When Two Feminists of Color Fall in Love

Ana Castillo on Validation, Rivalry, and Other Women

So far in life, I’ve been truly in love only once with a woman. How it came to be was like a personalized meteorite had plunged from the sky faster than the speed of sound and left a radiating crater in my chest. It felt like a nonstop poem in progress and I couldn’t get hold of its meter or rhyme, if, in fact, it held any. Identity, literature, and the G-spot combined in a single fuse. Because of my cynical disposition, I went around suspicious that soon the gilded fuse would be lit and—boom—game over. Such a potent combination in the heart of a young brown woman poet would surely be the death of her. It wasn’t because I had fallen in love. It was that part of me had been validated. Validation proved my existence.

What do I mean by validation? It meant that another person recognized how I saw the world and did not judge me as loca. And what I mean by crazy here is not the kind where you’d find yourself in the loony bin or more often now on prescribed drugs. I refer to the crazy that people think you are because you don’t agree with the system or how it treats you as a woman—tap-tap like water dripping every waking second and you must be loca because you’ve set out to challenge it.

That is what being in love is about, after all, being validated. It was my lover, however, who put the match to munitions during our first rendezvous out of town. It is why this love story is about the end, because the end started so near the beginning.

Regarding our getaway, a friend lent us his apartment near the beach in Carmel. I left my toddler in the care of his father and she and I drove to the coast. I want to say it was late spring or early summer, but the sea is always cold in Northern California and the waves often choppy and gray like they were on that occasion. We took pictures of each other along the hostile shore. (I assume we did, but I don’t believe I have any.)

I don’t recall what we ate, if we stayed in and cooked or had romantic dinners out. I am only certain that we mostly did what newly minted lovers do best, especially away from society’s scornful eyes. It was after sex that my beloved told me what would change our course. She was hopelessly in love with someone else. It was a much older woman who was “ostensibly straight” and had refused to come out.

We had been fucking like two starving porn starlets for days and nights. I learned things about my own body that you couldn’t find in books. (My copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves was worn thin. It had helped me through pregnancy and childbirth. It was the 80s and, of course, there was no Internet. There had been The Hite Report in the 70s, which led me to a kind of I’m OK–You’re OK view about my desires. But there were things you couldn’t know from books even if they came with diagrams.) My lover’s confession was so incongruous with our heated coupling that I had no way to process the letdown.

The other woman was not at fault for the infliction that began to fester where the meteorite had landed. Apparently, after a tryst that had occurred perhaps two or three years earlier, she’d made her feelings clear. She wanted only to maintain the friendship, which had a basis in their shared radical feminist-of-color views. If literature fed our souls as writers, the content of that literature was the acknowledgment of our perceptions. Our writing made them real. I had nothing but respect for their alliance.

Feminists of color had to be united. The two hadn’t been sharing cups of sugar across the fence and one day decided to fuck and see what it was like. In the 70s and 80s, meeting a feminist of color was like meeting someone from the Resistance. These underground liaisons were so vital to the greater cause they sparked all kinds of heretofore forbidden feelings. One held on regardless of personal disappointments. As I saw it, the other woman in my lover’s mind had become the “obscure object of desire.” In other words, something my lover couldn’t have.

What I heard from my lover that afternoon when the bubble of what I considered our sublime union had burst was that she wanted that woman to be someone for her that she was not. My head throbbed and ears rang as if I’d just heard a mine explode. ¡Qué barbaridad! Tell me it’s not true! I kept thinking. If the political agenda of the radical feminist lesbian was to have a right to her sexuality, then who was she to object to the choices other women made?

If the political agenda of the radical feminist lesbian was to have a right to her sexuality, then who was she to object to the choices other women made?

It was an era when sexual identity was black and white. There were two genders. There were two sexualities. You were either gay or lesbian or you were straight. You chose one camp or the other. Queer meant being gay and not what it currently refers to now—to being anything in between gay and hetero. When white women who were identifying as lesbian left that lifestyle to be with men, their friends and former lovers might disapprove, but they slipped comfortably into their place in heterosexual society. Women of color were marginalized no matter what.

It was that day, while passions for each other raged and the potential camaraderie as writers seemed boundless, that the end began. With the confession, it was my lover, not the other woman, who became my rival. When I wasn’t surrendering myself to our relationship I was planning my escape. If I couldn’t have her, she would never have me. Nora in A Doll’s House comes to mind now and maybe did then. It wasn’t freedom from a man that I sought. It wasn’t that I had to prove myself capable as a woman on my own. I was not going to live reflected in someone else’s idea of me.

As time went on, her feelings for the other woman, who lived on the East Coast, didn’t seem to diminish. A year or so later she pronounced again, pounding her chest and with tears streaming, how she wished the other woman would get out of her heart. It was then that I learned how love could be sometimes. You could utterly abhor (intermittently) the one person you most loved. Whether this was a truth or not, I am certain that was what I felt from the door of our bedroom, watching her cry. In our bed with me so near, she agonized over an unrequited love.

In many ways, the other woman wasn’t only irrelevant to our problems, she wasn’t real. I felt this despite a framed picture of her that my lover kept on display. For a long time I thought it was her grandmother. When I realized who the hunched woman with bifocals and bun was, it became a good lesson in feminism. Now past the age of the woman in that picture, I am glad to know that real passion has no age or aesthetic limits. In straight relationships, many women suffer the humiliation of being left for younger women. It used to be that cross-generational same-sex couples were not infrequently formed. As same-sex attractions became more acceptable, looks and factors like class and race that applied in straight society crossed over, too, and such couples don’t form as much these days. Ageism, however, is alive and well. But back then, what brought same-sex people together was mostly their sexuality, which was so marginalized by society it limited the dating pool.

Drama continued throughout our relationship, which lasted three years. Because we were together nearly every day or at least in touch daily, produced two anthologies, traveled near and far, met each other’s families, and lived a public and private life together, those three years felt compressed in intensity times ten. Drama happened all the time, but the farce of the other woman she acted out on an actual stage.

My lover became an actress for her play about the other woman’s rejection. She was on the rise. I stood up at the end, clapping enthusiastically and proudly because that was my role. As a writer, I understood that what one took from life was not what was important but the product one created. Afterward, backstage, I brought her flowers. It was a triumphant evening for her and it would have been among the good stuff, but I don’t recall her treating me on that occasion like a protégé or her lover but, instead, as among her admirers that night. The loneliness was back.

When I got the courage to leave her, she disappointed me again. Rumors came to my attention that my now former lover led others to think that she had given me everything and breaking off with her had broken her heart. When we met I had been married to a man. Gossip came to me that her supporters claimed my departure meant that I had abandoned the lesbian front. It wasn’t that I was more susceptible to chisme than the next person. It was that what I heard rang true of her accusations before we split.

The fact was, I hadn’t left women—I left one woman. Before I moved out of the apartment, she had already replaced me. While I have had romantic liaisons with women and, later, men, for most of my life I’ve remained on my own. During the years that followed our breakup, I was dedicated to producing work, making a living, and raising my son.

During the relationship she had been excited about Mi’jo. We were both in our thirties and questions about motherhood were always present. There was the proverbial biological ticking clock. As women together, however, further challenges were present around adoption: IVF was brand-new and expensive, same-sex marriage was prohibited, partners were not eligible for health benefits or community property. We did discuss adopting a child where she would be the primary mother. Since Mi’jo had a father and mother, she expressed feeling left out. Then there was her identity as butch. She asked herself if becoming a mother wouldn’t go against being a “masculine-of-center woman.” Regarding my child, I had the feeling my kid was a big part of my appeal. (In time, her lament at our breakup seemed to me to be more over the loss of my child than her loss of me.)

This may sound as absurd to young ears today as a time when women couldn’t vote, but it was easy then for women to lose custody of their children. A woman who had an adulterous affair could lose her children. A woman who was living with another woman held an additional stigma. If same-sex attraction was yet being reassessed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders used by the American Psychiatric Association, the general view of the public was that it was a perversion. That view found its way into the courts. My estranged husband would very likely have been able to take away Mi’jo, if he chose. This was all a real threat to being a mother to my child at the time.

I fought for custody for her sake, mine, and ours. In the long run, it felt at times that he wanted (or needed) his dad, not just a man in his life or a new father, but his father. At the moment, the challenge and struggle to keep my son didn’t help the anxiety of all the other challenges she and I were facing as a new couple.

During those months when we shared an apartment, we discussed adopting a child, one for whom my lover would take the role of primary parent. If we split up, she would get custody; as it was assumed, I would have my son.

Soon after that conversation, I was offered a visiting professorship out of town for the next school year. Unable to get work nearby, the job would provide desperately needed income for me. I remember my four-year-old not having a coat that winter in Oakland. His father finally purchased one that looked like he had picked it up on the fly after I had badgered him so much. The vinyl pink girl’s jacket he sent stands out in my mind as a symbol of one of the hardest years struggling as a writer and a mother. I vowed that my offspring would never lack for anything and to stop begging his father for support.

Before the lease was up, I moved out. My child went to spend the summer with his father and in the fall, came to live with me to start kindergarten. She and I didn’t break up. Her theater career was taking off and she had projects that required her presence. We kept up long distance as we were able for another year and at the end of the second school term we finally called it quits. I moved again to another city to take a new residency in order to support my son and my writing.

Soon after we broke up, she visited Mi’jo and me, insisting she had something akin to custodial rights. On that occasion, when my ex-lover in her usual alpha manner gave him some order in front of me, I’d had enough. As she walked off, I yelled for her to do the world a favor and have a child of her own. Sometime after, I would hear she did, but until then, ugly rumors drifted my way that I had taken away “our” son. I think it made a good story for some: the idea that a lesbian activist was being victimized by her ostensibly not lesbian ex. If I sound cynical it is because gossip sometimes does damage.

No question, women could mean emotional hell. Everything I went to women for in a relationship backfired. Women were indomitably strong in all senses, but they could also be weak. They cheated. They lied. They were vain. Like men who were ambitious, they were egotistical. Some women were chiflada and wanted to be pampered. (This didn’t gel with me, unless they were willing to spoil me, too.) Like men, they could fall in love with younger, more successful, or more malleable women. These were the conclusions I drew from my experiences with both. The good stuff went deep and became integral to my core being. The bad stuff? It helped me grow, too.

In general, I haven’t cared much for labels. Sometimes they were important by way of introducing yourself. Many times they were slippery and lacked concision. When you came to the next juncture in your journey, it might call for reassessment and a new description. You weren’t recanting or flip-flopping when you evolved a label to be true to yourself. We shed old skins, morphed from cocoons, transformed. Even if the outside looks somewhat the same, you never come out the same. The new you is real just as you were real in the previous form. A couple of times I’ve been identified by the media as polysexual. What is that? I wondered and looked it up. After some thought, I’ve concluded that it may be accurate.

Perhaps as feminists of color preparing new ground, we were all on unfamiliar territory. It would not be an embellishment to say we went about our public and private lives suited in armor. Our armors were our pragmatic analyses, our evolving theories made from day-to-day living.

Perhaps as feminists of color preparing new ground, we were all on unfamiliar territory. It would not be an embellishment to say we went about our public and private lives suited in armor. Our armors were our pragmatic analyses, our evolving theories made from day-to-day living. I’d broken off a leftist straight marriage to love a feminist lesbian without any game plan. We were making it all up as we went along. Neither could say she was 100 percent right and the other, likewise, wasn’t wrong by default. “Who washes dishes?” “We take turns, of course.” “Yes, but when?” “Now!” “Now? I don’t want to do it now. Don’t try to control me.” “I’m not trying to control you, but it isn’t fair that dirty dishes should sit in the sink while I am trying to concentrate on my work in my room!” “At least you have a door! Close it!”

It sounds funny now. It wasn’t then. Besides the task building of domestic and professional divisions of labor that came up between us as we worked on two books together, I was at times the insecure woman I was brought up to be when in love with a man. To muddle my mind and heart further, my first feminist lover, brilliant and sensitive in so many ways, had issues. As I write this reflection, the matters of the other woman who left her and later, when I left with Mi’jo, to whom she had grown so quickly attached, are not unrelated. It seems perhaps, as I see it now, that fear of abandonment may have been an unexamined issue in her arsenal. If so, perhaps our union had nowhere to go but to end.

A postscript for you. A couple of years after my lover and I split, the other woman moved to the Bay Area and was teaching at a university. She had included one of my novels in her course and invited me to speak at her class. When the session was over and as the students left, she said, “Ana, I meant to ask you something.” At the door, I turned and waited. “Have you ever read Clarice Lispector?” she asked. I had not. Lispector, from Brazil, was from a previous generation and long gone from this strange and wonderful thing we call life.

“Your writing reminds me so much of hers,” she said. Walking slowly across the campus, I wondered who the writer she named was who also supposedly came from the same interior world from which I wrote. I went directly to a bookstore. Reading has always been part of the good stuff.

They say there are two sides to every story. This is mine.

From BLACK DOVE. Used with permission of Feminist Press. Copyright © 2016 by Ana Castillo.

From BLACK DOVE. Used with permission of Feminist Press. Copyright © 2016 by Ana Castillo.

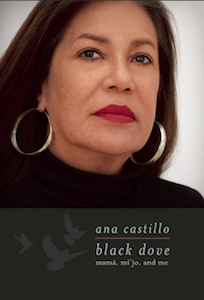

Ana Castillo

Ana Castillo is a celebrated author of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and drama. Among her award-winning books are So Far from God: A Novel; The Mixquiahuala Letters; Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me; The Guardians: A Novel; Peel My Love Like an Onion: A Novel; Sapogonia; and Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma. Born and raised in Chicago, Castillo resides in southern New Mexico.