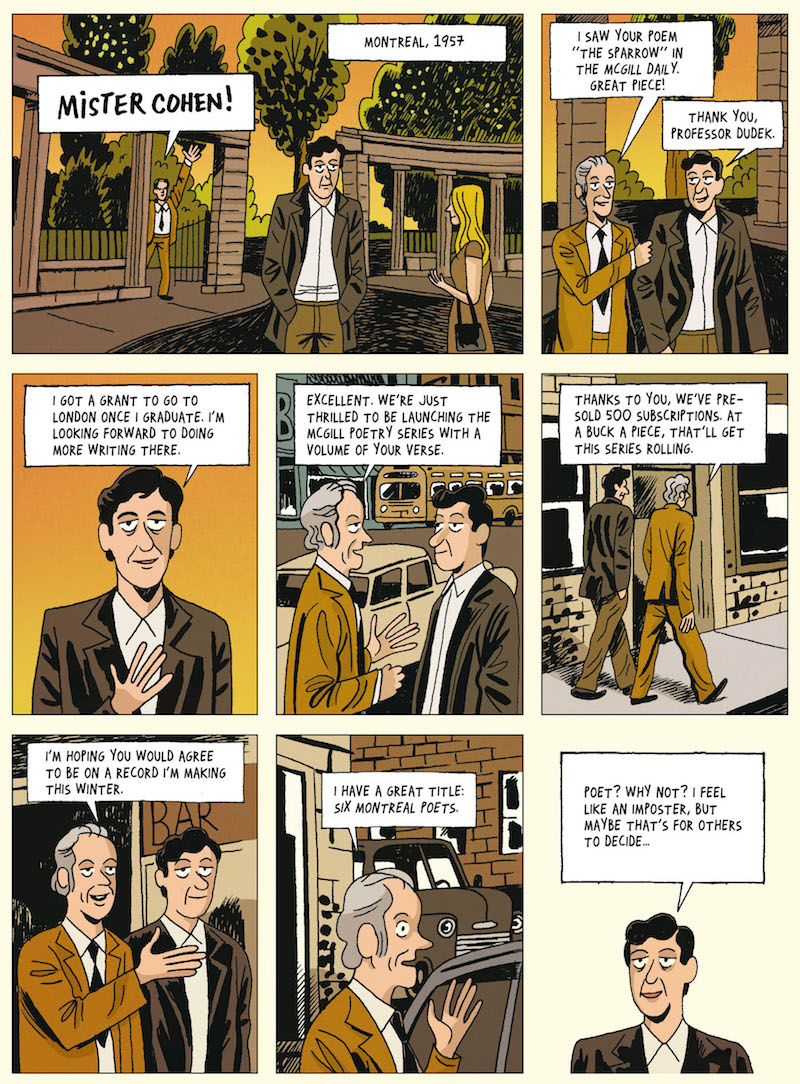

Philippe Girard (Leonard Cohen: On a Wire, translated by Helge Dascher and Karen Houle) and Joe Ollmann (Fictional Father) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a fall event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The driving force behind November’s conversation was the release of Girard’s graphic biography of musician and poet Leonard Cohen.

Both authors have connections to Cohen’s hometown of Montreal and to his work more generally. Their interest in the relationship between the man and the myth came through in this vibrant conversation about the art of biography, hidden narrative structure, and whether art can be made from a place of total serenity.

*

Joe Ollmann: There aren’t many musical characters who have such a universal appeal as Leonard, except maybe David Bowie. He appeals to young and old and hipsters. I don’t know anybody who doesn’t love him.

Philippe Girard: I met one recently.

JO: That’s someone being recalcitrant. What do you think it is about Leonard Cohen that appeals to people?

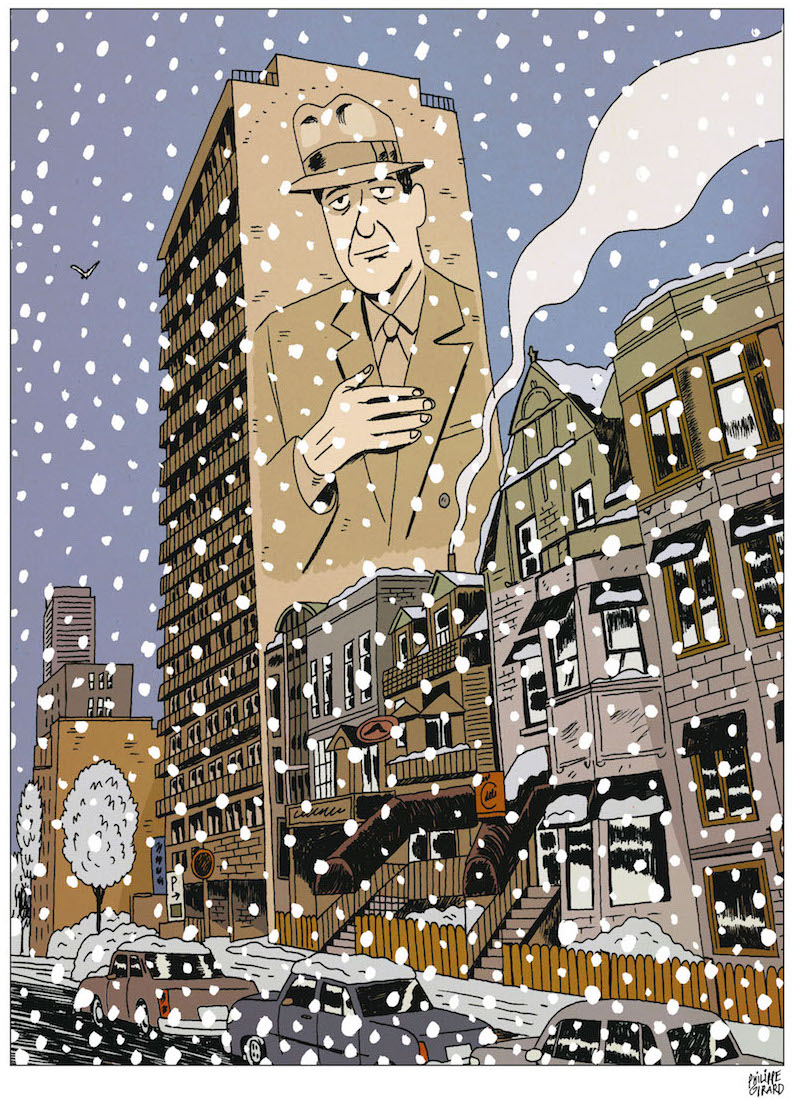

PG: Wow. That’s a tough question. I felt like he was this average guy or rather, this “average superstar” that you might chance upon when you buy a pack of cigarettes or walk the streets of Montreal. He was so special in that way. Everybody who lived in Montreal had the chance to meet Leonard Cohen. He tried to keep things as simple as possible, and that’s what I liked about him. That’s his special ingredient.

JO: Did you ever see him on the street?

PG: Once, maybe 30 years ago, around 1989. Back then I thought every star in Montreal was in disguise with glasses, a fake mustache, a hat, and trench coat. Whenever I was visiting, I tried to spot celebrities, and once I was walking with my cousin, and he said, “Hey. We just passed by Leonard Cohen,” and I said, “How was he dressed?” He said, “Well, like Leonard Cohen.”

JO: I was sitting on Bernard Street, in the window of a coffee shop. He walks by, this beautiful lady has her arm around him, and they’re both laughing. I ran out, and he was just gone, disappeared in a puff of smoke. It was pretty amazing.

Now, in terms of production and research, how long were you working on it, actually drawing the book?

PG: That’s a strange question because before I decided that I would make that book, I had some stuff piling up somewhere on my bookshelf, and then when he died, I thought, “I’m sure someone’s going to publish a Leonard Cohen book very quickly. I’m not going to like it. It’s not going to be up to my standards, and I’m going to be very let down.” Months passed and no book came out. After a while I thought, “Well, maybe I should do it.” That was maybe three months after he passed away. I went to the public library in my neighborhood and took out all the books they had on Leonard Cohen. I read everything. I must have spent four or five months reading and taking notes, and watching every single video I could find, on YouTube, on DVDs, anything. I took notes. It took me a while, honestly.

After all that research, I had so much to put in the book. There were mountains of notes piled up on my drawing table, and at a certain point I had to decide what to use and what to leave. So just then, I drew a Star of David on a sheet of paper, and I decided that each tip of the star would be dedicated to one decade in Leonard’s life, so the 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and 2000s, and for each decade I would focus on one song, one object, and one woman, and of course Leonard’s death was in the middle of the star. So I’d start with one page about his death, then go to one decade, then come back to his death, and then one decade, and come back to his death, and et cetera, and et cetera. So the organization of the story itself came pretty quickly after that.

JO: You actually used that structure? That is a shock because it reads so naturally. I definitely wasn’t conscious of that, but that’s there?

PG: Yeah. I always do that kind of stuff, but you’re not supposed to see it. I’m revealing it to you because you’re my friend and we’re all alone. There’s always hidden stuff in my books.

JO: Wow. That’s remarkable planning. In the end, did you come away liking him more or less after spending all that time with him?

PG: I really loved him. We were talking about David Bowie earlier. These two guys are the most important artists in my life, but in Cohen’s case, it’s different. After working on this book for a couple of years, he wound up feeling like a close friend. We had so many talks in my head, him and me. I would take a bullet for him. I know stuff about him that I didn’t put in the book, and I think that’s what friends do. We protect each other. So that’s how I feel about him. Not that I like him any more or any less. I feel closer to him.

JO: That’s beautiful. I like that.

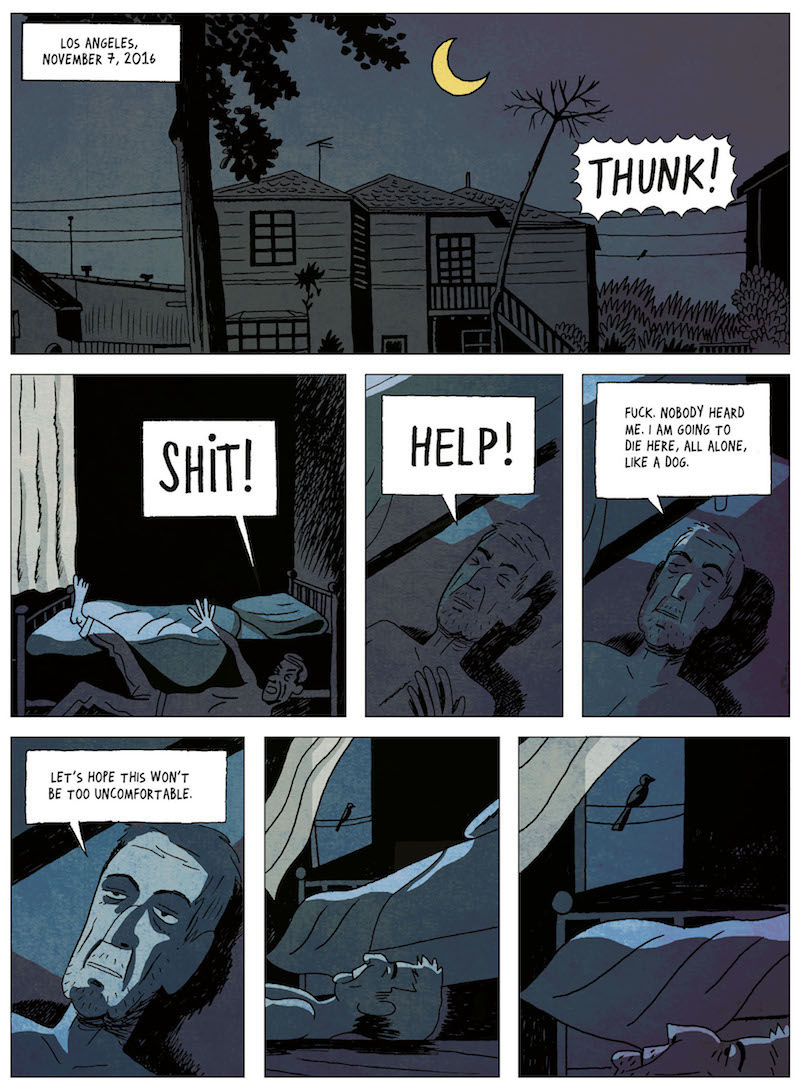

I wanted to ask about this framing element in the book. It’s Leonard dying. I really love the color palette you chose for this. Did that idea come to you right away, telling the story from the end?

PG: Well, yes. I knew pretty quickly that I wanted to start there. Death is one of the most important topics in my books. But particularly for Leonard, it seemed logical: he spent so much of his life preparing for death and spoke so much about it, too. I really like the impact of that first sequence, seeing Leonard on the floor seconds away from dying.

JO: You chose a distinct color palette for Greece, too. All the cities that were important to him, you captured them so beautifully. You’ve obviously got Montreal down. But for LA, you really nailed the freeways and everything. New York as well.

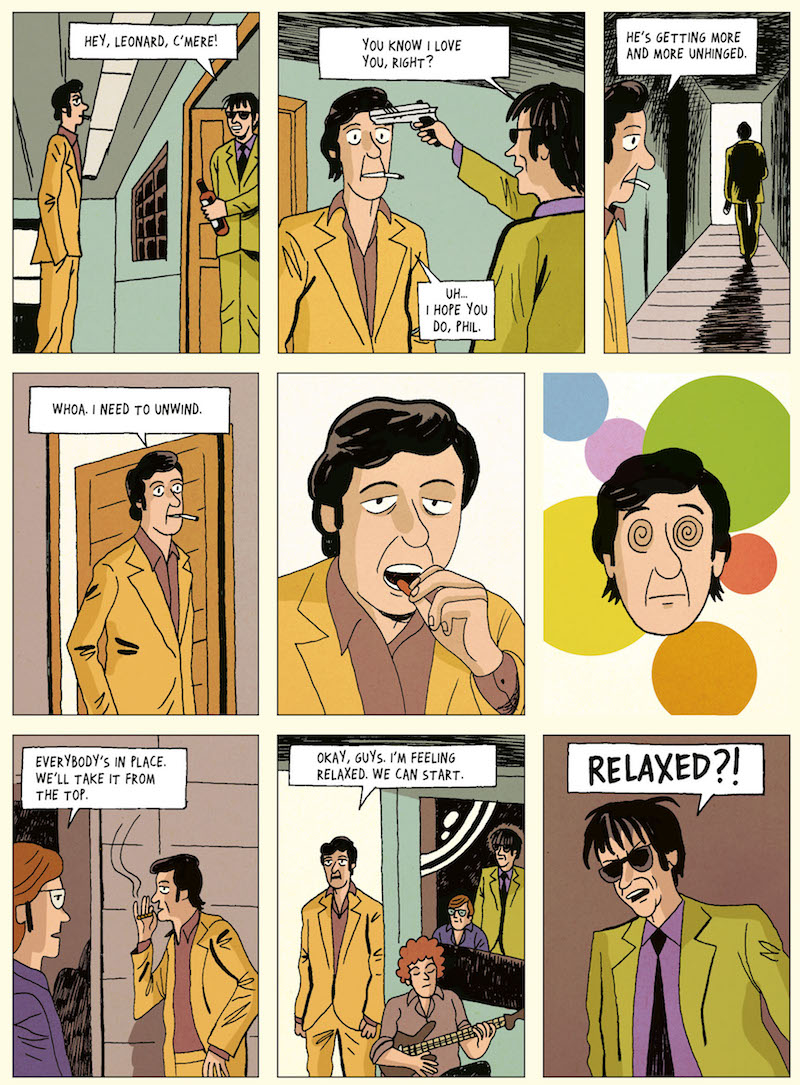

There are a lot of cameos in this book—a whole rogue’s gallery of them. What do you think of Phil Spector? Because that’s a really divisive album, Death Of A Ladies’ Man. A lot of people don’t like that record, though to be honest, I really do. What are your thoughts on that record? Do you like it or not, and then also, what’s your favorite record?

PG: No. I have to be honest. I don’t like it, because now I know how painful it was for him to make it. After reading about it, I listen to it with different ears. My favorite Cohen album is The Future. It’s the first one that I bought, and I’ve listened to it a thousand times. I still like it very much.

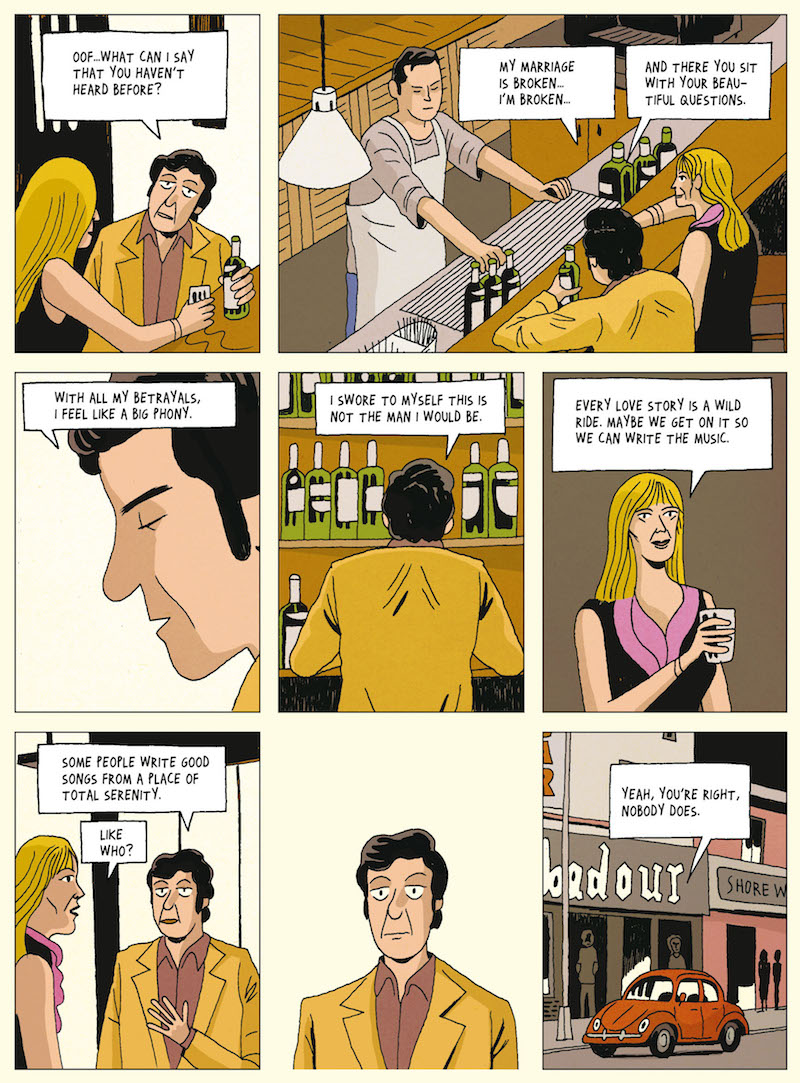

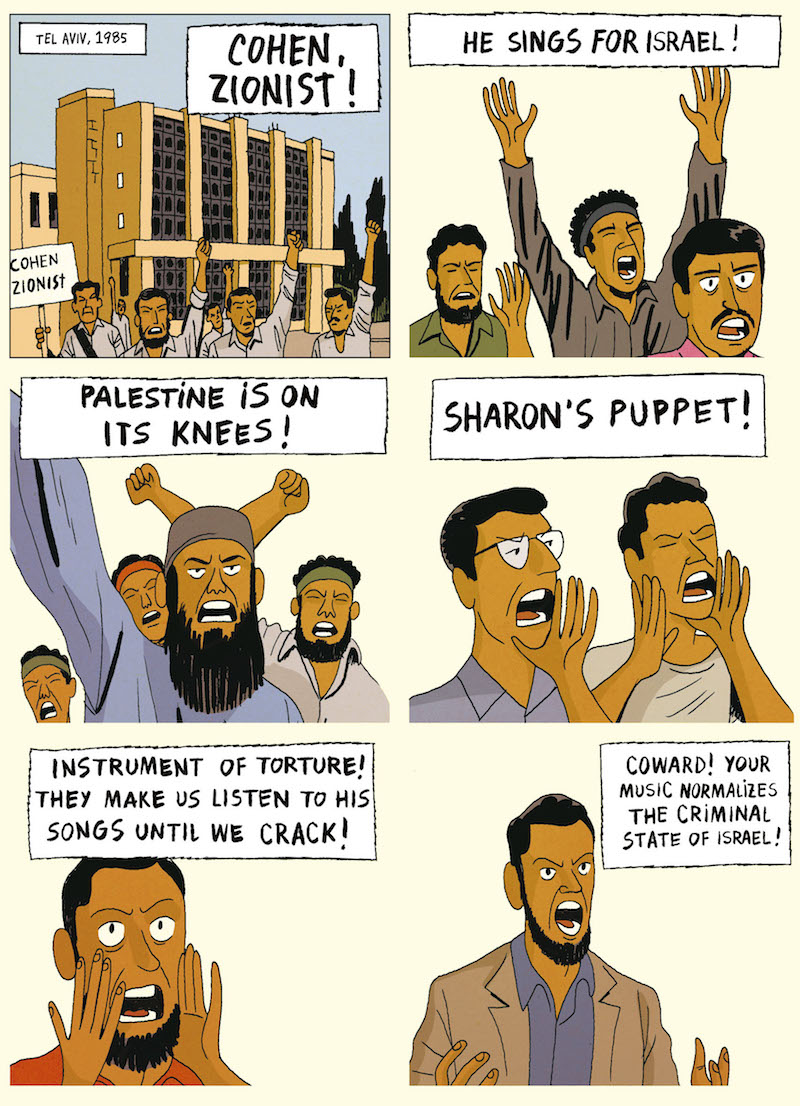

JO: I like the fact that you showed the man’s political flaws and his flaws with his family and his lovers. You didn’t shy away from that.

PG: Once in a while he shows his bad side, and maybe that’s why we like him so much because he’s human. Making a book about a guy you like and only showing his good side would have made the book fake, and I didn’t want that.

That said, I think Leonard Cohen makes for a good character because he’s pure at heart, like Tintin for instance. Of course, he takes drugs, drinks alcohol, smokes cigarettes, and has a sex life, but his quest for the divine and the difficulties he encountered over his lifetime make him pure.

JO: I also like this notion he has, “Some people write good songs from a place of total serenity,” and then Joni Mitchell goes, “Like who?” and he goes, “Yeah. You’re right. Nobody does.” I think there’s some truth to that. I don’t think you need to suffer to make art.

PG: Funny you should mention this page. I had a residency in Poland two years ago. I spent a month there coloring the book, and it rained the whole time—cats and dogs from morning to night—all alone in my shitty apartment in Kraków. So seeing these drab colors and depressing scenes, it reminds me of how sad I was. So, no, you don’t have to suffer to make art, but once in a while, it helps.

JO: It can help, yeah. I don’t recommend it though.

You also show iconic moments like that famous photo with the banana. It’s difficult to do without mythologizing it. But what comes across in your book is that this is a thing that happened, and because everybody adores him, it became gigantic.

PG: Maybe it would have been more difficult for me to bypass the mythos of a French personality, like Félix Leclerc, but Leonard just doesn’t have the same status for me that he does for you as an English-speaker.

JO: Did you interview people that knew him personally?

PG: Nobody. I wanted to talk about my Leonard Cohen. That’s why I wouldn’t describe this as a “biopic,” because I assume that, in many ways, I’m veering away from reality. All of this is just the way that I picture him.

JO: Is this the first time you’ve done a biography?

PG: No. I did one in 2008 about Samuel de Champlain, and it’s probably the worst book I ever did. Every time I see it in a bookstore, I buy it and I hide it in a box in my basement. I really hate that book. So for a long time, I didn’t want to make another one.

JO: You always have very stylized, simple character designs. There’s a certain kind of rigidity to your figures. In this book, though, your drawing is a little looser, and the result is really elegant.

PG: That was one of my goals. I wanted to make the most elegant drawing that I could because for me, elegance is the absolute kindness. Now that I’ve done it, the rest of my work will be influenced by that. I also changed the kind of pencil that I use for drawing. Before I used a brush pen, and now I’m using a really thin and hard-tipped pen. So the line is thinner, and it’s also more delicate, as you said.

JO: What kind of pen is that?

PG: It’s called the Slicci pen. I bought these from a bookstore in Alberta. I bought everything they had, but they don’t make these anymore, so when I’m through, I guess I’ll have to stop making cartoons.

JO: It’s over. You colored this book on the computer, right?

PG: Yep. But I draw on paper before scanning to add color.

JO: Of course.

Another thing about biography is it comes with responsibilities, right? Accuracy, of course, but you also have to negotiate the legacy of the subject and their family and fans. It’s kind of inflexible because you can’t change the narrative of someone’s life.

PG: Well you can, but you have to own that change, and you have to understand that people will write to you, and people may spit in your face. It’s part of the game.

JO: Since the book came out first in French, has it had much reaction from the French readers?

PG: Yes. People have called me anti-Semitic. Some people have written to say I didn’t understand Leonard’s work—a truck load of insults.

JO: If it’s a beloved figure, no one’s going to be completely happy with you.

PG: Yeah. Exactly, but some people are happy. I’ve had nice comments as well.

JO: I think you did a beautiful job.

PG: Well, thank you. Coming from you, that means a lot.

Leonard Cohen came to Quebec City for a show in 2012, I went to see him and after three songs, the arena was jam-packed. He then stopped the show and said, “If I knew that you liked me so much, I would have come sooner.” I thought, “This guy is suffering from some sort of affection deficit,” and he repeated the same thing three days later in Chicoutimi. I then thought, “Oh, my god. Maybe we have a subject here.” That’s something. While he lived in Los Angeles and in Greece as well, he’s a Montrealer at heart. So to me, he’s a Quebecker, and when I look at his life, I see a mirror image of any Quebecker’s life with that “affection deficit,” can you say that in English?

JO: That’s perfect. At a certain point, Leonard says, “I’m a beautiful creep.” He seemed like a person that embraced his weirdness, which I admired.

_________________________________

Leonard Cohen: On a Wire, by Philippe Girard and translated by Helge Dascher and Karen Houle, is available from Drawn + Quarterly.