When the French Invaded Hanoi, My Brothers Stayed Behind

They Knew War was Coming and Were Eager to Fight

When war reached my doorstep, I was too little to understand what was going on, but not too little to sense that something terrible was happening and to feel afraid. The experience etched such powerful scenes in my memory that even now I can still see myself as a six-year-old child listening to the sound of gunfire, being yanked from my game and rushed to the shelter, imitating my adult relatives and raising my arms in surrender to the French, fleeing the smoldering ancestral village transported in a wicker basket, and looking back and seeing the severed head on the roof.

That day in 1947, my family and I lived through one of the most frightening experiences of our lives. My family had evacuated to Van Dinh weeks before, after my father had decided fighting was imminent. We packed up and left for what he believed would be a short stay. He thought that it would take the French just a few days to overcome the fledgling Viet Minh force in Hanoi; then things would be calm again, and we would be able to return home. My brothers Giu and Xuong did not go with us. They knew that there was going to be war and were eager to be part of the action. At this time, two of my sisters could not be evacuated—my older sister Mao and my younger sister Cuc, who was in the hospital with chronic osteomyelitis—so my parents agreed to let Giu and Xuong stay in Hanoi, in part to look after my sisters.

Before leaving, my parents gave my two brothers enough rice and money to last until we returned. If my parents could have guessed what would happen later, they would have ordered them to come along. After we departed, many neighbors also left, part of the first wave of refugees out of the city, and the streets became deserted. At night, my brothers felt exposed and uneasy, afraid of the robbers that were roaming in the increasingly empty city. For protection, Giu strung wire across the windows and doors.When a family next door that had not evacuated invited them to move in, my brothers eagerly accepted.

On the morning of December 19, 1946, the French issued an ultimatum, ordering the Viet Minh to throw down their arms and stop all preparations for war. The Viet Minh rejected it and, from their secret radio station hidden in a cave outside Hanoi, issued a call for national resistance with a succinct message: “The Fatherland is in danger. The hour of fighting has arrived. Let’s sacrifice ourselves and fight till the last drop of blood. Let’s annihilate the French colonialists! Let’s fight to the finish!” The hour of war was secretly scheduled for eight o’clock that evening. That night, Vietnamese workers sabotaged the power station near the central lake. Suddenly, the whole city went dark. This was the signal for the Viet Minh offensive. Their few pieces of artillery opened fire on French positions, and scattered attacks against pockets of French control erupted. From his bed in a house near the outskirts of Hanoi, waiting for the evacuation to the Viet Minh base, my brother-in-law Hau listened to the gunfire and felt elated. Finally, the hour for Vietnam to wash away its humiliation had arrived, he thought. On that same night, fighting broke out in other cities throughout the country, marking the start of the national resistance war.

After the initial attacks in Hanoi, the Viet Minh told the residents to evacuate, and people began to pour out of the city. In all, about 100,000 people—two-thirds of the population—fled, streaming into the countryside to look for shelter. The day after the outbreak of war, on December 20, Ho Chi Minh issued an appeal for national resistance, calling for sacrifices and predicting a long and hard struggle with certain victory at the end. Vietnamese responded en masse to this call to arms. All over the country hundreds of thousands of people pulled up stakes to trek into the Viet Minh zone to be part of the war against the French, and youths volunteered in droves for the army. The flame of nationalism never burned as bright in the hearts of the people, and the Vietnamese never united as strongly behind the Viet Minh as in those first days and months of the resistance.

At the outset of hostilities, the French moved quickly to take over key Viet Minh government agencies in Hanoi, but when they finally stormed the buildings, they found out that most of the Viet Minh leadership had quietly slipped away. The French expected to seal off and destroy Viet Minh forces in Hanoi within 24 hours, and then—with new reinforcements slated to arrive at the end of the year—push into the countryside to pacify Tonkin. But like the U.S. Marines that would take over the city of Hue in the 1968 Tet Offensive, the French discovered how slow and arduous house-to-house fighting could be. Even after they managed to secure an area of town, scattered sniper fire and occasional ambushes continued to harass them. The battle for Hanoi lasted 60 days, a lot longer than the French had anticipated. The Viet Minh strategy of pinning down their adversaries worked, and bought them the time they needed to move their government and troops into their mountain base.

The day after hostilities flared up, fighting reached my neighborhood. Suddenly, being in the militia was no longer just fun and games for my brothers Giu and Xuong, no longer just marches and drills with spears. Their militia unit buried its first casualty when French snipers shot a squad leader as he climbed up a flagpole to display the Viet Minh banner. Right after that incident, a messenger arrived with the news that French troops stationed in the Lanessan Hospital near our house were getting ready for an assault, supported with lots of tanks.The messenger told the militia unit to withdraw that night, under the cover of darkness. But the French attack came before nightfall, with airplanes and tanks strafing the Viet Minh troops’ barracks near the dike. After the bombardment, French paratroopers advanced into the neighborhood from three directions, with fierce shouts of “En avant!” There was no return fire from the Viet Minh regulars, who had secretly and hastily withdrawn, leaving the militiamen to fend for themselves.

The swiftness of the French arrival caught Giu and Xuong by surprise. When they heard the footsteps of French soldiers approaching, my brothers at least had the presence of mind to toss their incriminating spears over the wall. If they had been caught with these weapons, they would have been shot on the spot as Viet Minh suspects. Then Giu ran and hid under the stairwell, while Xuong rushed out the back with Mao in tow to hide in the garden. The French found them cowering in a corner of the yard, and led them away. They put Xuong in jail, and when they realized that Mao was crazy, let her go. She wandered in the street until an acquaintance spotted her and took her to live with his family, sending her back home when my parents returned to Hanoi. Inexplicably, the soldiers did not enter the house, and Giu and the neighbor’s family were spared.

That night, the Viet Minh sneaked back and opened fire on French positions. No damage was done, but the attack angered the French. The next day, they stormed back with German shepherds to search the neighborhood. The streets echoed with the furious barking of the dogs, the crunching of French boots, and the angry voices of the soldiers, who were spoiling for retaliation. The older neighbor suggested to Giu that it would be best for them to come out and surrender, and not wait for the French to come in and shoot them. My brother agreed. When he heard the soldiers at the gate, he came out of hiding and met them. In fluent French, he said to the commander, “I’m a student at the Lycée Albert Sarraut. I haven’t been able to evacuate with my family. My father’s a mandarin.” He thought this string of reassurances might calm the jittery French. The commander listened attentively and scrutinized him. Giu was wearing an old discarded military shirt that my mother had bought for him dirt cheap in an open-air market. But this did not arouse the commander’s suspicion. He seemed persuaded. Suddenly, a half-naked French soldier rushed in. He looked at Giu, took him for a Viet Minh, and angrily swung his rifle butt at my brother’s temple with all his strength. The commander raised his arm in the nick of time to ward off the blow, and instead of splitting Giu’s skull—and perhaps killing or at least blinding him—the rifle butt landed just above his left eyebrow, cutting him and leaving a permanent scar.

The French took Giu and the neighbor by truck to the Lanessan Hospital, then serving as a temporary detention center. From then on until his release, Giu, like the other prisoners, was at the mercy of their captors, and could live or die at their whim. Prisoners could be alive one moment and dead the next—shot for being Viet Minh suspects or simply executed in revenge for those killed in Viet Minh attacks.

__________________________________

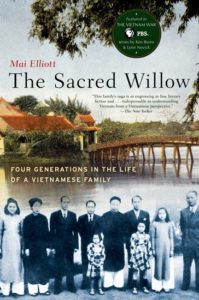

From The Sacred Willow: Four Generations in the Life of a Vietnamese Family. Used with permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Mai Elliott.

Mai Elliott

Mai Elliott was born and raised in Vietnam and attended Georgetown University on a scholarship. She lived in Vietnam again from 1963 to 1968 and worked for the Rand Corporation interviewing Viet Cong prisoners of war. She returned to the U.S. in 1968 and now lives in California.