When the Highest Paid Hollywood Director Was a Woman

Unforgetting Lois Weber, Master of the Silent Film Era

The director Lois Weber had a habit of signing her films, such that several end with a title card in florid script, “Yours Sincerely, Lois Weber.” The obvious analogue is a letter; in this case a letter misplaced for a very long time. Weber was a master of silent film, and for a time she was the highest-paid director in Hollywood. The only woman admitted to the Motion Pictures Directors Association, she was also the only female director among the 250 founding members of the Academy of Motion picture Arts and Sciences. Her notoriety, credentials and budgets rivaled those of D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille. Yet while the birth of cinema can’t be discussed without reference to these names, Weber’s remains largely unknown. Film historian Richard Koszarski wrote in 1975 that she had been “forgotten with a vengeance,” as if the forgetting were aggressive, even calculated. Strategic forgetting is one of the most Machiavellian tactics of the dominant culture: in response to it, the task becomes not only to reanimate the dead but to puzzle out the motives and mechanics of their effacement.

Weber’s films are primarily domestic dramas, stories about family ecosystems and the financial and emotional obligations that bind people together. Behind these narratives are the social and political issues that divided Weber’s audience: abortion, drug addiction, capital punishment, prostitution, anti-Semitism and birth control. emboldened by a medium without traditions or conventions, Weber saw no reason why film should aim to merely amuse when it was possible to change the world.

Weber was called a “propagandist,” but she resisted the word. Propaganda, she said, was too simpleminded. A man would shift his thinking on birth control, for instance, not because Weber advised it, but because he came to feel obligated to remedy the distress of a specific young woman who worked as a laundress and wore her hair pinned at the nape of her neck. Weber understood social change to be the sum of tenderness meted out to individuals. Her films were a concerted experiment to coax this tenderness from viewers reluctant to extend it.

Trade publications and industry transactions establish that in early Hollywood Weber had great clout and a reputation for “intellectual athleticism.” But only a fraction of the output responsible for her stature survives. of the 153 films she wrote and directed between 1913 and 1934, just sixteen have not crumbled to dust or disappeared, and they are scattered in archives from Tokyo to Wisconsin. I have managed to see eight. Some are short, like Suspense (1913), about a woman home with her baby when a burglar breaks into the house. Another, The Dumb Girl of Portici (1916), starring ballerina Anna pavlova, was the result of a studio assignment, and is stylistically unlike the other seven. eight films could hardly be considered a strong sample size, and prudence checks the impulse to celebrate. Yet it’s enough to be convinced that Weber made a kind of film—principled, homely, honest—that was antithetical to what Hollywood has come to represent.

Weber’s 1916 film The Hypocrites, rereleased in November 2018 as part of Kino Lorber’s “pioneers: First Women Filmmakers” collection, made her a household name. it begins as an allegory. A priest sequestered at a medieval monastery is so ardently devoted to God that it irks his fellow priests. He is working intensely on something secret, which he plans to unveil at a grand fête. The camera pans slowly over gathering crowds, representatives of the Family, the trades, the Monarchy, the politicians, etc., all chattering in anticipation. A sheet falls away to reveal the priest’s creation: a life-size statue emblazoned at the base with the title “Naked Truth.” naked truth is in fact exactly what her name suggests—a naked woman standing on a pedestal.

Weber saw no reason why film should aim to merely amuse when it was possible to change the world.

“The people are shocked by the nakedness of truth,” states Weber’s intertitle. Some snicker and some hide their eyes, others pantomime dismay. The sculpture is quickly re-covered, the priest attacked by a mob. Stabbed in the heart, he dies as Weber cuts to the typewritten script of a sermon. A contemporary priest, played by the same actor, preaches to his congregation about hypocrisy. His parishioners yawn and glare and murmur about having him dismissed. Dejected, the priest dozes off after the service, returning in his dream to a search for Naked Truth. She is secluded on a mountaintop, but the parishioners refuse to follow the priest there. The trail is steep and their clothing unsuitable; one man is carrying bags of gold and refuses to set them down.

When the priest, alone, reaches the summit, he entreats Naked Truth to come to his parish. She consents, and the two begin making visitations. Naked Truth carries a mirror, which after each meeting cleverly reveals the hidden truth of the encounter. A politician stumps with a sign, “My platform is honesty,” but the mirror shows him receiving bribes. A man sweetly romances his date, but the mirror reveals his other life as a philanderer and gambler.

Naked Truth is a coquettish phantom. Superimposed on the scene via double exposure, she holds her forearm to her breast to gently hide her nipples. It is sometimes claimed that the actress wore a flesh-colored leotard, but the defined nubs of her backbone—which cloth would have muted—say otherwise. The film ends with one final scene of hypocrisy. The evening after his sermon, the contemporary priest suddenly dies. He is found slumped in a chair at the chapel, clutching a newspaper confiscated from a choirboy. His hostile congregation uses the newspaper to besmirch his reputation. (Reading the Sunday paper broke the Sabbath.) “After preaching a sermon on hypocrisy,” a local paper reports, “it was unfortunate that he should be found with a Sunday newspaper in his hand. the congregation was much shocked.”

In terms of career strategy, Hypocrites comes off like an arcane chess opening. Weber combines scenes guaranteed to attract censors with a narrative that insults their intentions. I imagine her with a gleam in her eye, wielding the title as a dare. If a painter or sculptor could use full-frontal female nudity for high-minded purposes, so would she.

Weber professed annoyance when the film did face censorship, indignantly arguing that the nudity was “too delicately carried through” to be anything besides “a moral force.” The debut was delayed, and Hypocrites was ultimately banned in Chicago, Minneapolis and the state of Ohio. The police in San Jose seized prints, but a court decision eventually allowed them to be screened; in Tacoma, the police captain took a private viewing and declared it acceptable. In Boston, authorities protested they would not allow the film to be screened unless clothes were drawn on Naked Truth frame by frame. Most viewers, though not all, seemed to agree with Weber, and despite the scuffles Hypocrites sold out theaters across the nation. There were extended runs and return bookings.

On Hollywood’s path from sketchy nickelodeon theaters to grand cinema palaces, it was women who played the ushers.

In New York City, the most expensive tickets moved most quickly, suggesting that Weber had attracted the upperclass audience that was early cinema’s holy grail. Hypocrites broke records for highest-grossing film in Los Angeles, Detroit and New Orleans; the year it was released it was reputed to be the “most productive money-getting box-office attraction ever shown in the South.”

Cinema was originally thought to have a special relationship with femininity, and women thrived in the industry’s early days. “In no line of endeavor has woman made so emphatic an impression than in the amazing film industry,” noted a journalist in 1915. Studios prized “female” dexterity for the nimble-fingered work of coloring, gluing, splicing, polishing and editing. In addition, their reputed emotional intuition was often considered a boon for screenwriting and directing.

It’s estimated that women wrote at least half of all silent films, while narrative film—film that tells a made-up story—is arguably the invention of Alice Guy-Blaché. Bored by the Lumière Brothers’ footage of workers leaving a factory, she made La Fée aux Choux (The Fairy of the Cabbages) in 1896. There are actors, costumes, props, sets and a whimsical story; in the surviving clip, newborn babies emerge from giant heads of cabbage with the help of a fairy-midwife. The birth metaphor seems deliberate; the first narrative film may also be the first film about film. Between 1918 and 1922 there were upwards of twenty production companies with women at the helm. At the behemoth that was Universal, eleven women directed an estimated 170 films between 1912 and 1919. Women in film earned some of the highest salaries of any women, in any field, in the world.

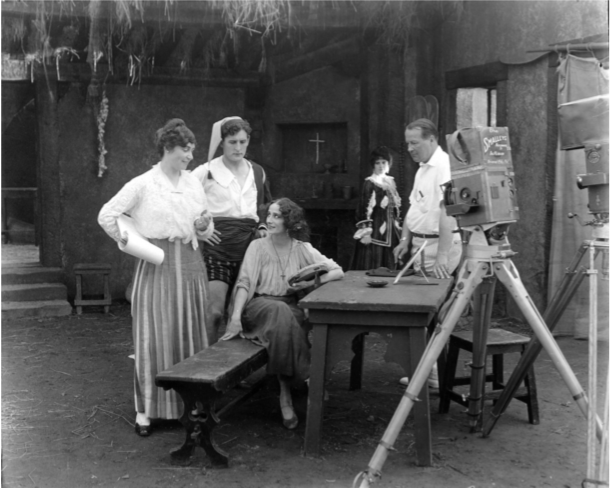

Lois Weber on set of The Dumb Girl of Portici, 1915

Lois Weber on set of The Dumb Girl of Portici, 1915

Women were also symbolically useful as totem gatekeepers of middle-class legitimacy. Considered the weaker sex, but also the more virtuous, they lent their supposed moral superiority to a business with a rough-and-tumble reputation. Hollywood welcomed them. An industry staffed with women like Weber—white, educated, married, Christian—assured middle- and upper-class audiences that cinema was good clean fun. On Hollywood’s path from sketchy nickelodeon theaters to grand cinema palaces, it was women who played the ushers.

*

The name Weber was associated with religion in Pennsylvania long before Lois was born in 1879, outside Pittsburgh in the town of Allegheny. Her father was an upholsterer, but her grandfather and great-grandfather were preachers, and another relative had established the city’s first church in 1782. After a brief stint as a concert pianist, Weber began volunteering with the Church Army Workers, a group very much like the Salvation Army, where she proselytized and sang hymns on street corners. (The Church Army still exists; it was recently headed by the Archbishop Desmond tutu.) As part of the work, she visited brothels, offering prostitutes jobs with the organization. She spent one Christmas with thirteen women she’d enticed to leave sex work, and found it a very satisfying holiday.

Weber turned to filmmaking after her father died, as a means to help support the family. She represented the career shift not as a rupture but as a continuation of her religious work, insisting that her films were an elaborate form of proselytizing. “In moving pictures,” she said, “I have found my life’s work. I find at once an outlet for my emotions and my ideals. I can preach to my heart’s content.”

Weber understood preaching to be an elastic term, one with little relationship to an actual pulpit. The Church Army, like the Salvation Army, embraced unorthodox forms of proselytizing. Services were held in public parks to attract working-class passersby, and converted former criminals often served a special role in exhorting crowds. Both groups were better known for their service than their doctrines. During World War I, the Salvation Army became famous for their “doughnut lassies,” women who fried doughnuts for soldiers in combat helmets. The organization’s unofficial motto was “First, soup; second, soap; and finally, salvation.” Like doughnuts or a warm bath, film seemed to Weber a tool in the conversion toolbox.

Like doughnuts or a warm bath, film seemed to Weber a tool in the conversion toolbox.

Weber wasn’t the only woman to envision an evangelism informed by cinema. Long before megachurches, the twenties and thirties preacher Aimee Semple Mcpherson mesmerized crowds at the largest auditoriums in Los Angeles. Known as Sister Aimee, she performed miracles under colored spotlights while seated on a throne of roses. Her sermons were accompanied by brass bands and her velvet robes trailed the stage. (“I sat under Aimee yesterday, and had 2 ½ spells of tumescence,” confessed H. L. Mencken to a friend. “Her Sex Appeal is tremendous.” His profile of Sister Aimee for the Baltimore Evening Sun was less forthright.) Sister Aimee grew up in a protestant religious family much like Weber’s. As a teenager she began exploring other churches; she was especially attracted to the performative aspects of conversion at pentecostal revivals, and earned an early reputation for the way in which the spirit of God left her convulsing on the ground.

Sister Aimee advised her followers not to go to movies but was herself a master of costume and staging. She occasionally preached in a police uniform, incorporating skits and props into her sermons. She took the stage by running, often with bouquets in her arms. The effect was full-blown spectacle, which Sister Aimee appealingly tempered with humility: “I’m just a little woman, God’s handmaiden, the least of all saints,” she liked to say. The crowds went wild.

Weber likely would have judged Aimee’s doctrine as too fast and loose, but she might have appreciated her populist touch. The new evangelism offered both women opportunities to hold crowds in the palm of their hand, and to do good works even as they earned fortunes.

In spring of 2018, the saviors of almost-lost cinema at Milestone Films released Weber’s 1916 production on DVD. The film had been unseen and practically unknown for nearly a century, but following a revival screening late last year, the New York Times critic Manohla Dargis deemed it “brilliant.” Weber’s inspiration for the film had been a report by Jane Addams about how easily shop girls fell into prostitution. Shoes begins with a subtitle—“She sold herself for a pair of shoes”—and then backtracks through the chain of events that led Eva, the young protagonist, to exchange sex for footwear. It’s a Pretty Woman story turned inside out.

It was apparently easy to slide into lunch-hour prostitution.

Eva works long hours in a five-and-dime store, and her job is the sole support of her father, mother and three younger sisters. Her wages go straight into a pouch pinned to her mother’s bra. Week after week, her mother promises there’ll be enough money to buy Eva a new pair of shoes, but there never is.

The particulars of Weber’s plot are drawn from the report. At that time, according to Addams, shop girls made about $6,000 a year, barely a living wage, while prostitutes earned more than four times that amount. Activists argued that stores cultivated a desire for luxury goods far beyond the means of working girls, whose ten-hour days behind the counter left them standing prey for would-be pimps. It was apparently easy to slide into lunch-hour prostitution, and Weber was horrified that so many young women did.

Shoes doesn’t stray far from its title; Weber attends almost obsessively to Eva’s disintegrating boots. The camera addresses them as a character, lingering over their poignant creases, and following along as they walk gingerly in the rain, stand on rough wood floors or sit abjectly next to Eva’s chair. Every morning, Eva traces and cuts out inserts from cardboard to protect her soles; in the evening, she shakes out these fragments, now dirty and crumbled, and soaks her feet in steaming water. Her hope for redemption seems to hinge on the state of her footwear; if Weber can convey how tattered the boots and sore the feet, we will forgive Eva her prostitution. At the end of the film, passed over by her mother one more time, Eva finds her own solution. She comes home one day wearing a gleaming pair of boots, and tearfully collapses in her mother’s lap.

Footwear is important in many Weber films, to such a degree that her biographer Anthony Slide puzzles over her “fetish.” Fetish is not the right word, but Weber does treat footwear with special care, as another director might treat a locket, or cigarettes, or a cross. Shoes seemed to have been part of her personal symbology, a shortcut to a feeling of loss. She was furious when censors removed a shot of a dead baby’s shoes from Hop, the Devil’s Brew (1916). The film is about a mother so devastated by the death of her child that she becomes addicted to opium. Her husband, a customs inspector, is responsible for confiscating opium shipments from china; one day, he finds his wife huddled among the addicts in an opium den. The shot of the baby shoes was pivotal, Weber argued, to establishing the mother’s suffering and furnishing an explanation for her addiction, but this was precisely the censor’s problem: Weber was treating addiction not as a failure of self-control, but as a consequence of grief.

Still from Shoes, 1916

Still from Shoes, 1916

The state of the shoes in Shoes seems to refer to the loss of Eva’s virginity, but there’s also a more basic reading: Weber is outraged that a functional necessity has become too expensive for a working girl’s income. Another Weber film juxtaposes the poverty of a theologian’s family with their neighbors’ wealth. Weber treats the neighbors with disdain, taking pains to show the ostentation of their car and the excess of their meals. It’s no surprise when she explains that they got rich by selling shoes, priced, she reports, at “$18 a pair!”

Critics treated Weber’s attention to detail as a feminine quirk. They would marvel at her dedication to representing the texture of real life, but it was a cursory wonder, the kind that emphasizes the hours spent. Her approach was sometimes used to imply that she was a filmmaker of small ambition: “obsessed with little things”; her films “infected with the disease of detail.” A review of The Blot (1921) likewise accused Weber of smothering her subject matter “under a mass of plausible but unnecessary detail,” while another sniffed that there was something improper in Weber’s fixation on domestic life, akin to airing dirty laundry. “Many of the scenes are exceedingly painful,” this critic wrote, “and a few seem to invade the privacy of domestic life with unnecessary frankness.”

It is true that affection for domestic objects is Weber’s hallmark. Her films usually take place in homes, with many scenes set in the kitchen. She lingers on frayed rugs, buttons, wooden stools and tea service. Mushrooms are served in folded-parchment paper packets, and potatoes spooned onto chipped enamel plates. Her pacing is slow enough that the mood of a room registers as a presence. A critic observed in 1919, “When [Weber] shows a boudoir scene it is not an accumulation of papier-mâché props . . . she pictures the place as it actually is.”

“Nothing suggests business,” noted the visitor with pleasure. Weber’s habit was to keep the front door ajar.

Weber liked to call her independent studio—so unlike any other in Hollywood—“My Old Homestead.” it was situated in a Southern-style mansion on Santa Monica Boulevard near Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles. Studios were moving to lots during the late teens and early twenties, but Weber insisted on shooting domestic scenes in actual domestic interiors, with the assistance of enormous portable batteries and special lights. A visitor to Lois Weber productions remembered it as a studio like no other, outfitted with rockers, pillows and wide couches. There was a tennis court for staff, and the surrounding acres were landscaped with lemon and loquat trees, jasmine shrubs, and birds of paradise. “Nothing suggests business,” noted the visitor with pleasure. Weber’s habit was to keep the front door ajar.

Helped by the critic André Bazin, cinematic realism would eventually acquire a respected reputation. Writing in 1948, Bazin praised the Italian neorealists of the 1940s for their “revolutionary humanism.” “They never forget that the world is,” he wrote admiringly. Films with a documentary quality—“a perfect and natural adherence to actuality”—left Bazin refreshed, feeling the “urge to change the order of things.” Realism became a celebrated aesthetic, and even a political mode of filmmaking.

Bazin, however, was too late for Weber. he never referred to her work, as much of it had already been long forgotten. As for Weber’s contemporary critics, they noticed her fidelity to domestic detail, but failed to connect it to her true-to-life characters and their true-to-life dilemmas. Insightful criticism might have provided Weber with support and cover for a still more ambitious cinematic vision; without it, she simply insisted that she made the kind of films that people wanted to see: “the time can’t be far off,” she predicted, “when the man or woman who comes to a picture is going to look about and realize that no such perfect creature as the time-honored hero exists either on this earth below or the heaven above. And they are going to even more willingly pay their nickels and their dimes to see a flesh-and-blood person whom they can recognize out of their own experience.” Her forecast turned out wrong; Weber and Hollywood were parting ways.

Lois Weber at her typewriter, 1926

Lois Weber at her typewriter, 1926

*

Weber’s obituary remembered her not as a director, but as “Lois Weber, Movie Star-Maker.” By the end of her life, her reputation as a talent scout had eclipsed her work as a filmmaker. She truly did help many women, and some men, to stardom—Mary MacLaren, Lenore Coffee, Marion Orth, Jeanie Macpherson, John Ford, Henry Hathaway—but she was not a “star finder” in the conventional sense. By dint of time and energy, she nurtured a system of patronage that brought women into the industry and moved them up the ranks. The invisible gears behind career advancement are mentor relationships, as people in power help their likenesses ascend. Rarely do these networks favor women, and even more rarely does a woman become powerful enough to anchor her own. Weber did.

On Friday nights she often had drinks with Hollywood’s female elites. These soirées—the press called them “hen parties”—took place at Frances Marion’s house. Marion was a prolific screenwriter who transitioned from silents to sound without a bump and saw well over one hundred of her screenplays produced. In the thirties, she was making some $17,000 per week. Screenwriters were writers for hire, paid by the week or day, and rarely informed of the destiny of their work. Marion, on the other hand, was allowed to shepherd her projects through production and often presided on set. Her first job, however, was as a jack-of-all-trades for Lois Weber. When the two women met, Weber told Marion, “I have a broad wing, would you like to come under its protection?”

Sasha Archibald

Sasha Archibald's essays have appeared in magazines including Cabinet, The Point, The Believer, East of Borneo, Smithsonian.com, Rhizome, Three Letter Words, Modern Painters, X-TRA, Longform, Los Angeles Review of Books, and in many books and exhibition catalogues. In 2019, her work garnered a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Art Writers Workshop mentorship with Holland Cotter, co-chief art critic of The New York Times. She is an editor-at-large at Cabinet magazine. Archibald works as a curator and arts worker, most recently as Director of Public Programs at Clockshop in Los Angeles. She teaches critical studies and art criticism at Pacific Northwest College of the Arts and Portland State University.