When the American Dream Goes Sideways; Or, Why I Am Not Like JD Vance

Georgiann Davis Offers Some Lessons From A Middle School Dropout

“It’s in right now to be with an Indian girl,” Mom quipped after seeing Vice President JD Vance and his wife, Usha, flash across the Fox News screen she was watching.

“Please,” I begged, “please don’t ever compare us to Vance.”

“But that book he wrote—it’s like yours.”

As much as I hate to admit it, Mom isn’t entirely wrong. There are a few similarities between my story and Vance’s. We’re both white. And as she likes to remind me, we’re both partnered with Indian women. We both had turbulent childhoods, shaped by familial trauma and fueled by addiction—alcohol, drugs, all of it. And we both used education to move beyond lives we didn’t want to live.

But that’s where our similarities end.

The way Vance tells his story reinforces the myth of the American Dream. The way I tell mine challenges it.

I don’t just mean the obvious differences—that I’m a queer intersex woman partnered with another woman, that I live in a modest home in Albuquerque rather than the Vice President’s residence, or that I’ve never set foot inside an Ivy League school.

I mean how we make sense of how we got here. The way Vance tells his story reinforces the myth of the American Dream. The way I tell mine challenges it.

The idea that anyone can succeed through hard work and ambition may hold true for some white people like Vance and me. But for everyone else, especially people of color, it is at best misleading and at worst dangerous.

For the first ten years of my life, I grew up in a three-bedroom apartment not far from Chicago’s Midway Airport, in a racially diverse working-class neighborhood. But as more Black and Brown families moved in, my parents—like many of our white neighbors—decided to leave. They didn’t want my brother and me going to school with Black and Brown kids, so they moved us to the suburbs in what sociologists call “white flight.”

There, we lived in a sprawling house we couldn’t afford, filled the garage with luxury cars we couldn’t keep, and charged vacations and fur coats to credit cards. On the surface, we looked well-off. In reality, we were drowning in debt.

I made it halfway through seventh grade before dropping out, but I still ended up a college professor—having never graduated from middle school or high school.

After dropping out of middle school, I worked full time in my family’s ice cream business for several years, until our stores were shut down. When I was sixteen, I landed a clerical hospital job—not because I aced an interview, but because my aunt worked there and “put in a good word,” helping me gain access to opportunities. That job eventually paid me $13.70 an hour, well above minimum wage in 1996, despite my being a seventh-grade dropout. This is how networks work. As a white teenager, I could piggyback on my aunt’s race and class position to access opportunities.

Beyond the paycheck, the job gave me cultural capital that made further advancement possible. I learned how professionals spoke, dressed, and interacted. I still remember a radiologist correcting me after I said, “No, I ain’t found it yet,” when referring to a missing medical record. Elitist or not, it was a free English lesson. That same doctor later told me I was “too smart” for my clerical job and that I belonged in college. Would he have said the same thing to a Black woman? Probably not.

But his comment was right on time. I had just visited a friend on her college campus. She was in her first semester of college and wanted to show me around. I stayed with her and her roommate in their small dorm room, sleeping on the floor between their lofted beds. Being amidst the buzz of students reading under trees, playing ball in the courtyard, and simply socializing made me envy their lives, which were so very different from mine.

This is it, I thought. This is what I want to do. I decided then that I would figure out what I needed to do to get my GED and pursue this dream. I started searching the internet and learned that the test was offered at the local community college, but I needed to be at least 18 to take it. Illinois, like many other states, instituted this requirement to discourage youth from using the GED as a shortcut to drop out of traditional schooling. In less than a year, I could take the test, so I went to a bookstore, purchased a GED prep book, and vowed to work through it so I could sit for the test as soon as I turned 18.

I passed the GED on my first attempt, twelve days after my 18th birthday. As a middle school dropout, I was shocked—I assumed all of my studying had paid off. At the time, I didn’t realize that the GED doesn’t actually measure mastery of high school material. Like other standardized tests, it more often reflects the influence of race and class than a person’s true ability.

This bias plays out in GED performance. Data from the American Council on Education show that while only 60% of people who sit for the GED exam pass, those who succeed are disproportionately white.

When white people talk about how we “made it,” we must also acknowledge that whiteness is an invisible and built-in advantage in how we achieve success.

Passing the GED was just the first step that made college a possibility. But community college isn’t exactly the best route to a four-year degree. A 2024 report from the Community College Resource Center revealed that about 80% of community college students wish to transfer to a four-year college or university eventually, but only a third actually do. And of those who transfer, roughly one out of two never earn a bachelor’s degree. These rates are far lower for Black students, older students, and low-income students. As a community college student reading these statistics, I was discouraged—and quite frankly, scared.

But I was mentored by professors who wouldn’t let me fall behind. They gave my papers more attention than the papers of my peers, encouraged me to apply for scholarships and awards, and most of all, believed in me. Their mentorship gave me confidence to keep going. But would they have invested in me the same way if I weren’t white? Research suggests maybe not. A Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey found that 72% of white graduates reported being mentored by professors, compared to just 47% of minority graduates. That gap shapes performance, career opportunities, and confidence—and propelled me into a sociology doctoral program and eventually an award-winning academic career bridging my life as an intersex person with a sociocultural research program on understanding how intersex is experienced and contested in contemporary U.S. society.

Education was a vehicle for change—but that’s not the full story. While education can open doors, opportunities are undeniably easier to access for those who are white.

On my journey from dropout to professor, I had support at every turn—professors, supervisors, and even an aunt. My hard work and ambition mattered, yes. But so did my whiteness, which made navigating these opportunities smoother. It didn’t erase my struggles, but it amplified my efforts and opened doors others never see.

This acknowledgment of white privilege is what Vance leaves out of his story of upward mobility.

And leaving it out is not just inaccurate—it’s unfair to Black and Brown people who work just as hard, if not harder, but face barriers whiteness shields us from.

I remember when I first shared my story publicly. A white university colleague with a GED and PhD thanked me and shared her own journey. I felt solidarity. But as more white colleagues opened up about similar trajectories, I began to see the pattern which as a sociologist I’m trained to do. Stories like ours are far more common for white people than for people of color.

When white people talk about how we “made it,” we must also acknowledge that whiteness is an invisible and built-in advantage in how we achieve success. Without that truth, the American Dream is not just a myth—it’s a lie.

__________________________________

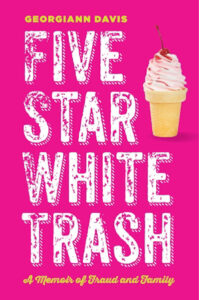

Five Star White Trash: A Memoir of Fraud and Family by Georgiann Davis is available from New York University Press.

Georgiann Davis

Georgiann Davis is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. She is the author of Contesting Intersex: The Dubious Diagnosis.