Chin Music Press

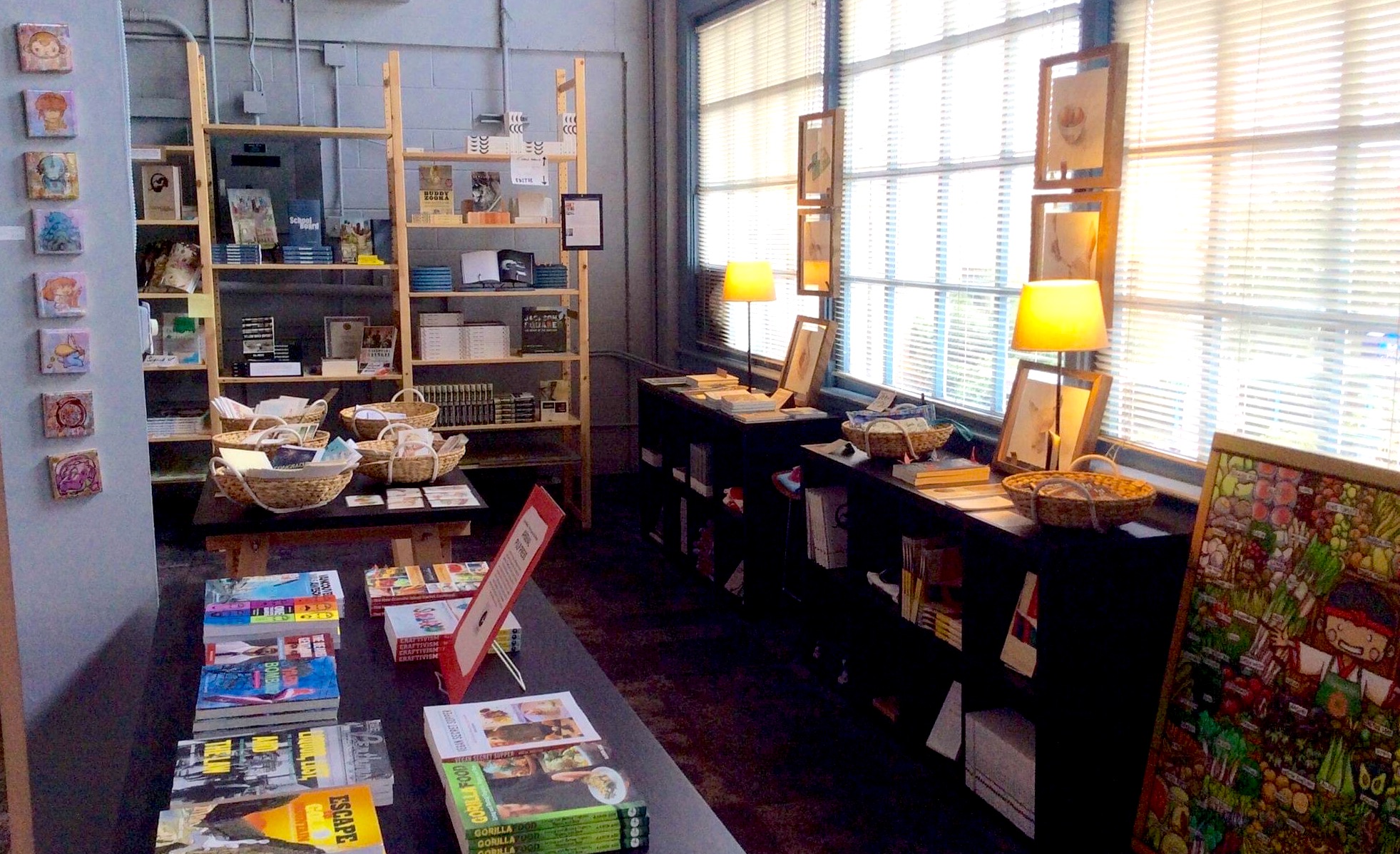

In the intervening years, Chin Music has produced fiction, nonfiction, children’s books, and poetry that explore history, social movements, and the literary, culinary, and horticultural arts. It is, in the best sense of the term, a regional press, celebrated by area residents and critics who spread word of their books into the larger landscape. On 2014, the day of their wedding anniversary, the couple opened, in Seattle’s Pike Place Market, an airy showroom with chewing-gum gray walls and Ikea shelving that displays and sells their wares.

If the showroom is primarily Enomoto’s domain and Rutledge serves as chief editor of the press, nothing happens at Chin Music that they don’t mutually consider. “I’m constantly asking for Yuko’s opinion over dinner and breakfast,” Rutledge said. “It never feels like work.” And because every Chin Music book is both an invention and an adventure, the two perpetually find themselves in dialogue with local artists and communities. Their marriage, they say, is propelled and shaped by the books they make and the space they curate.

“Publishing is a tough business, a difficult one,” Enomoto said. “There are so many challenges, but I would not have it any other way. Once you’ve gone through something like this with your spouse, you are made stronger. With books, you’re always talking about ideas, about life, and once a book is published, once we have had some time with the book in the world, our discussions deepen. We don’t talk about book sales; we talk about the topics we publish. You learn so much more about your partner in this way. This collaboration has brought us so much richness.”

Mandel Vilar Press

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Robert Mandel, a PhD in European Intellectual History, was on the hunt for a permanent university teaching position, the publishing world opened its door. He took a series of positions within scholarly and academic presses that allowed him to seek and solicit books focused on multicultural stories. Dena, Robert’s wife, traveled with him, press to press, teaching Jewish studies and English at each university post. Their ever-growing collection of books traveled with them.

By 2013, it was, it seemed to them, time to retire. Their friends disagreed. Cynthia Ozick, whose out-of-print books Mandel had reissued as part of his Library of Modern Jewish Literature series, urged Mandel to “give great literature a second chance with a new generation of readers.” Thane Rosenbaum, a lawyer and award-winning writer, encouraged Mandel to consider the possibilities of a press fully committed to genuine diversity—to fostering conversations across cultures.

“Thane pleaded with me to establish a venue for writers of every minority—gender, ethnicity, racial, religious,” Robert said. “He kept emphasizing how difficult it can be for mid-list writers to get their stories told.”

“We wanted readers to understand, through our books, who we are, what matters to us.”

There were other “retired” professionals willing to participate, on a freelance basis, in the design, copyediting, and production of such books, along with a former publishing colleague—Irena Vilar—whose foundation, the Americas for Conservation + the Arts, could provide an umbrella for such a publishing enterprise.

And then there was Dena herself, who could serve as a keen-eyed developmental editor with the patience and skill to perfect the books that made their way to her. Thus, Mandel Vilar Press was forged.

“Instead of working forty hours a week we now work seventy,” she laughed. “A great retirement.”

Rosenbaum offered the newly minted press his novel, How Sweet It Is!, a book about political conventions, Holocaust survivors, and the Jewish mafia set in 1970s Miami. After the book was adopted by the city of Miami to celebrate its centennial, sales soared, with the city itself purchasing 5,000 copies and city dwellers purchasing more. It was an auspicious beginning for an indie press operated by two purported retirees.

When founding a press, “the first books are critically important,” Robert pointed out. “Your books become your brand. We wanted ours to be not just the right books by the right authors, but books that were beautifully designed, printed on quality paper, produced as original paperbacks with flaps. We wanted readers to understand, through our books, who we are, what matters to us.”

Today, the 70-hour weeks continue, with the press receiving some 20 manuscripts each week for review and producing, on average, six to eight books annually. Sometimes, the press collaborates with other indie operations to produce books in collaborative fashion. Always, the two rely on one another.

One of the newest MVP productions is Asylum, A Memoir of Family Secrets, by Judy Bolton-Fasman, an exquisitely suspenseful and literary book that has gained critical traction since its release in August.

“I mean,” said Dena, when asked about the memoir, “what’s not to love? Judy writes about inheriting her Sephardic, Spanish/Ladino-speaking culture from her mother, her enduring questions about her Ashkenazi American patriot of a father, and the mysteries that swirled at the heart of the marriage. Judy’s book lies at the absolute epicenter of all we do, and beyond that there’s such clarity, such coherence, such a love of language on every page.”

Kimberly Dawn Stuart of River Glass Books. Photo via River Glass Books

Kimberly Dawn Stuart of River Glass Books. Photo via River Glass Books

River Glass Books

Copy 114 of 200 of Into Night’s Tent, a handbound collection of poems by Stephen Frech, arrives via USPS alongside Katie Manning’s collection of prose poems, 28,065 Nights. They are books that cause the recipient to pause, to absorb their quiet power. They are books produced by River Glass Books, a publishing enterprise created by Kimberly Dawn Stuart and her husband, Marley Stuart.

“River Glass Books was born in one half of a shotgun house in the Carrollton neighborhood of New Orleans, on a street near the sleepy graveyard closest to the riverbend,” Marley wrote to me over email. “Those free little libraries are ubiquitous there, handmade boxes outside people’s houses, filled with books. We spent many nights wandering the streets with our dog, adding freshly-bound books to the inviting wooden boxes, where maybe a neighbor would find them and be fed by the writing. New Orleans imprinted us with its own unique energy, and we try to maintain that spirit of community in our work today.”

Marley Stuart of River Glass Books. Photo via River Glass Books

Marley Stuart of River Glass Books. Photo via River Glass Books

Dawn Stuart and Marley Stuart are themselves writers and editors; Dawn is currently getting her MFA at Syracuse University, while Marley is a graduate of Bennington Writing Seminars. The two credit Jack Bedell, Louisiana’s poet laureate between the years of 2017 and 2019, with encouraging the handmaking of books and the selection of texts in the early days; his spirit, they say, continue to guide their artistic pursuits. They also owe a debt to David Art Supply in Metairie, LA, whose owners and staff gave them time to wander among countless racks of paper and were open to questions, special orders, and ideas.

Today Dawn and Marley work on an old, wooden dining table—reviewing texts, considering materials, threading needles, binding books, preparing mailings. They want each book to feel personal, and enduring.

“Marley puts such great attention into each of the books he designs, and it’s rewarding to finally hold the printed materials in our hands and to spend the time assembling each one of them,” Dawn said. “Our goal is to build books that honor the work of our authors, so we try to make each author’s subsequent run a little different: maybe a new vellum or inset sheet, maybe a new type of thread or a new way to tie it. I feel like all these details matter when holding the physical copy.”

The Two Dollar Radio space in Columbus, Ohio.

The Two Dollar Radio space in Columbus, Ohio.

Two Dollar Radio

Two Dollar Radio is radically committed to work that is, as it says on its website, “for the disillusioned and disaffected, the adventurous and independent spirits who thirst for more, who push boundaries and like to witness others test their limits.”

Books like A History of My Brief Body (Billy-Ray Belcourt) and Whiteout Conditions (Tariq Shah) feature in their catalog, but books are only part of this story. There’s the Two Dollar Radio bookstore/vegan cafe in Columbus, Ohio, the Two Dollar Radio annual three-day cultural arts festival, the Two Dollar Radio film production operation, and the Two Dollar Radio radio show, all which springs forth from the Two Dollar Radio headquarters, where—on the right days at the right hours—you’ll find Eric Obenauf and Eliza Wood-Obenauf and perhaps their two children, who bring their own expressive spirits (and dance moves) to the enterprise.

“We have a long history now of making life-changing decisions without a lot of forethought.”

As a disillusioned high school student, Obenauf came to his passion for books later than Wood-Obenauf, who had loved books so much that she had, in her younger years, constructed her own. But as students at New York University, where Obenauf began to amass a prized book collection, and then as fellow travelers across the west—South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana (before settling for a time in San Diego)—books became, to them, a binding force.

“I must have promised to adhere to all of his book rules enough that he let me read Jonathan Lethem’s As She Climbed Across the Table, which blew my mind and established that we had the same taste, I think,” Wood-Obenauf said. “From that point until today, really, Eric has been my personal librarian, passing on to me the books that he loves, knowing that I will love them too. That relationship is even reflected in the way we run our press, where Eric chooses, signs, and edits the books that we publish, and then passes them on to me to read and copyedit.”

The press began in 2005, when the couple, seeking a lower cost of living, moved to Columbus and obtained a line of credit from a bank willing to fund their dream.

“We have a long history now of making life-changing decisions without a lot of forethought,” Obeanuf said, citing the work of Andre Schriffin and Johnny Temple as helping him come to believe “that something I imagined was inaccessible to us—because we’re poor, had no prior experience, and didn’t yet know the range of responsibilities that went into bringing books into the world—might actually be possible.”

Critical and readerly praise came quickly. Connections grew. The possibilities for two people committed to “making noise” continued to unfold. “I suppose we’re never off the clock,” Obeanuf said. “We could be on a hike in the middle of nowhere arguing about who to send a book to, or cover design. I don’t think our kids would know who we are either if one day we just suddenly stopped talking about writers or books.”

If Two Dollar Radio were not Two Dollar Radio, the two would be making noise in some other way. “What makes the company so special and worth working hard for is that we’re doing it together, we know how much time, energy, and passion we’re each investing, we respect each other for it, and I think that’s been the recipe for success for us,” Wood-Obenauf said.

Beth Kephart

Beth Kephart is a teacher of memoir, the co-founder of Juncture Workshops, and a book artist. She is the award-winning author of more than three dozen books in multiple genres, including Wife | Daughter | Self: A Memoir in Essays and We Are the Words: The Memoir Master Class. Her book Flow: The Life and Times of Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River (Temple) has become a regional classic. Visit her online at bethkephartbooks.com and etsy.com/shop/BINDbyBIND.