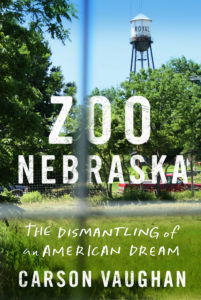

When the Animals Bust Out of a Small Town Zoo

Trouble in Royal, Nebraska, Population 81

The wind bolted for open doors and whistled through windowpanes. It stole crumpled Powerball slips

from the gutters—feed sacks and greasy napkins and leftover baling twine. It rolled cigarette butts down Main Street. It whipped the dust—fine and buff—from the hoods of worn-out pickup trucks. September 10, 2005. A typical day in Neligh, Nebraska. The sun hammered the plastic sign above Daddy’s Cafe, blurred the candy stripes racing up the tin exterior. Inside, cafeteria silverware clanked on ceramic dishes while coffee burned on the warmer. Occasional gales shook the glass like a Freightliner passing at full speed. An American flag hung prominently from the wall beside a shadow box of country trinkets and antiques.

Brian Detlefsen and Darrell Hamilton sat at a table near the center of the room. They were an odd couple: Detlefsen a square-jawed, rosy-cheeked, 27-year-old state trooper and Hamilton a pudgy, slow-moving, 50-year-old county sheriff. One in blue, the other brown, both easygoing and optimistic. They placed their hats on the table and surveyed the room: familiar faces all around. Detlefsen grew up chasing the goats around his parents’ farm behind the Dodge dealership on the west edge of town. He had wanted to be a cop or a rodeo clown.

“My mom said she would disown me if I became a rodeo clown, so I became a cop.”

He’d enrolled at Wayne State, a small college wrestled from a cornfield 60 miles east. He studied criminal justice with “a little bit of psychology thrown in there,” he says. After graduation, he spent six months training with the Nebraska State Patrol in Lincoln, which then stationed him with the Carrier Enforcement Division back in his hometown, weighing and inspecting semitrucks with a portable scale. And two years after that, he’d transferred to the Field Services Division, where the job aligned more with his original vision: racing to the scene, issuing citations, clocking highway travelers, grabbing lunch with the county sheriff. He was hardly one to brag, but the whole process had seemed almost too smooth. All the patrolmen he’d known as a kid had been old guys with a mustache and a gut, and here he’d come, fresh out of the academy at just 22 years old, already back home with his boots on the ground.

Their meals had just arrived when the sheriff’s pager lit up. Animals loose at Royal Zoo. Need 10-49. Traffic control. Hamilton sighed and set his pager back on the table. Royal was a 20-minute drive. Detlefsen kept eating. Neither sat up. Neither rushed out the door. A loose goat, most likely. Potential roadkill, or soon to be. Maybe the donkey slipped its pen. Hardly a pressing case either way. Hamilton took another bite, wiped his mouth, and drew a deep breath.

“Well,” he said, shaking the table as he stood.

“Let me know,” Detlefsen replied.

Detlefsen watched as Hamilton replaced his hat and stepped into the sunlight, wind rushing in through the closing door. He hadn’t thought about the zoo in years. He used to visit when he was just a kid—they all did—back when the zoo was still a trailer home off the highway, a chimpanzee in a corncrib, a few petting goats. Not so different from the farm, really, save for Reuben, “that stinker throwing his feces.”

Detlefsen sat there sweating in his patrol vehicle, watching the wildness before him, this macabre circus, an active shooter and two bleeding chimpanzees.

Detlefsen and his family would make a day of the trip: first the zoo, then Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park, the trout hatchery, sometimes the Gavins Point Dam up north along the Missouri. He’d lost track of the zoo over the years, grown out of it, maybe, though by the time he returned from Wayne, Zoo Nebraska had grown up, too, with tigers and lions now stalking the cages and Reuben’s three new roommates: Ripley, Tyler, and Jimmy Joe. Still a novelty, perhaps, but no longer a joke. A few minutes later, as Detlefsen eyed the last fries on his plate, dispatch called.

“They need you up there now. They need guns.”

The cab of the cruiser was static and warm. Detlefsen cracked the window as he backed onto Main

Street and steered toward the highway, past the redbrick courthouse with the golden antelope perched on top. He sped north, cutting through a vast sea of corn, green and undulating, past crooked telephone poles and drooping lines, past long, thick rows of shelterbelts dividing one field, one property, one farmhouse from the next, the road so familiar after all these years he could practically drive it blind, every dip and swell expected. The sky offered blue and more blue without a single cloud mooring on the horizon, nothing to count, nothing to question. Just endless blue, and a yellow streak of bug juice glued to the windshield. He hadn’t even turned on his lights. I’ll get there, he thought, when I get there.

By the time he met the juncture at Highway 20 and turned west, he could hardly remember the last 15 miles, as if he’d simply materialized at the intersection where the Yum Yum Shack used to sling burgers and swirl soft-serve ice cream in the dog days of summer. Three miles more and the Royal water tower crested above the trees, a giant tin can on stilts, silver and blinding in the sun. Irrigation pipe scalloped above corn tassels like the bones of a sea serpent, and a yellow haze drifted across the road. Detlefsen kept his eyes peeled for an escaped goat or an injured animal on the shoulder as he passed the cemetery and its white vinyl fence, the zoo just a quarter mile ahead.

But the ditches were clean. The road was open. Only the sheriff’s vehicle hinted at distress. Detlefsen stalled briefly behind the mileage sign for Plainview and Sioux City before slowly pulling closer to the zoo’s front gate, shaded by a row of trees bowing in the wind. Detlefsen flipped on his dashcam. The radio crackled in the cab, the equipment jostling with every divot in the dry dirt parking lot, as Arvin Brandt, an off-duty county patrolman, drove past him.

“Is Arvin upset or what’s the story, four-seven-eight?”

“I just got here,” Detlefsen replied.

“Ten-nine?”

“I just got here when Arvin was pulling out.”

Detlefsen noticed a black mass in his periphery, slowly moving on all fours outside the old church-

turned-activity-center, its back flat as a two-by-four, rump naked and pale. A smaller one shambled around the corner. A white golf cart emerged from the tree line and sputtered toward the animals, a hulking man behind the wheel, his arm outstretched, revolver in hand. Two shots rang out, but the animals didn’t stop and the golf cart didn’t slow down, and State Trooper Brian Detlefsen, badge number 478, stared in utter disbelief, hands clutching the wheel tight, as the bigger chimp galloped down the fence line at full speed, limbs a blur, a sci-fi-cum-Western, a shootout at the church. This wasn’t the petting zoo he remembered. They hadn’t covered this at the academy.

“It wasn’t like I could just get out and tackle this thing,” he says. “There ain’t no way you’re going to get out and talk to a chimpanzee and say, ‘Hey, how’s your day going?’”

So Detlefsen sat there sweating in his patrol vehicle, watching the wildness before him, this macabre circus, an active shooter and two bleeding chimpanzees—maybe more—blitzed on a double shot of adrenaline and chase. It was the most surreal thing he’d ever seen, on duty or off. Behind him, a semitruck barreled down Highway 20, oblivious to the mayhem. Ahead, a shriek lifted from the trees and carried across the yard, a shriek so wild, so primal it seemed to rise from within, a shriek so desperate he would remember that precise pitch for the rest of his life.

The bigger chimp kept running, kicking up dust, until he mounted a bank of cinder blocks in a single fluid skip and rested in the shade of a lone tree on the zoo’s eastern fence line. The whole tree warped and yawed as if battered by a tropical storm. And just as two pickup trucks thundered past him and punched into the parking lot, elbows hanging out the windows, his cell phone rang out with the digital cannon fire of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. His wife was calling.

“Hello?”

“I’m telling you . . . where are you at?”

“Royal—why?”

“Our washer is flooding again.”

“Okay, shut it off. I . . . I’ve got a situation here. I’ve got to go.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream by Carson Vaughan. © 2019 Published by Little A, April 1, 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Carson Vaughan

Carson Vaughan is a freelance journalist from Nebraska who writes frequently about the Great Plains. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian, The Paris Review Daily, Outside, Pacific Standard, Travel + Leisure, The Atlantic, VICE, Runner's World, In These Times, and more. Zoo Nebraska is his first book.