When Lawrence Ferlinghetti Defended a Tribute to Allen Ginsberg

Annice Jacoby on Hosting a “Poets Kaddish”

In spring of 1997, Nancy Peters, the remarkable publisher at City Lights Books, called with the sad news that Allen Ginsberg had died. It was hard to imagine the world without him. Allen and I were allied as poets and pacifists over decades of reasons to rally. The world knew Allen as a rapturous poet who vigorously opposed militarism, materialism, and sexual repression. My freshman year, a college senior, the emerging poet Anne Waldman, took me to a New Year’s Eve party in downtown Manhattan. At midnight, Allen led an ecstatic circle of rolling oms. This was before his notorious chant at the Chicago 7 trial. Allen’s loss felt personal, as it did for a generation of poets.

Days after Allen’s death I met with Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Nancy Peters at City Lights. They asked me to put together a performance honoring Allen for a memorial. I invited hundreds of poets to partake in a chorale the following Sunday at Temple Emanu-el. We spread the word to gather at the temple, a landmark congregation founded during the Gold Rush.

When the San Francisco Chronicle showcased the roster of luminaries joining the Poets Kaddish, Michael Savage, right-wing radio attack dog, seized the chance to condemn the event. Savage treated Allen Ginsberg’s memorial as a target for suicide bombers, claiming no temple should soil itself with “pinko f*****s.” Radio ballistics were material for Savage’s daily devouring in the days when he was still a local shock jock.

Like many under attack, I went into a zone of surprise and shameful fear. I felt responsible, to both City Lights and Temple Emmanu-el, for the fact that my passionate offering had drawn such cynical and dangerous attention. My night was completely sleepless remembering the last time I spent any real time with Allen. After a long rainy day meeting up at a bar in North Beach, probably Tosca’s, we argued about what he should read at the ballpark before a Giants game the next day (he had joined City of Poets, the San Francisco Public Library campaign staging poetry in public life).

Allen was fierce in dismissing my suggestions for a poem with universal appeal. “I’ve read to a stadium with 40,000 people in Prague. No one wanted to tame me. I don’t want to be polite to national television. I ain’t going to be no Maya Angelou for you.” That night in North Beach trying to pick a poem for the ballgame with a forcefield, I was on alert, always in a hot zone with Allen, ruffling the reactionaries.

The next day Allen knocked the ball out of the park reading his poem “Fuck bomb” to boos and cheers. My children were beaming in the skybox at Candlestick Park with San Francisco Mayor Frank Jordan, and a fleet of media. On the Jumbotron epic scale, Ginsberg bellowed, resembling an Old Testament depiction of God. Allen was such a big hit that he was interviewed on national sports radio for weeks following the Giants game. He was treated like a hero, inspiring citizens how to be powerful without being violent. He was correct: Provocateurs get more results than pacifiers.

The poets led the mourners into the chapel, everyone chanting under the celestial turquoise dome of stars.

Now three years later, Ginsberg had died and Michael Savage took the Chronicle article as bait to go on the attack. The memorial was Savage’s red meat. He harped and carped on insidious familiar fears that gained traction, even in the progressive Bay Area. Racist and homophobes reside all over. Even after the fall of the USSR, the Peace Dividend had not abated commie baiting.

I complained to Lawrence, “Isn’t it crazy how this shlock jock is living up to his name, yes that is his real name. Like Donald Trump destroying Atlantic City: bad jokes about Trump cards play to empty casinos. All cashed out. Savage is a beast, takes pleasure in attack.”

Without hesitation, Lawrence put things in perspective. “This Savage attack would not have ruffled or reduced Allen! Man up to the haters. Bow down and you give them license. I am more worried about the temple as a target of anti-Semitism. We are organizing a mass public poetry kaddish.”

The next morning Nancy, Lawrence, and I had an emergency meeting with Temple Emmanu-el’s chief rabbi. In the past 24 hours, there had been a barrage of bomb threats and congregant complaints. Ferlinghetti insisted, lamenting the loss of his beloved friend, “Allen Ginsberg must be honored in the city he first read “Howl.” Allen’s words still throb: Trust what you see. Yes, the insanity in the supermarket aisles. Yes, the airwaves full of madmen.”

The rabbi was also adamant. “The memorial must go on. Capitulating to nasty intimidation would be contrary to everything Allen believed in, lived for and manifested.” We were emboldened to proceed. I was relieved but still nervous. Security would be beefed up.

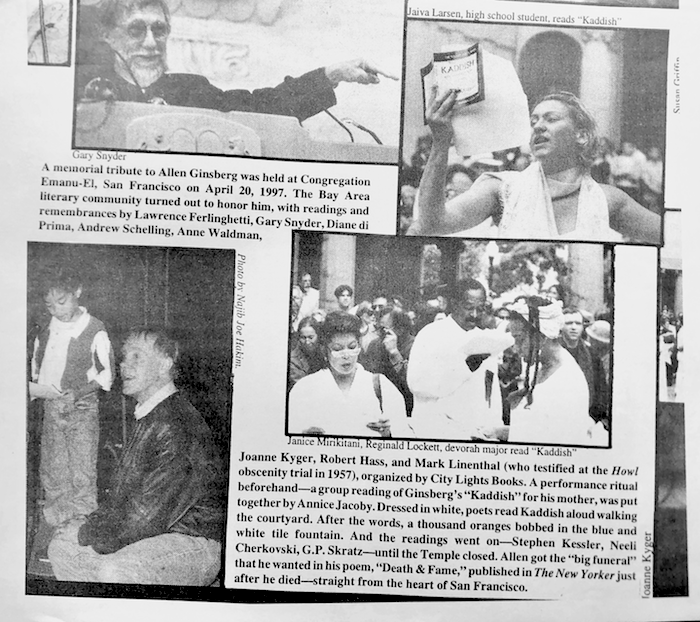

On Sunday, thousands of mourners gathered, with many more thousands turned away for lack of space. Poets performed a grand oratorio drawn from Ginsberg’s elegiac “Kaddish,” a poem he wrote after his mother’s death riffing on the traditional Jewish mourner’s prayer. The temple courtyard was lavishly scented by thousands of oranges floating in the Moorish fountain. The poets, all dressed in white, the color of mourning or purity and hope, sang a lament of Ginsberg’s words, incantatory repetitions, dancing through the crowd they formed a processional of people praying and crying through the arched columns. The poets led the mourners into the chapel, everyone chanting under the celestial turquoise dome of stars.

Time now for Ferlinghetti, for his poets kaddish, or aria of lament. The beat will go on. The mourners’ words will roll in healthy dissent, purposeful euphoric living and shake all assumptions. Lawrence Ferlinghetti is an everlasting star in our literary cosmos.

Annice Jacoby

Annice Jacoby is a writer and artist in San Francisco. Her work includes Street Art San Francisco: Mission Muralismo (Abrams), Fort Point Project, opening performance of the Hague Appeal for Peace, City of Poets with San Francisco Public Library, and UNDERCOVER, to rally solutions for the homeless humanitarian crisis. www.annicejacoby.com