The conditions of the part-time job weren’t bad. They just weren’t the sort of conditions you came across every day.

The person who’d recommended me for the position was a professor with whom I’d taken a class at university. I hadn’t been back in years. I arrived at the train station by the university, scurried past the roundabout, which could only be described as forest-fire-level chaos, ambled through the gates and up the hill past girls dressed in matching outfits – pyjamas? – into a northwing laboratory where a tattered light green carpet jumped out at me. I was gazing at the expressionless pile carpet as it absorbed the new-student cheers from the courtyard, when an invitation was thrust in my face. An envelope emblazoned with the university name. I glanced up and locked eyes with a face I recognised.

I accepted the envelope with both hands but kept them hovering.

‘I’m sorry. I’m just not sure I have what it takes.’

‘I can’t think of anyone more qualified than you. No one alive, at least.’

The professor looked as though he were addressing somebody behind me.

‘Think of it as a tutoring job. Except that it’s easier. All you need to do is talk.’

‘But she is something of a heritage speaker, and—’

And when you say talk . . . But my next words slipped soundlessly to the ground before the yellow vinyl material, like the final sprays of a park fountain at closing time. As I breathed in and out, puckering my lips in search of an excuse, the professor started to hop on one foot as if he’d got water in his ear. He turned to the mirror to straighten his jacket, and I took that as a sign that our discussion was over. Time to show myself out. I headed towards the exit and spotted the pyjama girls again, this time perched on a bench by the main gates nibbling on matching sandwiches.

The museum was some distance away by bus. Walking from the bus stop towards my destination, all I could see were magnolia flowers and the houses and shops buried under their bone-white petals. Checking and double-checking the professor’s map, I arrived at last at the building I’d been searching for. The bronze doors and concrete walls with remarkably few windows looked ancient, and the building more closely resembled a student dormitory awaiting demolition than an institution where precious cultural assets from around the world were collected and stored. Passing a sign that read Museum Closed Today, I found the back door and took out my phone to call the number I’d been given. The door swung open on the second ring, and I was quickly ushered inside. Like a members only party.

Except this party didn’t seem to be welcoming visitors. Especially those who were alive. It was as frigid as a morgue inside – perhaps to protect the art – and the floors and walls reeked of seepedin chemicals. The chandelier fixed squarely in the vaulted ceiling and the elegant milk glass lamps that lined the hallway cast their soft gazes downward. Strolling past glass display cases of fossils and earthenware artifacts, my eyes landed on a rack by the main entrance with flyers advertising children’s events and local flea markets. Were these events real? Did the dates and times printed on these sleepy flyers arrive at some juncture somewhere in the world, and did children really congregate to do science experiments? Did people lay out their used sweaters and second-hand audio equipment, hoping someone would claim them?

In my line of vision, where everything appeared faded and frozen in time like a page out of an old calendar, the only evidence of life was the curator walking in front of me.

‘Watch your step.’ He turned to me, as though he knew I would catch my hem on the stairs. The curator’s name was Hashibami, and he was astonishingly goodlooking. I couldn’t tell his age, but he looked stylish and youthful in a white shirt and slim-fitting trousers, and his beauty struck me as that not of a human being, but of a piece of craftwork – perhaps a vase, or lacquerware. I gripped the invitation inside my pocket. Handsome men made me uncomfortable. Particularly handsome men who were kind – or appeared so, anyway.

The doors opened at the top of the stairs, and I was drawn instinctively to the arched windows. If there was an argument for light having a gravitational pull, I would have to agree wholeheartedly. Though not visible from the outside, the centre of the building had been hollowed out to make room for trees and a small pond, with a curved corridor above – awash with translucent light – that provided a full view of the quaint courtyard. Pointing out the bouquet reliefs on the pillars, Hashibami explained, ‘We’re standing in the former mansion of a wealthy man who lived in the area and donated this building to the museum. The upper floor houses the collections he amassed over the years, though the doors are closed to the public today.’

A symphonic melody floated out of one of the galleries. I recognised the smooth, uplifting swell of an oboe, and timpani rolls that made me think of excavating old memories with a wooden mallet. Strolling past a door embellished with seashell carvings, I could almost smell the balmy salt air, hear the lapping of the sea. This was a side to the museum I’d not known before; a day of private celebration behind closed doors.

We were headed for a room at the end of the hall. Hashibami chose a key from a heavy bundle and inserted it into the door, unlocking it with a click. I peeked through the crack, ignoring the faint reflection of a yellow raincoat in the hallway window.

‘Right this way.’

This was to be my new workplace, apparently. My shift was once a week, and no experience was required aside from conversation-level Latin. I had been hired to talk to the ancient Roman statue of Venus.

__________________________________

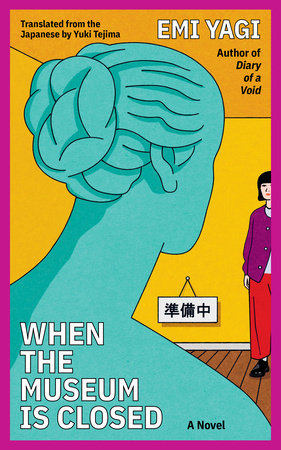

From When the Museum is Closed by Emi Yagi, translated from Japanese by Yuki Tejima. Published by Soft Skull. Text copyright © 2026 by Emi Yagi. Translation copyright © 2026 by Yuki Tejima. All rights reserved.