When the Government Tried (and Failed) to Come for a Japanese-American Journalist

From the Late James Omura's Memoir of Internment and Repression

Wyoming signified the Teton Peaks, etched against the northeastern horizon—austere, imposing, and in a fashion awe-inspiring. It evoked the raw and fabulous Yellowstone; the noted chronicler of Western lore, Zane Grey, and his absorbing literary accounts of the Jackson Hole gang of outlaws, of gunslingers, of frontier marshals, and of cowboys; and Cheyenne, the state’s largest metropolis on the eastern plains, a frontier outpost often mentioned in stories of the Old West. That was in my boyhood years in the late 1920s while residing in the southeastern Idaho rail center of Pocatello. This concept of Wyoming abruptly changed in the spring of 1942 when the Corps of Engineers set to work to establish a concentration camp in the sage land of Park County, 11 miles southwest of the city of Powell.

The government named the compound Heart Mountain Relocation Center, inspired by the peak that loomed in the background, but there was no mistaking its concentration camp entrapments—watchtowers mounted with powerful searchlights, sentinels perched at the ready with rifles under orders to shoot any internee approaching within five feet of the barbed wire encircling the compound, and at the entry gate army personnel to monitor egress and ingress. All of this spoke of a prison camp. Heart Mountain housed nearly 11,000 Japanese American inmates from the West Coast, of whom two-thirds were American citizens by birthright. The only legitimate charge that conceivably could be lodged against these people was that of their racial origin. Despite the confinement of more than 2,000 immigrant Japanese, who were aliens by U.S. laws, in Department of Justice internment centers, and the custody of 120,313 in so-called wartime “relocation camps,” not a single prosecutorial case ever arose. Instead, the fundamental precepts of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were twisted and frayed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his administrative minions. In a further attempt to eliminate the Japanese presence in America, the Roosevelt administration resorted to congressional passage of a thinly veiled, hastily conceived denaturalization law. Now whenever Wyoming is mentioned, it conjures up the memory of Heart Mountain and the Fair Play Committee, a courageous and militant citizens’ organization born in captivity.

It is one of the great ironies of our time that the goals the Fair Play Committee sought have been virtually relegated to limbo. It is my belief that this Nisei movement deserves a much better fate. Its policies spoke to the moral conscience of a victimized people and in so doing constituted an integral and historic segment in the story of Japanese in American life. The reason for its obscure nature comes from a deliberate design to obliterate it as an act of shame and dishonor. Its own ethnic leadership has branded it as an evil commission against the wartime Roosevelt administration. However patriotic, it did not demand that a collaborationist leadership should loudly espouse every infringement of constitutional prerogatives by an authoritarian government. But the Japanese American Citizens League chose to run verbal interference for a regressive government and was allowed to serve as a stalking horse for the FDR entourage.

Harassment did not begin with my editorship of the Rocky Shimpo on January 28, 1944, nor did it end with my November 1, 1944, acquittal in the conspiracy trial of the Fair Play Committee steering committee and me. In the fall of 1942 my wife, Caryl, opened a malt and sandwich shop in Denver, Colorado, at 2008 Larimer Street, next door to Harry Osumi’s jewelry shop. The enterprise was well patronized by furloughed internees until a month later, when persistent negative rumors began to circulate against the establishment. The office of the evacuee placement bureau I managed had been moved by then from its original 19th Street address to a mezzanine site on the property of the malt and sandwich shop. I thought it necessary to look into the first rumor and to put it to rest. The investigation identified the source as a driver for the Coca Cola Company. The result of that report was forwarded to the Denver Coca Cola Company. Our report had established that the driver had skipped town. To our dismay, other rumors surfaced periodically and badly damaged patronage. Consequently, in the fall of 1943 Caryl’s Malt & Sandwich Shop was forced to sell out, and it then became Ben’s Place.

In late December 1945 Caryl picked up some revealing information about the damaging rumors in Denver of a few years earlier when she visited Phil Stroupe, the pre-eviction photographer for Current Life magazine, at his commercial studio in San Francisco. Stroupe is said to have stated to her that Nisei agents for Naval Intelligence were planted at Caryl’s Malt & Sandwich Shop to instigate pro-Japan utterances. Furthermore, Stroupe allegedly told Caryl that he had obtained this information from a longtime personal Nisei friend in Naval Intelligence.

“Heart Mountain housed nearly 11,000 Japanese American inmates from the West Coast, of whom two-thirds were American citizens by birthright. The only legitimate charge that conceivably could be lodged against these people was that of their racial origin.”

The erroneous report of the Fort Lupton JACL rally on February 10, 1943, appears to continue to linger. In 1988 two researchers from the Japanese American National Museum based in Los Angeles paid me a visit and briefly alluded to the incident, obviously having picked up some unsavory rumors in the community. Here is the story as I saw it. It all began with my overhearing two activist native Coloradans, Kazumi Miyamoto and Harry Matsunaka, discussing excitedly a JACL dinner in the northern Colorado farm community of Fort Lupton. I requested being taken along and it was agreed upon on the one condition that I not speak out. That promise was given and kept.

However, I was spotted from the head table, and after some consultation each attendee was asked to rise and identify him- or herself. When my turn came, I rose quickly, spoke rapidly and not too clearly, giving the name “James Matsu.” Joe Grant Masaoka at the head table heard it as “James Iwasa.” The members at the head table held another long confab. I was seated two-thirds down at the long table. The person to whom Masaoka refers in his press article sat two chairs closer to the head table. Masaoka’s story was not centered on some unknown attendee, but on me.

Few of us lingered near the long table after the dinner had ended. When an excited verbal ruckus broke out in the back of the auditorium, our group naturally drifted toward the commotion. Loud accusations were being tossed back and forth. Then, totally out of nowhere, Masaoka ended the confrontation with, “We’re coming back with a bigger group, Jimmie!” I was standing at the fringe of the group and was not involved. The fireworks had been set off by Miyamoto and Matsunaka, the two activists whom I had accompanied to the rally. I had never formally met Joe Grant Masaoka, but to him I was undoubtedly a target.

Before departing Denver, Masaoka released his press article to the two Denver vernacular presses. The publisher of the Rocky Nippon, Tetsuko Toda, provided me a copy for my information and comment. This was my response:

I have looked over the report written by Joe Masaoka, Director of the Associated Members Division of the National Japanese American Citizens League, on the Buddhist Rally held in Fort Lupton last Sunday evening. I have given particular attention to the following passage:

“In the Open Forum which followed, James Omura directed questions which indicated the lack of unanimity among a certain Nisei population. Masaoka gently rebuked the attitude and lethargy of such lackadaisical groups. The announcement of the volunteering [for military service] of the National Secretary of the JACL [Mike Masaoka] was roundly applauded and was [a] more than adequate answer to would-be carping critics.”

I advised Miss Toda that “in the event this report is printed in full, we would like to request an opportunity to [provide a] rebuttal in the following issue.” The Rocky Nippon did not publish the article, but apparently its rival, the Colorado Times, did. Neither of the Masaokas was a diligent purveyor of the truth.

*

It was 9 pm on June 10, 1943, when two plainclothes men entered Caryl’s Malt & Sandwich shop on Larimer Street. One man locked the door and the other advanced on me. Caryl was cleaning the grill.

“It’s been reported that a pro-Japanese statement was made in this establishment,” he said.

“I don’t know anything about it,” I replied. “I wasn’t here.”

“We know,” the detective acknowledged. “We’re from the United States Attorney’s office.”

“What’s this about?” I asked.

“We’re asking the questions; you just answer them,” he retorted a bit testily.

I kept backing away because he advanced uncomfortably close. I was backed into a back booth above which was a wall phone. When I tried to reach the phone, his hands screened me off without making any contact. His too-close proximity was unbearable.

“I have a right to call my attorney,” I said.

But the detective prevented it. At that moment, Caryl made a dash for the private quarters before the second man could block the exit. There then ensued a long verbal sparring duel. No further mention was made of the pro-Japan remarks. I had been told a customer had made such a remark and the businesspeople on Larimer Street had alerted us that inquiries were being made in the community. It was only a matter of time before we would be approached directly.

Two hours later, the detective asked to see my Selective Service registration card. He quizzed me about the name and claimed it was registered illegally. Though he prohibited me from use of the phone, he contacted United States attorney Thomas J. Morrissey. It was a long conversation, and after it was over the detective stated he had been instructed to allow me to call my attorney. I therefore dialed Robert McDougal and informed him of the situation. McDougal spoke with Morrissey and later called me back.

“Mr. Morrissey said if you would agree to be in his office at eight in the morning with your wife, he would call his man off.”

“I agree!”

The next morning, June 11, 1943, we were ushered into a long oblong room with a high ceiling. Mr. Morrissey was the only occupant, but I could glimpse an adjoining lighted room. I suspected I was being monitored. I stated to Morrissey that I objected to being “hassled by his flatfoots.” I was still hot under the collar.

“Look here,” Mr. Morrissey declared, “I can have you locked up for 72 hours without any charge at all. I’ve got a good mind to do that!”

The questioning then proceeded. At its conclusion, he explained that he would have to check with my draft board in San Francisco. We were allowed to leave. In the 1980s, under the Freedom of Information Act, I received a copy of this report. It appears my own attorney wrote this report. Special FBI agents were sent out to Seattle and San Francisco. In Seattle the agent drew a blank. In San Francisco an agent so infuriated Phil Stroupe that he banged a set of Current Life issues on his desk and challenged the agent to find any pro-Japan articles in it. He told Caryl in December 1945 that the agent picked out an article about discrimination in the Red Cross and one other on eviction as being somewhat pro-Japan. These were struck out by Nat J. L. Pieper, the special FBI agent in charge at San Francisco, wrote that no negative report on me had been uncovered. Every Caucasian contact offered sterling references. Agent Sterling F. Tremayne interviewed my brother Casey at Firland Sanatorium, just north of Seattle. Long afterward and during the period I was out on bond, Casey wrote that Tremayne was particularly interested in my reported use of the name “James Iwasa.”

The name “James Iwasa” appeared in the complaint alleging a false registration charge in Selective Service records in San Francisco in 1940. United States attorney Morrissey, in declining to prosecute after extensive investigation, stated the action of his office had been predicated on a complaint from the Japanese American Citizens League.

It surprised me to learn the high degree of status I seemed to have enjoyed among the white community. The “white paper” was so complete of my San Francisco sojourn that I couldn’t have asked for a better set of references. Though the FBI inquiries swirled all around me, I was never directly asked about any legal name. The FBI did ask me about the “James Iwasa” name, which I disclaimed. In the witch-hunt activities of the JACL, I knew I would be a target, and I could feel the pressure. Shortly after the California Street Methodist Church public forum sponsored by the national JACL in March 1943 in Denver (which will be discussed below), I applied to legalize James Matsumoto Omura as my name, feeling it could be the Achilles’ heel in an otherwise unblemished record. It was not difficult to unravel the JACL intent. The Fort Lupton faux pas, the Joe Masaoka obfuscation in the Colorado Times, the preplanned attempt at embarrassment at the California Street Methodist Church public forum, the Mike Masaoka/Minoru Yasui incident at the Denver Japanese Hall—all pointed to dire things to come. This accounted for the legal name change, although it was not on that knowledge that the United States attorney declined to prosecute. There simply was no case.

__________________________________

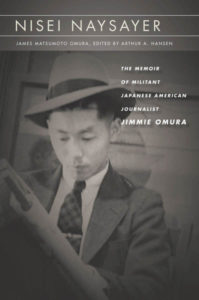

Excerpted from Nisei Naysayer, by James Matsumoto Omura and Arthur A. Hansen, © 2018 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. Published by Stanford University Press. All rights reserved.

James Matsumoto Omura and Arthur Hansen

James Matsumoto Omura (1912–1994) was a newspaper editor and later operated a landscaping business in Denver, Colorado. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Asian American Journalists Association in 1989.

Arthur A. Hansen is Professor Emeritus of History and Asian American Studies at California State University, Fullerton.

Nisei Naysayer is out now from Stanford University Press.