When Will We Pay Attention to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women?

Jessica McDiarmid on the Highway of Tears

The Highway of Tears is a lonesome road that runs across a lonesome land. This dark slab of asphalt cuts a narrow path through the vast wilderness of the place, where struggling hayfields melt into dark pine forests, and the rolling fi of the interior careen into jagged coastal mountains. It’s sparsely populated, with many kilometres separating the small towns strung along it, communities forever grappling with the booms and busts of the industries that sustain them. At night, many minutes may pass between vehicles, mostly tractor-trailers on long-haul voyages between the coast and some place farther south. And there is the train that passes in the night, late, its whistle echoing through the valleys long after it is gone.

Prince George lies in a bowl etched by glaciers over thousands of years on the Nechako Plateau, near the middle of what is now called British Columbia, at the place where the Nechako and Fraser Rivers meet. It is a small city, as cities go, but with a population of about 80,000 it is by far the largest along the highway, a once prosperous lumber town that fell on hard times. Hunkered under towering sand bluffs carved by the rivers, the once bustling downtown is quieter these days, though a push for economic diversification has, in the past few years, brought in a new wave of boutique shops, pubs and upscale eateries.

From the city, the highway runs northwest, passing ranches with sagging barbed-wire fences and billboards advertising farm supply stores and tow truck companies. It winds down from the plateau toward the coast, passing through ever-narrower valleys where cedar and Sitka spruce and hemlock rise from beds of moss and ferns to form a near canopy as the skies sink lower, the mountains loom higher. The air grows heavier as the highway draws closer to the Pacific, clinging to a ledge above the Skeena River blasted from the mountainsides to make way for trains and trucks, where the margin of error is only a few feet in either direction. Those who err are often gone forever, lost to a river that swallows logging trucks and fishing boats alike. Those who disappear in this place are not easily found.

The towns owe their existence to the railway that carved a path from the Rocky Mountains to Prince Rupert just over a hundred years ago, propelled by fears in Ottawa of an American invasion and hopes of selling prairie grain to Asia from a port on the northern Pacific. The last spike of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway went into the ground April 7, 1914, just a few months before Europe erupted into the First World War. Settlements grew along the railway as livelihoods were wrested from farms forever beset by late springs and early frosts, from towering forests that carpeted the hills and from mines from which men chipped out silver, copper and gold to load onto boxcars going somewhere else.

No one knows who the first Indigenous girl or woman to vanish along the highway between Prince Rupert and Prince George was, or when it happened.

But before these towns named for railway men, fur traders and settlers, there were other communities here. People inhabited this land long before history was recorded in any European sense. Before the Egyptians erected the pyramids, before the Maya began to write and to study the sky, before the Mesopotamians built the first cities, Indigenous people lived in this place. Only about two hundred years ago did Europeans arrive in the Pacific Northwest, seeking sea otter, gold and, later, lumber. Soon, the nascent government of Canada would claim the territory as its own and seek to assimilate or destroy those who had been here for so long. Settlers arrived on foot and in canoes, then on railcars and steamboats, and then on the highway. By the early 1950s, a road connected Prince Rupert to Prince George, though it was little more than a gravel strip in places and often rendered impassable by snowfall, avalanches and landslides.

Soon, Highway 16 was extended across the Rockies to connect the northwest of British Columbia to Edmonton and beyond, opening this vast region to the rest of the country. The road was dubbed the Yellowhead after the Iroquois-Metis fur trader Pierre Bostonais, known as Tête Jaune for his shock of bright yellow hair. And so it remained, until what it brought earned it a new name: the Highway of Tears.

No one knows who the first Indigenous girl or woman to vanish along the highway between Prince Rupert and Prince George was, or when it happened. Nor does anyone know how many have gone missing or been murdered since. In more recent years, grassroots activists, many of whom are family members of missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women, have travelled community to community to collect the names of those lost. Their lists suggest numbers far higher than those that make their way into most media reports, but they are still incomplete—people who have been gathering names for many years continue to hear about cases they were unaware of.

“Every time we walk out our doors, it’s high risk.”

The RCMP has put the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada at about 1,200, with about a thousand of those being victims of homicide. The actual number is likely higher; the Native Women’s Association of Canada, or NWAC, and other advocacy groups have estimated it could be as high as four thousand. And although the RCMP reported that the proportion of homicide cases that were solved was about the same for Indigenous and non-Indigenous women and girls—88 and 89 per cent respectively—NWAC research into 582 cases suggested that 40 per cent of murders remained unsolved.

According to the RCMP, a third of the 225 unsolved cases nationwide were in British Columbia, with thirty-six homicides and forty unresolved missing person cases, more than twice the next-highest province, Alberta. The entirety of northern British Columbia is home to only about 250,000 people, or about 6 per cent of the province’s population. Around the Highway of Tears alone, a region that is just a fraction of northern B.C., at least five Indigenous women and girls went missing during the time period covered by RCMP statistics—more than 12 per cent of the provincial total. And, in addition to the missing, there are at least five unsolved murders, or about 14 per cent.

The Highway of Tears is a 725-kilometre stretch of highway in British Columbia. And it is a microcosm of a national tragedy— and travesty. Indigenous people in this country are far more likely to face violence than any other segment of the population. A 2014 Statistics Canada report found Indigenous people face double the rate of violence of non-Indigenous people. Indigenous women and girls in particular are targets. They are six times more likely to be killed than non-Indigenous women. They face a rate of serious violence twice as high as that of Indigenous men and nearly triple that of non-Indigenous women. This is partly because they are more likely to confront risk factors such as mental illness, homelessness and poverty, which afflict Indigenous people at vastly disproportionate rates—the ugly, deadly effects of colonialism past and present. But even when controlling for those factors, Indigenous women and girls face more violence than anyone else. Put simply, they are in greater danger solely because they were born Indigenous and female. As one long-time activist put it, “Every time we walk out our doors, it’s high risk.”

Across Canada, as across the Highway of Tears, no one has counted the dead. But whatever the number, too often forgotten is that behind every single death or disappearance is a human being and those who love them, a web of family and community and friendship, those bonds we form that make us strong; those bonds that, when broken, tear us apart.

I was ten years old the first time I saw Ramona Wilson. A photo of her, smiling, black hair cloaking her left shoulder, was printed on sheets of eight-by-eleven paper and hung up around Smithers, the B.C. town where we both grew up. Over the picture was a banner that read: MISSING. Under it was a description: 16 years old, native, 5 foot 1, 120 pounds, last seen June 11, 1994. The posters plastered telephone poles and gas station doors and grocery store bulletin boards throughout town and the surrounding areas for months. But in April the following year, the posters were taken down. She was gone.

I would learn later that Ramona wasn’t the only First Nations girl or young woman to vanish from the area. In 1989, it was Alberta Williams and Cecilia Anne Nikal. The following year, Cecilia’s 15-year-old cousin Delphine Nikal disappeared. In 1994, the same year Ramona didn’t come home, Roxanne Thiara and Alishia Germaine were murdered, their bodies later found near the high- way. In 1995, Lana Derrick went missing. The posters went up, and they came down, but not because these girls got home alive.

There are those who committed these crimes, and there are all of us who stood by as it happened, and happened again, and happened again.

There wasn’t a great fuss about these missing and murdered girls. “Just another native” is how mothers and sisters and aunties describe the pervasive attitude. Police officers gave terrified, grieving families the distinct impression that they didn’t care and didn’t try very hard. Nor did the public rally to the cause in large numbers with donations for reward money or attendance at vigils, searches or walks. Families were often left to search, raise funds, investigate and mourn alone. It was not unusual in the 1990s to hear comments about the “error” a girl must have committed to encounter such a fate, whether it was hitchhiking, prostitution, drinking or walking alone at night. It is still not uncommon.

Too often, these deaths and disappearances are seen as the result of the victim’s wrongdoing rather than as what they truly are: an ongoing societal failure. Many of the girls who vanished here were not hitchhiking, nor were they sex workers, nor were they doing anything much different than many other young people. But to many of the people living in predominantly white communities, it seemed as though disappearing off the face of the earth was something that happened to other people. And it was, because this is a country where Ramona Wilson was six times more likely to be murdered than me.

I left northwestern British Columbia in my late teens and never planned to return, aside from the odd week or two to visit family. I reported from across the country and overseas, focusing when I could on human rights abuses and social injustice—that was what I cared about, what I wanted to shed light upon, in hopes of playing some small role in fixing it. Over those years, I watched as women and girls in northwestern B.C. continued to disappear—Nicole Hoar, Tamara Chipman, Aielah Saric-Auger, Bonnie Joseph, Mackie Basil—and long felt that I needed to come home to this story. The first time I spoke with local family members who have become some of the strongest advocates—quite literally, national game changers—for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls was in 2009. But it wasn’t for another seven years that circumstances aligned and I returned home to research and write a book.

In June of 2016, not long after I arrived back in Smithers, I had the honor of walking the Highway of Tears with Brenda Wilson, Ramona’s sister; Angeline Chalifoux, the auntie of 14-year-old Aielah Saric-Auger; and Val Bolton, Brenda’s dear friend, along with dozens of family members and supporters who joined them for part of the way. Called the Cleansing the Highway Walk, it marked the 10-year anniversary of the first Highway of Tears walk.

At the end of it, when we arrived in Prince George after three weeks of leapfrogging down the highway’s length from Prince Rupert, Angeline stood on a stage alongside Brenda and Val. It was June 21, National Aboriginal Day, and hundreds of people had turned out to celebrate at Lheidli T’enneh Memorial Park on the banks of the Fraser River. Angeline told Aielah’s story, and then she read to the crowd her favourite quote, from Martin Luther King Jr. “He who passively accepts evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it,” she read out. “He who accepts evil without pro- testing against it is really cooperating in it.”

Not nearly enough people gave a damn when these girls and women went missing. We did not protect them. We failed them. The police haven’t solved these cases, but there are multiple perpetrators. There are those who committed these crimes, and there are all of us who stood by as it happened, and happened again, and happened again. And while we cannot undo what has been done, we can try to understand how this happened, where we went wrong. We can address the myriad factors that make Indigenous women and girls vulnerable. We can make sure it does not happen again. And we can remember them, these young women with all their dreams and troubles and hopes and cares, who should still be here today. I owe them this. We all do.

__________________________________

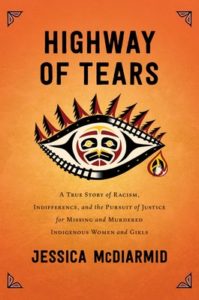

From Highway of Tears: A True Story of Racism, Indifference, and the Pursuit of Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls by Jessica McDiarmid. Used with the permission of Atria. Copyright © 2019 by Jessica McDiarmid.

Jessica McDiarmid

Jessica McDiarmid is a Canadian journalist who has reported on human rights and social justice from around the world. She grew up near the Highway of Tears and has been investigating the murders for the past five years. Highway of Tears is her first book.