When Philip Roth Switched Publishers, Drama Ensued

Ira Nadel Dishes on Life in the Literary 70s

In the year or so between Our Gang (1971) and The Breast (1972), there was an important change for Philip Roth but one that marked a pattern: he switched publishers, something he would continue to do throughout his career. Holt, Rinehart and Winston were more receptive to his demands for larger advances than Random House, which, frankly, found him too expensive. After Portnoy, in fact, Roth never earned back his advances and did not have a bestseller again until The Plot Against America in 2004.

But Roth had a fan in Aaron Asher, who was then an editor at Holt. They had both been at the University of Chicago and likely crossed paths several times in the world of New York publishing, and when Roth began to question his relationship with Random House, initiated by his disappointment with their response to his financial demands as he was completing Our Gang, he began to consider alternatives. A story in the Book of the Month Club Newsletter entitled “The Letting Go of Random House by Philip Roth,” reported the break, although the major players disputed the narrative.

What essentially precipitated the shift was Roth’s disappointment with his agent Candida Donadio. A note dated 7 February 1972 from his lawyer Arthur J. Klein to Epstein announces that Roth’s agency representation is over. Either Klein or his partner, Martin Garbus, will now negotiate and/or advise Roth. Initiating the break with Random House was a disagreement over a new paperback contract with Bantam in October 1971. Garbus was particularly worried that Roth would lose money in the event that a paperback came out prior to six months after the date of a hardback publication.

On 14 April 1972, Roth, now representing himself, detailed submission and royalty requirements for two new books to Epstein and Random House following Our Gang: The Breast and The Great American Novel. If their best offer was acceptable, he would instruct Klein to draw up a contract. Importantly, he wanted each title dealt with separately. If the terms were not acceptable, he would go elsewhere. For The Breast, he seeks an advance of $225,000; for The Great American Novel, $236,250. And for both, he wants to retain all paperback rights. An offer in response on 24 April from Epstein caused Roth to reconsider slightly reduced figures, but for hardback rights only. He was pressured to make a decision in two days.

In the year or so between Our Gang (1971) and The Breast (1972), there was an important change for Philip Roth: he switched publishers, something he would continue to do throughout his career.

Roth declined the counteroffer. To Bennett Cerf of Random House he would explain that despite the failure to reach an agreement, his time with the publishing company had been successful and in almost all respects happy. He admitted that he would miss Epstein’s editorial acumen but believed he would do better financially elsewhere. An exchange with Donald Klopfer was more pointed and personal: he had known Klopfer since meeting him through Styron in Rome in 1960. On 20 May 1972 from Cornwall Bridge, Roth wrote Klopfer:

Your generosity and charm won me over back in Doney’s on the Via Veneta back in 1960, and . . . each time we were together you seemed to me the same kind gentleman one could rely upon and trust… Your presence at Random House was always a comfort to me.

Yours Philip

Klopfer’s response of 27 June, after Roth’s break with Random House, expresses unhappiness with the decision:

Obviously, I was terribly disappointed that we couldn’t come to an understanding with you about your two new books. I received three copies of the Book of the Month Club Report while I was in Rome. I must say that I think Aaron handled it in a dignified and honest way, but I was really irritated by your lawyer’s statement. It showed a complete lack of knowledge of the publishing business, which I am sure is the case. . . I believe that the offer we made was a generous one, and I am sorry you decided to split yourself up as you did—but I do wish you luck. I hope you will sit down and write many more good books, and not become too bewitched by the money.

My best to you.

As always,

[Donald Klopfer]

Roth, slightly offended by the story in the Book of the Month Club Newsletter and Klopfer’s closing phrase, replied on 29 June that he was upset by Garbus’s quoted comments about negotiations and explained to Klopfer that he did not turn to lawyers for advice concerning his two books, nor was he driven entirely by money. Klopfer’s response of 10 July tried to defuse the comment on money and gesture toward a friendship of some sort.

Asher’s own statement about the affair, which preoccupied New York publishing gossip for several weeks (anticipating much later gossip, when Roth signed with Simon and Schuster for hefty fees negotiated by his new agent, Andrew Wylie, in 1989), was professional. Attempting to end rumors that Roth left Random House for Holt only for the money, Asher explained that negotiations with Random House broke down after they could not agree on certain demands from Roth. He would have liked to have stayed, but they couldn’t agree. He and Roth had known each other for a dozen years (he, too, graduated the University of Chicago, with a BA in 1949 and an MA in 1952), so it was almost natural that Roth thought of Holt, which quickly met his demands. But he would have gone elsewhere if necessary. He did not auction his work, Asher emphasized.

Garbus, as quoted in the Book of the Month Club Newsletter, said the new publisher had only the hardcover rights; Roth had complete control over the paperback rights and all other rights, which is what he wanted in the first instance (although no mention of the higher advance was cited). The money is in the paperback business, Garbus went on to say, “so why shouldn’t the writer get his fair share?” These are likely the remarks Roth was uncomfortable with. Ironically, perhaps, My Life as a Man was dedicated to both Aaron Asher and Jason Epstein, in that order, which is itself telling.

Attempting to end rumors that Roth left Random House for Holt only for the money, Asher explained that negotiations with Random House broke down after they could not agree on certain demands from Roth.

An incident from this period confirms Roth’s growing pleasure with what his friend, the novelist Alan Lelchuk, called “American mischief,” the title of his 1973 novel. It also shows how he defended young writers when bullied or abused. The incident occurred in late September 1972, brought about by a scene in Lelchuk’s forthcoming novel concerning the fictional murder of Norman Mailer—shot in the ass with his pants down in his hotel room. The title of the draft account of the encounter is “The Godfather of the Literary World & a Young Offender.”

It began with Roger Straus, Lelchuk’s publisher at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, receiving a telegram from Mailer asking to meet to discuss a reported scene in Lelchuk’s forthcoming novel where he is assassinated. Straus contacted Cy Rembar, Mailer’s lawyer, to negotiate, but Mailer persisted with his complaint, although FSG’s lawyers felt it was “Ok” to use Mailer’s name since he was a public figure. Lelchuk removed the names of other intellectual figures but wanted to keep the high-profile Mailer. Indeed, he felt betrayed by FSG for even acknowledging Mailer’s request. In the novel, the protagonist, Lenny Pincus, reading Nietzsche at Widener Library at Harvard—Mailer was to lecture at the school the next day—follows the argument of Mailer’s White Negro, that he must knock off the arrogant, pushy writer, which is also knocking off the institution of literature. In questions after his fictional lecture, Mailer exclaims, “Show me a red-blooded American boy who reads books and I’ll show you a potential murderer.” Lenny Pincus fulfills that claim.

A meeting was scheduled, where Mailer’s lawyer, Rembar (who had successfully won a case for Grove Press suing the U.S. Post Office for confiscating copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover) suggested that Lelchuk bring Roth as a second. Roth was invited partly because he wrote a critical preview of the novel in Esquire from which Mailer supposedly learned of the scene, although a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Robert Lucid, who was planning an anthology of fictional portraits of real authors, had also written to reveal the scene to Mailer. Roth was an artful ally not only of Lelchuk but of Roger Straus: he knew of Straus’s anger in 1970 over the slight to Portnoy’s Complaint when it failed to win the National Book Award. Within a year Roth would join Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In a parallel incident at the time, Roth contradicted a false report of his death.

One fear and reason for the Lelchuk-Mailer meeting, and hoped-for removal of the murder scene, was that it might encourage real assassins to attack Mailer. Lelchuk’s own lawyer would accompany him since his interest was literary, “not pugilistic and I wanted the referee to be a legal one.” Lelchuk had prepared for the meeting by reading Mailer on censorship in his Presidential Papers and Advertisements for Myself. Rembar had even written an introduction to a book on obscenity and censorship, so Lelchuk was convinced that ethically and legally he was right in his literary murder of Mailer, shot by a radical in the buttocks with his pants down.

The meeting occurred on 29 September 1972 on the thirty-sixth floor of the New York law office of Lelchuk’s lawyer, Martin Garbus. Roth, Lelchuk, Mailer, Robert Giroux (an FSG editor), Georges Borchardt (Lelchuk’s agent), and others were present. Mailer was in a suit but with no tie and his shirt open and “wild hair.” Lelchuk, defending his first book, wore a sport coat and tie and carried a briefcase. An account of the gathering published in the New York Times of 18 October reversed the dress, with Mailer in a pin-striped suit and Lelchuk the bohemian and “bearded bachelor.” (The thirty- four-year-old Lelchuk, then teaching at Brandeis, was, in fact, bearded at the time.) At Roth’s suggestion, Lelchuk would treat the encounter as if he were teaching a class.

Roth was an artful ally not only of Lelchuk but of Roger Straus: he knew of Straus’s anger in 1970 over the slight to Portnoy’s Complaint when it failed to win the National Book Award.

Mailer attacked the moment Lelchuk and Roth were seated: “I’d like to beat you two guys to death,” he shouted. “Understand me?” Roth angrily responded, according to Lelchuk’s account, with “Don’t you pull that stuff! You’re not going to bully me or Alan with that violent talk! Got that?” Garbus tried to establish some order. (Pete Hamill, the journalist, was to be Mailer’s second, but he didn’t show.)

Mailer then went after Roth as if he, not Lelchuk, had written the scene. It turned out later that Mailer had not read Roth’s Esquire piece, nor the book in galleys. Rembar, Mailer’s cousin, they later learned, then tried a different tack: just remove the scene. Garbus cried censorship, supported by Roth. Mailer backed down, but for the next two hours there was a mixture of “Hemingwayesque profundities and Hollywood poses, and all the way through a stream of physical threats.” Mailer was convinced that either Roth or Philip Rahv put Lelchuk up to writing the offensive scene, encouraging would-be assassins and holding him up to ridicule. Lelchuk responded by claiming that Mailer always provoked people to an adversarial, combative, and even murderous stance toward himself and referred to him as the “Muhammad Ali of novelists.”

But Mailer could not separate criticism from ridicule, offering new antagonisms toward Styron, Bellow, and, of course, Roth, who had suggested using Mailer’s own words against him. Mailer responded by stating that the depiction of his death was more fitting for Roth than for Mailer. Taking his pants down in order to survive was the way Mailer would depict Roth behaving if Mailer were writing the scene. “Obviously,” Lelchuk wrote, “I didn’t know the first thing about Mailer himself.” Lelchuk again argued that it was his protagonist, Lenny Pincus, who acted with dishonor in the scene, not Mailer. Twice Mailer said he wasn’t interested in pursuing any legal action. In fact, Lelchuk felt he met not Mailer the defender of freedom but a fake, an imposter: “Beneath the studied rage, the venal bullying . . . was an ordinary man whose feelings were hurt.” The meeting ended as it had started, with threats, Mailer in a Godfather-like tone whispering, “Revenge is a dish tasted best when cold.”

__________________________________

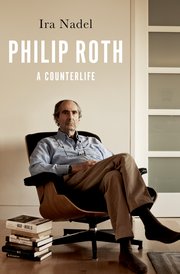

From Philip Roth: A Counterlife by Ira Nadel. Copyright © 2021 by Ira Nadel and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Ira Nadel

Ira Nadel is Professor of English at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver and is the author of biographies of Leonard Cohen, Tom Stoppard, David Mamet and Leon Uris. He has also published Biography: Fiction Fact & Form, Joyce and the Jews and Modernism's Second Act, in addition to a Critical Companion to Philip Roth.