1. An Auditorium in Grand Rapids, Michigan, April of 2012

Marilynne is delivering the plenary address at the Festival of Faith and Writing. Some years ago, in one of her seminars, she told us that she rarely knows where a sentence will take her when she launches into it and that every claim she makes should therefore be understood as approximate, tentative, but it has always seemed to me that even when she’s improvising she speaks in perfectly formed essays. Here, listening to her talk about guns and fear and the myth, as she calls it, of Christian embattlement, I find it hard to tell when she crosses the gap that separates her prepared remarks from her extemporizations, or if there even is one. You will never find the suggestion in the Bible that there is not a human being made in the image of God, she says. So who do you want to shoot? she asks. Which image of God has been getting on your nerves? I am sitting toward the back of the auditorium, which is filled to capacity. I remember an anecdote about Harold Brodkey—how once, running on the track above the basketball court at the West Side Y, he heard cheers and shouts erupting for the winning team and broke down in tears when he realized that as a writer he would never receive such applause. At this venue, to this audience, Marilynne is a basketball team.

2. My Bedroom, Little Rock, Arkansas, July of 1995

It is the last Saturday in July, a few weeks before I am scheduled to load up the U-Haul and move to Iowa City, and I am spending the afternoon reading. Earlier this month I found a copy of Housekeeping at a nearby bookstore, along with titles by Frank Conroy, James Alan McPherson, and Thom Jones—the rest of the faculty. Before I was accepted into the Workshop, I had never heard of Marilynne or Housekeeping, nor, for that matter, of Stop-Time or Elbow Room or The Pugilist at Rest, but for three or four hours, as I lie on my bedroom floor absorbing the novel from cover to cover, I hardly move, while beneath my skin I seem to possess another self, thinner and freer, made of electricity and air, which sways as I turn the pages.

I don’t feel like I’m dancing even when I’m dancing, so it takes a lot to make me feel like I’m dancing when I’m reading. At 22, I have developed the almost ritualistic habit of equating my favorite novels with my favorite albums. Housekeeping, I decide, is Iris DeMent’s My Life, a lament for the elementally alone, soaked in a quiet sadness, but affecting above all else for the way it transforms its pain into melody. There is no photograph of Marilynne on my copy of the book, only a brief biographical note. When, I wonder, like everyone else who reads it, will she write another?

3. A Workshop in Iowa City, September of 1995

Because of my love for Housekeeping, I have enrolled in Marilynne’s workshop. The story I have handed in, though, is less Iris DeMent’s My Life and more They Might Be Giants’ Lincoln: an experimental fairy tale about the imp-like child-thief Rumpelstiltskin—or rather one imp-like half of him, the left, who has emigrated to America and is enduring the tedium and estrangement of his condition. Its sentences aspire to spring and play, romping like a cub through the outlands of my vocabulary. A Mad Libs-style fill-in-the-blanks page appears midway through the proceedings. Never in the history of workshop stories has a workshop story been less like Housekeeping. Nevertheless, Marilynne gives it a gracious reading. The narrative presents its meanings, she suggests, like life does, offering them up discretely, with long separations between them, so that the only way to achieve the meaning that follows is to trust your weight to the meaning under your feet. Life is just that probationary, just that contingent, like lily pads, she says, across the abyss. She feels duty-bound, though, to point out how frequently I use the word that in the last few paragraphs, and how scantly all those thats contribute to my prose. A that racket, she calls it.

4. My Desk, Little Rock, Arkansas, January of 2020

I am trying to write an essay about Marilynne Robinson: one small contribution to a collection of—this is the word with which the editors have approached me—encomia. Last month I finished one of my occasional visiting appointments at the Writers’ Workshop, my sixth since 2005, where Marilynne was once my teacher and has secretly, apparitionally, though no one but me is aware of it, remained my teacher ever since, even during those semesters when I’ve more or less successfully disguised myself alongside her as faculty. The problem is that I’ve barely approached the keyboard since returning home. Everything about writing that once came by instinct to me comes as an exertion right now. Can you teach yourself into a creative fog? I am wondering. I hope that if I forget about cogency, forget about art, and simply hand myself over to my recollections, they will reveal a structure to me.

First semester, second. Workshop, seminar, seminar, seminar, thesis. Suddenly I remember a thoughtless statement Marilynne once overheard me make, something about unreliable narrators and classical mythology, and I groan, literally, out loud, with embarrassment. Perhaps, I think, I should center the essay around this exact feeling—all the embarrassments to which Marilynne has seen me subject myself over the years. A structure! I could mark each embarrassment with an asterisk. This seems too narcissistic to me, though, and I dismiss the idea.

5. Thisbe Nissen’s Backyard, Iowa City, May of 2000

I keep having dreams that I am back in Iowa City. They are always the same, these dreams, pre-dawn anxiety spirals in which I discover, while making the bookstore rounds, that Murphy-Brookfield, Haunted Bookshop, Prairie Lights, The Bookery, have all been transformed into bewildering right-angle mazes, the shelves of Dalkey Archives and Vintage Internationals replaced with candles, tchotchkes, and greeting cards. In my dreams, without exception, I am on my way to Thisbe’s. I repeat these words to myself: I am on my way to Thisbe’s. But this weekend is the first actual return trip I’ve taken since I graduated. Thisbe is hosting a cookout behind her house, and to my surprise, Marilynne has shown up. I am standing on the back porch steps, she nearby on the grass.

Away from the classroom, I have never quite known how to strike up a conversation with her. In my discomposure, I am always afraid that I will blurt out some half-baked opinion about, say, the Apostles. But instead we begin discussing the internet. We constitute, it turns out, a minority of two. Neither of us has acquired an email address. Neither of us can see the virtue of it. I don’t even have the inclination to answer my regular mail, Marilynne says, much less, you know, all this, and I agree. We confess, though, that we have each borrowed other people’s computers to buy books, books we doubt we would have found otherwise. We agree on this, too: that the internet, if nothing else, has made it easier to fill the gaps in our libraries.

6. The Frank Conroy Reading Room, Iowa City, February of 2017

Eight months: that’s how long Marilynne’s been retired; and Shakespeare and his presentation of consciousness: that’s the subject of her emeritus lecture. We make a mistake, she argues, when we regard Shakespeare as some abstract forebear whose achievements are beyond genuine human reach. He does not exist at the margins of our own imaginative capacity, she insists, he exists at the center, and the greatness of his accomplishments suggests, or should, not that we are smaller than we suppose ourselves to be but that art is bigger. I am in a chair with a cracked wooden shoulder facing a set of windows overlooking the white sky and the gray trees. Isn’t it funny, I think, how something sprightly happening in the brain can make you feel at ease inside your body? I kind of—and I’m embarrassed to think it, and she would be embarrassed to hear it, but it’s true—venerate Marilynne. The questions she draws after she has finished speaking range far afield from Shakespeare, but she answers them gamely. She is as skeptical, it turns out, about Bob Dylan’s recent Nobel Prize win—Well, it’s their prize, the Swedes. They can award it to whomever they choose—as she is about the Presidential election—I’m just not sure a reversion to feudalism is the answer to the problems that are facing our country. As the room is emptying, I approach her to say hello. She clasps my arm. I’m still using my Kevin Brockmeier dictionary, she tells me.

7. A Seminar Room in Iowa City, February of 1996

This week, in Marilynne’s short story seminar, we are discussing “The Minister’s Black Veil.” Hawthorne, I have noticed, uses two different spellings when describing the veil’s fabric: crepe and crape. I take these variations, the e and the a, to be meaningless, but then I wonder—is there a difference? Sometimes, consulting the dictionary on a quick mission of curiosity, I will hand myself over to impulse, and 30 or 40 minutes will go by before I emerge hundreds of pages from where I started, like some storybook itinerant unwise enough to take a shortcut through the woods. It is a manual of sorcery, the dictionary, not just a glossary but a vocabularium. And here, at Iowa, I have begun to think of it as our greatest act of shared cultural creation, a record of all the experiences we have ever valued enough to name. Dap: for the skipping motion a stone makes on the water. Callithumpian: for someone or something that belongs to a band of noisy or discordant instruments. That such words exist at all—merely exist—is beautiful to me.

Yesterday, while I was rereading Hawthorne’s story, I discovered during one of my explorations that crape-with-an-a, the more archaic of his two spellings, was a late-17th-century noun that referred specifically to clerical dress—and, by transference, to a clergyman himself. Where could you possibly have learned that? Marilynne asks, and I tell her, The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Well, she says, I think you’ve come up with an entirely new interpretation of this story. Imagine what the Unabridged would reveal.

8. A Workshop in Iowa City, Late November of 1995

The question is whether or not we’re dealing with an unreliable narrator here, and, says Marilynne, turning to look me hard in the eyes, that is important. I worry that I have committed an irreparable wrong and she dislikes me.

9. The Sidewalk Outside Prairie Lights, Iowa City, April of 2009

It is spring in Iowa City, a sort of two-week pipe through which the snow spills into the river each year. The trees are donning their clothing, the undergraduates casting theirs off, and the air smells mysteriously like maple syrup. Several of my students are availing themselves of the warm weather to linger on the sidewalk after an evening reading. I overhear them discussing the Workshop prom, only a Saturday or two away. Are you going? they want to know, but of course I’m not. It’s an unofficial event, albeit longstanding, and to my knowledge no one from the faculty ever attends. I mention that back when I was a student I had a fantasy of asking Marilynne to be my prom date, with a tuxedo and a corsage and everything, but lacked the courage to follow through with an invitation. Did you have a crush on Marilynne? someone asks. I possess the bad habit of treating questions like this seriously, rather than as an opportunity for repartee. All it does is make people uncomfortable. An aesthetic crush, I say.

10. A Workshop in Iowa City, October of 1995

One of my classmates has written a story that mentions a vintage gas street lamp, first illuminated in the 1820s, the globe of which, the narrator observes, still holds the breath of the original glass-blower. When Marilynne points out that such lamps aren’t airtight, and that the attribute he has assigned to this one is therefore impossible, the workshop greets her with a group-noise of disappointment. Look, I agree, she says. It’s a lovely idea. But alas. Sometimes she makes an aquatic motion with her head when she wishes to convey the impression of a laugh without actually laughing. Maybe you can imbue some other vessel with the breath of the departed? she proposes.

11. The Old Capitol Mall, Iowa City, May of 1997

Alex Parsons and I have seen an afternoon movie. We are leaving via the escalator’s downgoing staircase. We reach the landing plate just as Marilynne is approaching from the concourse. The three of us pause there, exchanging hellos, while the automatic steps make their continuous mall sound, like a deck of cards that never stops shuffling. Alex and I have recently graduated from the workshop, and because he will be moving away soon, he says to Marilynne, he should take this opportunity to thank her for her generosity. He’s found her classes enriching. He wants her to know he’s appreciative. By the common laws of conversation, it’s my turn now, but all I say is, I’m not leaving yet. I’ll see you again. Later that day, it will occur to me that it must have sounded as if I was saying I did not find your classes enriching, I am not appreciative, I must take this opportunity to thank you for nothing, and I will feel as if I am on the escalator again, sinking between floors. Asterisk.

12. A Stairwell in the English-Philosophy Building, Iowa City, January of 1996

I write a story about palindromes. The sections proceed palindromically, from one to nine and back to one again, and the story adopts a palindrome for its title: “Did.” In the stairwell one day, Marilynne asks if I received the letter she wrote me about the story. Yes, I say. Thank you. You kept calling palindromes palimpsests, though. Anyone who admires Marilynne’s books can probably surmise how intellectually adroit she is in conversation, how decorous, how eloquent and how exacting, but unless you have actually spent time in her company you might fail to perceive what I regard as the true predominating quality of her character: her amusement. Whatever the opposite of a barbed laugh is—a hospitable laugh?—that’s what she gives. Pausing in the stairwell, she says, What a delightful misstep. And then: There’s a similarity of effect there, though, right? Two phenomena that are only able to come into being over their own earlier traces.

13. A Reading at the Main Library, Iowa City, on a Particularly Cold Night in December of 1996

Of course I walked here, Marilynne answers us. She shakes the snow from her coat. I mean, who am I? I start driving a car and the next thing you know I’ll be carrying a gun.

14. A Seminar Room in Iowa City, Early November of 1995

For now the classroom is mostly empty. Everyone else is taking advantage of the mid-seminar break, smoking or peeing or refilling their coffees, but Kim Knutsen and I have remained at the conference table, listening to the thermostat tick and the heat sigh out of the vents. We begin trading notes about our workshop instructors. So what about you? she asks. Who are you taking? and I answer, Marilynne. Really? Kim says. For Faulkner and workshop both? What’s that like? I tell her how subtle the workshop is, how passionate, how funny, tell her about Marilynne’s friendliness toward Emily Dickinson, her skepticism toward Jane Austen, and about the lily pads, and about the beetle incident. So no complaints? she asks. Nothing at all? I give the question some thought. The chairs are filling back up, the air vibrating with additional conversations, when I say, Sooner or later, one way or another, everything turns out to be about unreliable narrators and classical mythology. That maybe is something I don’t get. By now, the whole class has returned to the table, including Marilynne. By the needlessness with which she rearranges her papers, by the concentration with which she averts her face, I understand that she has overheard me. A sky full of asterisks. Enough asterisks to make a Milky Way.

15. A Theater Lobby in Grand Rapids, Michigan, April of 2012

I have been invited to the Festival of Faith and Writing, I am told, by virtue of my writing, not my faith. My credentials are solid enough. No need to worry. One out of two is plenty. Still, as an agnostic, it is hard not to think of myself as a kind of mimic-bird in this place. Do I really belong here? Whose spot have I taken? Faith, in my books, is a substrate for fantasy, God and the afterlife arenas for storytelling. It is not so much that I am faithless as that my faith is delimited by—and a product of—writing itself. I tell myself that that is enough. If ever a venue and a speaker were perfectly matched, though, it is here and it is Marilynne. After her plenary speech, she is escorted to the book-signing table. Of the thousand-some audience members, fully half join the line. These aren’t author-numbers in my experience; they are actual-famous-person-numbers; and this, at least, is a faith I can share: a reader’s faith in a particular writer. Above all else in this particular writer. When I reach the table, Marilynne introduces me to her chaperon. Here, she says, is one of our success stories, and taking the shuttle back to the hotel, I play a segmentation game with the phrase. Which suggestion, I ask myself, do I find the most complimentary, the most salutary: that I am (a) a success, (b) a story, or (c) one of hers?

16. A Workshop in Iowa City, September of 1995

A beetle is trooping across the conference table. It is roughly the size and shape of a watermelon seed, and at each lull in the conversation, before someone has the opportunity to break the silence, we can hear its carapace going tak-tak-tak against the tabletop. For some reason, it keeps approaching Marilynne, looping toward her manuscripts and glass of water and then back to the center of the table as if on a rail. Each time she brushes it away, the gesture she makes says one thing only, but says it so clearly, Shoo little bug, that she might as well be saying it out loud. On your way. Go about your business. We have no argument, you and I. To me, this is the real drama in the room, not the story we are discussing but the beetle making its strange little overtures and Marilynne politely deflecting them. Call it a stalemate, call it a dance, it could go on this way forever, I think, but then the bug marches up to Peter Meyers, who in a moment of inattentiveness, and with barely a pause, makes a fist and mallet-flattens it. The room hits an air pocket, and he says, Sorry about that.

17. The Macbride Hall Auditorium, Iowa City, October of 2019

Connie Brothers is retiring after 45 years as the Workshop’s administrator. Marilynne begins her tribute by saying, I come to you from weeks if not months of self-imposed but nevertheless penal seclusion. She has, she apologizes, been trying to end a novel, a novel that will not end, which is why her remarks will be brief, she says, but deadly serious, and with those words—deadly serious—she alights as she so often does on a tone that is one-quarter comic, three-quarters earnest. After the banquet, as everyone filters toward the elevators, she spots me in the hallway. So the book, I ask, part of the Gilead trilogy? Not any longer it isn’t, she answers, meaning: Quartet. The finish-line keeps retreating, she says, but I keep approaching it. With the daily help, she emphasizes, of my Kevin Brockmeier dictionary. I do not say, as I always am not saying, Housekeeping! I do not tell her, You changed the kind of writer I was going to become. I do not tell her, Never in my life did I think I would have a conversation this easy or reassured with you. I do not tell her, I kind of—and I’m embarrassed to think it, and you would be embarrassed to hear it, but it’s true—venerate you.

18. A Workshop in Iowa City, February of 2012

Before class one Monday, from my office across the hall, I overhear one of my students talking to another. He crossed out all the thats in my story, she says.

19. A Seminar Room in Iowa City, February of 1996

Last night, Marilynne tells us, I dreamed I had died. I was laid out in a coffin, in my parlor, with a pillow supporting my head, and though I still had all my senses, I knew that I was dead, not just sleeping. My family were sorting through a box of my photos, trying to decide which ones to display at the viewing, old photos, recent ones, and I realized—I could see suddenly—that the photos were filled with light. Everyone I had known and loved, or known and forgotten, even the pets, even the houseplants, had suns burning inside them. And a sun was burning inside me, too. And I thought, It’s all so beautiful. Why didn’t I understand how beautiful it was while I was still alive?

__________________________________

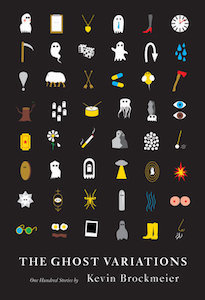

The Ghost Variations: One Hundred Stories is available from Pantheon, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Brockmeier.