When Stephen King is Your Father, the World is Full of Monsters

Joe Hill on Standing in the Shadow (and Light) of His Famous Dad

We had a new monster every night.

I had this book I loved, Bring on the Bad Guys. It was a big, chunky paperback collection of comic-book stories, and as you might guess from the title, it wasn’t much concerned with heroes. It was instead an anthology of tales about the worst of the worst, vile psychopaths with names like The Abomination and faces to match.

My dad had to read that book to me every night. He didn’t have a choice. It was one of these Scheherazade-type deals. If he didn’t read to me, I wouldn’t stay in bed. I’d slip out from under my Empire Strikes Back quilt and roam the house in my Spider-Man Underoos, soggy thumb in my mouth and my filthy comfort blanket tossed over one shoulder. I could roam all night if the mood took me. My father had to keep reading until my eyes were barely open, and even then, he could only escape by saying he was going to step out for a smoke and he’d be right back.

I loved the subhumans in Bring on the Bad Guys: demented creatures who shrieked unreasonable demands, raged when they didn’t get their way, ate with their hands, and yearned to bite their enemies. Of course I loved them. I was six. We had a lot in common.

My dad read me these stories, his fingertip moving from panel to panel so my weary gaze could follow the action. If you asked me what Captain America sounded like, I could’ve told you: he sounded like my dad. So did the Dread Dormammu. So did Sue Richards, the Invisible Woman—she sounded like my dad doing a girl’s voice.

They were all my dad, every one of them.

Most sons fall into one of two groups.

There’s the boy who looks upon his father and thinks, I hate that son of a bitch, and I swear to God I’m never going to be anything like him. Then there’s the boy who aspires to be like his father: to be as free, and as kind, and as comfortable in his own skin. A kid like that isn’t afraid he’s going to resemble his dad in word and action. He’s afraid he won’t measure up.

It seems to me that the first kind of son is the one most truly lost in his father’s shadow. On the surface that probably seems counterintuitive. After all, here’s a dude who looked at Papa and decided to run as far and as fast as he could in the other direction. How much distance do you have to put between yourself and your old man before you’re finally free?

The father, in truth, doesn’t throw a shadow at all. He becomes instead a source of illumination, a means to see the territory ahead a little more clearly.

And yet at every crossroads in his life, our guy finds his father standing right behind him: on the first date, at the wedding, on the job interview. Every choice must be weighed against Dad’s example, so our guy knows to do the opposite . . . and in this way a bad relationship goes on and on, even if father and son haven’t spoken in years. All that running and the guy never gets anywhere.

The second kid, he hears that John Donne quote—We’re scarce our fathers’ shadows cast at noon—and nods and thinks, Ah, shit, ain’t that the truth? He’s been lucky—terribly, unfairly, stupidly lucky. He’s free to be his own man, because his father was. The father, in truth, doesn’t throw a shadow at all. He becomes instead a source of illumination, a means to see the territory ahead a little more clearly and find one’s own particular path.

I try to remember how lucky I’ve been.

Nowadays we take it for granted that if we love a movie, we can see it again. You’ll catch it on Netflix or buy it on iTunes or splurge for the DVD box set with all the video extras.

But up until about 1980, if you saw a film in the theater, you probably never saw it a second time, unless it turned up on TV. You mostly rewatched pictures only in your memory—a treacherous, insubstantial format, although not entirely lacking in virtues. A fair number of films look best when seen in blurry memory.

When I was ten, my father brought home a Laserdisc machine, forerunner of the modern DVD player. He had also purchased three films: Jaws, Duel, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The movies came on these enormous, shimmering plates—they faintly resembled the lethal Frisbees that Jeff Bridges slung around in Tron. Each brilliant, iridescent platter had 20 minutes of video on each side. When a 20-minute segment ended, my dad would have to get up and flip it over.

All that summer we watched Jaws, and Duel, and Close Encounters, again and again. Discs got mixed up: We’d watch 20 minutes of Richard Dreyfus scrabbling up the dusty slopes of Devil’s Tower to reach the alien lights in the sky, then we’d watch 20 minutes of Robert Shaw fighting the shark and getting bitten in half. Ultimately, they became less like distinct narratives and more a single bewildering quilt of story, a patchwork of wild-eyed men clawing to escape relentless predators, looking to the star-filled sky for rescue.

When I went swimming that summer, and dived beneath the surface of the lake, and opened my eyes, I was sure I’d see a great white lunging out of the dark at me. More than once I heard myself screaming underwater. When I wandered into my bedroom, I half expected my toys to spring to antic, supernatural life, powered by the energy radiating from passing UFOs.

And every time I went for a drive with my father, we played Duel. Directed by a barely 20-year-old Steven Spielberg, Duel was about a nebbish everyman in a Plymouth (Dennis Weaver), driving frantically across the California desert, pursued by a nameless, unseen trucker in a roaring Peterbilt tanker. It was (and still is) a sun-blasted work of faux Hitchcock and a chrome-plated showcase for its director’s bottomless potential.

When my dad and I went out for a drive, we liked to pretend the truck was after us. When this imaginary truck hit us from behind, my dad would stomp on the gas to pretend we’d been struck or sideswiped. I’d fling myself around in the passenger seat, screaming. No seat belt, of course. This was maybe 1982, 1983? There’d be a six-pack of beer on the seat between us . . . and when my dad finished one can, the empty went out the window, along with his cigarette.

Eventually the truck would mash us, and my dad would make a screaming-shrieking sound and weave this way and that along the road, to indicate we were dead. He might drive for a full minute with his tongue hanging out and his glasses askew to indicate the truck had schmucked him good. It was always a blast, dying on the road together, the father and the son and the unholy Eighteen-Wheeler of Evil.

*

I had a fear when I started out that people would know I was Stephen King’s son, so I put on a mask and pretended I was someone else. But the stories always told the truth, the true truth. I think good stories always do. The stories I’ve written are all the inevitable product of their creative DNA: Bradbury and Block, Savini and Spielberg, Romero and Fango, Stan Lee and C.S. Lewis, and most of all, Tabitha and Stephen King.

The unhappy creator finds himself in the shadow of other, bigger artists and resents it. But if you’re lucky—and as I’ve already said, I’ve had more than my fair share of luck, and please God, let it hold—those other, bigger artists cast a light for you to find your way.

__________________________________

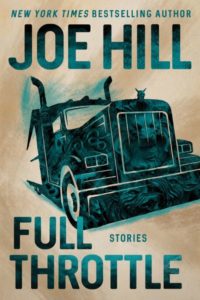

Adapted from Full Throttle by Joe Hill. Copyright Joe Hill 2019, provided courtesy of William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers.

Joe Hill

Joe Hill is the author of the New York Times bestsellers Horns, Heart-Shaped Box, and NOS4A2. He is also the Eisner Award-winning writer of a six-volume comic book series, Locke & Key. He lives in New Hampshire.