When Love is Almost Too Much To Bear

Heather Harpham on the Moments That Define a Life

Everyone in the world should have the chance to fall in love in a New York City spring, at least once. Spring, in New York, is like a new epoch in history. The sludge recedes; the trees return as green civilizers of the streets. Your beloved finally takes off all those obfuscating layers, and you can see skin. The Josh Ritter song goes something like, “It’s been done a hundred thousand times before, but this one is mine.”

On a Saturday, three or four months into our courtship, I found myself staring down from Brian’s 26th-floor window, watching the Upper West Side swish below. I wanted to go to a gallery, a café, Riverside park, bike riding along the Hudson. I wanted to take the train downtown to Magnolia Bakery for a lemon-frosted cupcake. Anything, just out into the tides of the town. But Brian was at his desk, happy in his misery. Wringing something more out of the imagination by sheer attendance. Showing up. Seeking. Day by day. He had his hands on the keyboard, and his eyes closed, tunneling in, burrowing down. This was something he did occasionally, write blind. He was deep in conversation with his unconscious, his imagination, his genie. Whatever the hell it was that wrote his books, he was chatting with it. Just the two of them, tete-a-tete.

He didn’t seem to need a lemon cupcake.

I knew we’d go out later. I watched the sun drop into the river, pressed my cheek against the cool glass and waited. The world was out there, true, but it was also in here.

When we left, to meet friends for dinner, it was still warm out. The sidewalks felt almost pliable underfoot, willing to bear us in any direction. We linked arms and headed downtown. My sweet hermetic boyfriend, out in the world. Traipsing around. I tucked one hand into his coat pocket. The payoff for this simple gesture was absurdly inflated. I wanted to see a scan of my brain, to know exactly which synapses electrified, like webbed lightning, when Brian put his hand in my coat pocket too.

*

I was not allowed to watch the procedure in which they inserted the tube into the baby, but I heard crying from down the hall. Was it my girl? Impossible to know. Even more impossible to know what she might be feeling, thinking, or understanding about the world–alone in a room of white coats.

My mom brought me a tea; I sipped it, queasy. I wanted the baby back. We should be in bed at home together. I should be in a flannel nightgown, snuggling her, emitting the primary message: you are loved.

When I could no longer stand listening to the cries of a baby who might or might not be mine, I stepped into the pay phone booth in the waiting room. I shut the door. Silence. At last, a small private space in which to feel something.

My mom tapped on the glass of the booth, holding out the tea. “Don’t let it get cold.” I opened the glass door and took the tea, annoyed. If, years from now, my own daughter was in this same situation, I would, undoubtedly, hover. Peddle tea. But it was still annoying. I considered calling Brian. I wanted his support but not enough to make the baby’s illness real by telling him about it. Instead, I dialed my health insurance company. When a representative answered, I told her my name, my group ID number and said, “My daughter is sick. We’ve been transferred to UC Med.” It was the first time I’d said my daughter.

My voice broke, and the woman paused. “It’ll be OK, dear,” she said. She could be empathizing from Ohio, Singapore, or a block away. She could be anywhere. So how the hell did she know how it would go?

When I returned to the waiting area, I picked up an old issue of the New Yorker. On the cover, beleaguered cartoon figures marched through eddies of gray sludge and snow, huddled beneath a banner that read “Misery Day Parade.” February. I held it up for my mom to see, pointing to the banner of hand-printed letters, Misery Day Parade. “Oh, sweetie,” she said. “I know.” And she did know. She was a professional understander, a therapist. The rare kind, with a heart of true compassion. Maybe because she’d suffered so much as a kid, maybe because she was born that way. She never dealt in pity, only empathy. But at the exact moment I needed it most, I didn’t want it.

Every gesture of comfort she offered only underlined the obvious: she was my mom, and, therefore, not Brian.

*

I loved, for one, his books. Not just the books he’d written, but also the books he read. They were everywhere, on every surface: the lip of the bathroom sink, the windowsill, stacked in unstable towers on the DVD player, in doorways, and endlessly, on the bed.

He’d climb into bed with his intellectual posse: Chekhov, G.K. Chesterson, George Scialabba, Irving Howe, Raymond Williams, but also Robert B. Parker and Roger Angell. In terms of heroes, he had a take-all-comers approach; he’d once written an essay on his affection for the TV show The Equalizer. Books on antiquated English grammar by patrician midcentury taskmasters, on efficiency in the work place, labor histories, lurid crime novels—all would flop over the pillows, work their way under our feet. Reading the ideas of others wasn’t just what he did, it was what forged him into who he was, word by word.

He was not a person who called himself a writer but was actually an architect or a pastry chef. Reading and writing were his air and water. He was a writer, who wrote. Every day. For hours. A novelist. A published, award-winning novelist. A self-doubting, slow-working, often frustrated novelist, but a serious artist. Writing was at the core of his existence, and everything else fell into place around that central fact.

Even when he wasn’t writing, he was writing, inventing, trying things out. Once, when I asked him to tell me the story of his name, he reported that instead of Brian his parents almost named him Barrel after a Hungarian relative, a glue maker and war hero, who died by falling, face-first and drunk, into a barrel of glue. He told me this very solemnly, and I was relieved that he had not been named Barrel. It might have changed the course of his life. Would we have met? When I asked his mother about her cousin Barrel who had tragically, ironically, drowned in a barrel, she laughed and laughed. “For such an honest guy,” she said, “Brian is the world’s biggest liar.”

He had his books, his Joe Louis postage stamp, his habits, his broccoli, his blue shirts, his cabal of imaginary friends, his never-ending mental arguments with Noam Chomsky. He had his uninterrupted days and nights at the keyboard. He had solitary writer written all over him. And, as much as he enjoyed being with me, he obviously didn’t want kids or a family. Writing was the sun around which the rest of his life orbited, including me. So, how long could this last?

If we went on, if he allowed me into the inner courtyard, then what? I was afraid I’d have the perverse urge to blow things up, disturb and disrupt, the way you want to toss your hat from the top level of the Guggenheim into the tiny reflecting pool below.

*

The first few weeks of my pregnancy, oblivious to my condition, I dashed into every Starbucks I saw. I couldn’t understand this sudden compulsion—I’d never been a coffee person. Not even close. In fact, I’d once presented myself to NYU medical center with heart palpitations after eating a bag of chocolate-covered espresso beans. The doctor asked, “Have you had a lot of coffee today?” I was indignant: “I don’t drink coffee.” Then I remembered, but didn’t confess. Just slunk away in shame, the only woman in New York City who couldn’t hold her caffeine.

I ordered lattes, macchiatos, cappuccinos, any foamed formula with espresso. I was puzzled, but compliant, caffeine’s willing handmaiden. The more sophisticated drinks lent me, I hoped, a certain chic. I loved their Italian names, the long vowels. Holding a perfectly frothed macchiato was tantamount, in my book, to wearing a blue cashmere wrap. And then I began to wonder; a little seed of doubt presented itself. Why was I craving coffee? Why was I craving milk? Why was I craving?

I happened to be in California, visiting my family. Our local drug store was a ten-minute tromp through a wooded park, a trek I’d taken a thousand times for candy, makeup or magazines. I went straight to the feminine hygiene aisle, a place I was once loath to be seen loitering, and bought four pregnancy kits of various brands, all promising speed and accuracy.

You are supposed to pee on the stick at a certain time of day, under particular conditions. (Reading the directions I kept hearing the slogan from a radio show I’d liked as a kid, “It’s Science!”). But I couldn’t wait for science. I just pulled out a stick and tried not to pee on my hand. I put the plastic cap back on and waited. One minute, two. A faint line began to appear, just the dimmest purple dash across one display window, and then another line, crossing the first, forming a lavender plus sign. Plus one. Oh God. Oh God’s God.

I ripped open another package and forced myself to pee on that. And another and then the last. They all had dashes and checks or hazy blue lines. I couldn’t believe these little sticks. They were unanimous, unwilling to negotiate.

I found my running shoes, laced them up. I’d walk up the hill. By the time I got back, maybe the pregnancy would have run its course.

Next to my shoes was one of Brian’s, a black Converse sneaker. He’d just spent two weeks with me in California, meeting my family, laughing with my college friends. We’d driven up the coast together, along Highway 1, traveling from LA to Marin County, passing through Big Sur, the most beautiful place on the planet, where we’d pulled the car off the road onto a secluded apron of land above the ocean, just to kiss. We’d spent the whole two weeks in a bubble of our own invention.

I’d taken that fact that he left a sneaker behind as a good omen, his tangible wish to still be here. I picked it up on my way out. I puffed up the hill towards the fire trails, assimilating the news, clutching his sneaker. At the top of the hill was a long narrow ridge lined by giant eucalyptus trees, with an animate presence. Two sentinel rows of stolid, immovable elders who had offered me sanctuary since I was ten. The trees had delicate scythe-shaped leaves and trunks with silvery outer layers that peeled away from a pink undercoat. As a kid, I liked to rub my check against the silky inner bark, or crush the leaves in my palm. The smell cleared my head; straightened my gait. Not now.

What on God’s green earth was I going to do? Or we. Since it takes two people to set a baby in motion, it seemed fair that those same two should have a say in whether or not the baby comes to fruition. But I didn’t have that capacity for democracy. I’d told Brian all along: if I get pregnant, I will have the baby. I was willing to stand in the rain with a dripping placard to fight for the right of women to choose (though I’d never done anything remotely so noble), but I didn’t experience it as a choice. I wanted to be a mother and he was a man I loved. He might opt out, fairly or unfairly, I might hate him for that, fairly or unfairly, but the baby was a foregone conclusion.

As I walked home, the hills soaked up the dusk, turning blue-black. Then, slowly, they lit up, house by house, like a night sky. Each pinprick of light was a family. Was I technically now a family too? I housed a cluster of cells, dividing at a breakneck pace. I was, at the very least, a party of two.

__________________________________

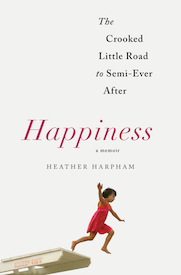

From Happiness: A Memoir, by Heather Harpham, courtesy Henry Holt and Co. Copyright 2017 by Heather Harpham.

Heather Harpham

Heather Harpham is the recipient of the Brenda Ueland Prose Prize, a Marin Arts Council Independent Artist Grant and a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund. She teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and SUNY Purchase and lives along the Hudson River with her family.