When in Doubt, Smile Like

an Axolotl

Aimee Nezhukumatathil in Praise of the Mexican Walking Fish

If a white girl tries to tell you what your brown skin can and cannot wear for makeup, just remember the smile of an axolotl. The best thing to do in that moment is to just smile and smile, even if your smile is thin. The tighter your smile, the tougher you become.

Give them a salamander smile. The axolotl (pronounced ax-oh-LOT-ull) is also known as the “Mexican Walking Fish,” but it isn’t actually a fish—it’s an amphibian. Axolotls are one of the only amphibians that spend their whole life underwater and neotenous, or without going through metamorphosis. Axolotls vary in color, depending on which of their three known chromatophores they inherit—iridiphores (which make axolotl skin shimmer with iridescence), melanophores (shading them a swampy brown), and xanthophores, which turn them a pretty rose gold shade of pink.

Most that are called “wild-type” axolotls have a bright ring around their unblinking eyes like someone took a neon highlighter pen and used it as axolotl eyeliner. Wild-type axolotls have been known to sometimes pop out of their eggs first as the loveliest, ghostly shade of gold with pink eyes, only darkening their skin and eyes as they grow older to blend into their murky surroundings. But for my money, the most striking axolotls are leceustic—pale pink with black eyes. This is the type of axolotl most commonly kept as class pets in hundreds of elementary school classrooms, and it’s usually leucistic axolotls—with the pale pink color and that unforgettable upward curve of its formidable mouth that you see—on stickers and t-shirts, and even snuggly stuffed animals.

You remember trying out various shades of Wet n Wild lipstick, including a red the color of candy apples, in the junior high locker room after gym class. Your mother never let you wear lipstick, and boys had not yet begun to notice you. You only wanted to experiment, to hold a tube of color up to your cheek the way you would hold a sequined dress to your body in front of a mirror. Still, you loved the way the lipsticks clacked in your friends’ purses like dice, so you decide to try the boldest shade of red. I don’t think someone with your skin tone . . . should wear red. You might want to try this instead, said the girl who didn’t have any brown friends besides you. The only brown folks she knew were on The Cosby Show. You adored her, though, and you were the new girl yet again. You didn’t want her to stop waiting for you at lunchtime, so you smiled, shrugged, and mumbled, You’re probably right.

But even from that brief application, you fell in love with and slightly feared that slash of red, a cardinal out of the corner of your eye, lending definition to the outline of your mouth. A mouth that was used to speaking only when called upon. A mouth that stayed shut when you knew the answer because you didn’t want anyone to roll their eyes or mutter Teacher’s pet! like they had in years prior. Instead, you wiped off the red lipstick with wadded-up toilet paper and forced a smile, leaving the locker room with a pale, cotton candy-colored lipstick that made you look wan and parched instead.

An axolotl can help you smile as an adult even if someone on your tenure committee puts his palms together as if in prayer every time he sees you off-campus, and does a quick, short bow, and calls out, Namaste! even though you’ve told him several times already that you actually attend a Methodist church. But it’s as if he doesn’t hear you or he does and doesn’t care, chuckling to himself as he shuffles across the icy parking lot, hands jammed into his pockets. Wide and thin, the axolotl’s smile runs from one end of the amphibian’s face to the other, curving at each end ever so gently upward.

Perhaps second in distinctiveness only to the axolotl’s smile are the external gills on stalks that fan across the back of its head, three on each side, like an extravagant crown of fuchsia feathers radiating from its neck. The average axolotl grows to be just over a foot long and dines on all manner of worms: blood, earth, wax. It also fancies insect larvae, crustaceans, and even small fish if it can find some.

Scientists have taken to studying axolotls for the regenerative properties of their limbs—very unique in the animal world, because axolotls don’t seem to ever develop scar tissue to hide damage from a wound. Axolotls can even rebuild a broken jaw. In recent experiments, scientists have crushed their spinal cords and even that regenerates. Scientific American reports that you can cut the axolotl’s limb off at any point—wrist, elbow, upper arm—and it will make another. One can cut off various parts of arms and legs a hundred times, and every time: the smile and a bloom of arm spring forth like a new perennial. Just when one thinks nothing can grow back after such a winter, the tiny, pale shoots of a crocus burst through the sloppy mulch-thin ground after a difficult and heavy sugar snow. An impossible wound begs to differ with its body and says, I’ve got another. And another. These tests involve the repeated amputation of limbs over a hundred times. What does the lab technician say after the 95th day, perhaps, of this kind of work? Just five more to go, and we’ll close up the report! How does that person come home and forget those hundreds of estranged arms and legs? It’s hard to remember axolotls are endangered when you see their bodies regenerate parts so quickly, when they “smile” at you in aquariums, their pink gills waving as they study you and your own fixed mouth.

Particularly devastating about these amphibians is the fact that the people who created the International Union for Conservation of Nature have determined there are no more axolotls in the wild. None! Wild axolotls used to swim in abundance in two particular lakes in Mexico, but there haven’t been any documented cases of finding wild axolotls since 2013. One of the lakes was drained as a result of the growth of human population—growth in Mexico City—and the other is recently overrun with carp, which gobble up axolotl eggs like M&M’s. Axolotls are now found in aquariums and fish supply stores, to be sold as pets.

In spite of the axolotl’s seemingly serene visage that often tricks people into thinking of cuteness and perhaps a gentle restraint, axolotls are pretty enthusiastic—sometimes even cannibalistic—in their eating habits. But nature has a way of giving us a heads-up to stand back and admire them at a distance or behind glass—an axolotl’s forelegs don’t just end with sweet millennial pink stars; they are claws designed to help the axolotl eat meat. And when it eats—what a wild mess—when it gathers a tangle of bloodworms into its mouth, you will understand how a galaxy first learns to spin in the dark, and how it begins to grow and grow.

__________________________________

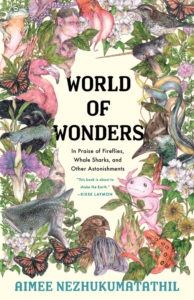

This excerpt from World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments (Milkweed Editions, Aug. 2020) first appeared in a different form as the 2017 Meridel Le Sueur Essay in Water~Stone Review.