When England Tried to Tame Ireland’s Unruliest Province

Anna Whitelock on the Creation of the Ulster Plantation and Great Britain’s Early History of Colonialism

“I had rather labour with my hands in the plantation of Ulster, than dance or play in that of Virginia.”

–Sir Arthur Chichester to King James, 1610

*Article continues after advertisement

As part of his vision of a unified “Britain,” James was determined to extend royal authority and religious conformity across the island of Ireland. The Virginia colony provided some inspiration; as Lord Deputy Sir Arthur Chichester wrote in 1608, Ireland should be treated similarly to “America, from which it doth not greatly differ.”

James’s reign in Ireland had begun auspiciously. Six days after Elizabeth’s death unaware of the queen’s passing, the rebel leader Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, had surrendered to the English government thereby ending the Nine Years’ War in Ireland. It had been the latest conflict between the Tudors and the Gaelic Irish since Henry VIII was declared King of Ireland in 1542. Indeed Thomas Radcliffe, Earl of Sussex, Elizabeth’s first Lord Deputy in Ireland, remarked candidly that he had often wished Ireland “to be sunk in the sea.” English withdrawal was unthinkable, both for reasons of prestige, and because of the danger that the kingdom might be used as a springboard and rallying point for an invasion of England. Yet the cost of the war had been enormous. The queen had resorted to selling Crown lands and imposing loans, and when these proved insufficient, was forced to draw increasingly large sums from the Exchequer. It brought England close to bankruptcy.

James believed the planting of the North of Ireland would create a new British society, where colonists as “New Britons” would work together as equal partners.

Tyrone’s submission shortly before James I’s accession presented a timely opportunity for the decisive assertion of English royal authority. Yet much to the outrage of many Englishmen, James pardoned Tyrone. In return for promising to “abjure all dependency on foreign potentates and to assist the abolition of all barbarous customs contrary to the laws,” he allowed Tyrone, and the other Ulster lord, Rory O’Donnell, Lord of Tyrconnell, to retain their titles and most of their lands. It was a similar approach to that which James had taken in the Scottish Highlands. At Tyrone’s behest, no Lord President of Ulster was appointed. On March 11, 1605, the Irish Council issued a proclamation affirming that all inhabitants of Ireland were free, natural and immediate subjects of King James I, and not subject to any local lord or chief. All offenses committed before the day of James’s accession, March 24, 1603, were to be pardoned on condition of taking an oath of loyalty.

However, in the wake of the Powder Plot the mood changed. In 1606 James’s Lord Deputy in Ireland, Sir Arthur Chichester, together with Attorney-General for Ireland, Sir John Davies, launched a new wave of intense persecution against Catholics, marked by the surrender of territory, beatings, deaths and imprisonment, and the execution of priests who were hanged, drawn and quartered. In September 1607, the earls of Tyrone, Tyrconnell, their families and almost a hundred of their followers fled Ulster and boarded a ship at Lough Swilly bound for Rome and exile. It marked the start of an Irish Catholic diaspora on the European continent, the effective collapse of an independent Gaelic Ulster, and prepared the way for a more radical policy intended to fully conquer Ireland. “There was never a fairer opportunity offered to any of His Highnesses predecessors,” Chichester wrote to James in 1607, “to plant and reform that rude and irreligious corner of the North than by flight of the traitorous Earls.” The lands of the earls, together with the confiscation of the property of the lesser Gaelic lords, left the Crown with the land of six of the province’s counties—Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine, Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone—and so open to “plantation,” settlement to control, anglicize and “civilise” Gaelic Ireland.

From the beginning this was envisaged as a “British” effort. Land-hungry English and Scots “planters” would cross the Irish Sea and establish new landholdings in what would be referred to as the “Ulster Plantation.” Given the geographical proximity and perceived similarities in language and culture between Scotland and Ireland, James optimistically believed that he had a better understanding of his new Irish kingdom than his Tudor predecessors.

Plantation was an approach James had tried, albeit with little success, in the Scottish Isles. He had written of experiences in Basilikon Doron: “For those that are utterly barbarous, follow forth the course that I have intended, in planting Colonies among them,” and so, “within short time may reform civilise the best inclined among them; rooting out of transporting the barbarous and stubborn sort, and planting civility rooms.”

James believed that those people who dwelled “in our main land [the mainland], that are barbarous for the most part, and yet mixed with some shew of civility,” differed from those “that dwelleth in the Isles” and that all are “utterly barbarous, without any sort or show of civility.” While the former might be adequately subjugated by the nobility, others “planting” colonies was the most effective approach, bringing the unruly to heel and securing their submission to the authority of the English Crown.

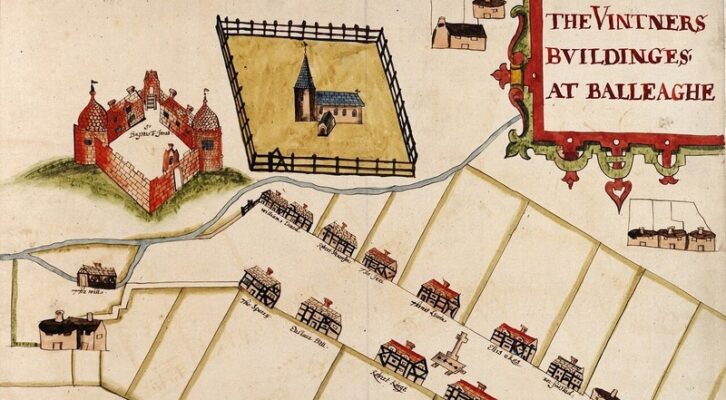

The official scheme for plantation began in 1609. That summer, surveys of each county were conducted by Lord Deputy Sir Arthur Chichester, who employed surveyors to identify the acreage of land available in each county. A plan was then submitted to the king the following year. Each county would be divided into precincts, or “baronies,” which would then be organized into estates of three sizes—1,000, 1,500 and 2,000 acres. These would be granted to three main groups of settlers (“planters” or “British tenants”) who would control, “civilize” and anglicize Ulster, which hitherto had been the region most resistant to English rule. Of the three groups of settlers, the “undertakers” were English and Scottish landowners; the “servitors” were mostly career soldiers who had fought in Ireland during the Nine Years’ War (including Sir Arthur Chichester); and the Irish “grantees” (also known as the “deserving Irish”) were those who had remained loyal to the Crown during the Nine Years’ War.

Each grant came with strict conditions. Each undertaker would “undertake” to erect a stronghold—a stone house, castle or “bawn” (fortified courtyard)—on his estate, remove the existing tenants and import settlers at the rate of 24 men per 1,000 acres. These were men over the age of eighteen and to be either English or inland Protestant Scots—in other words not the “barbarous sort” who in the isles. Undertakers could keep arms and were not allowed to lease their land to Irish tenants. All were expected to possession of their grant by September 1610 and to have fulfilled all the conditions of their grant within five years, when it was anticipated that the new arrivals would be established enough to begin paying rent to the Crown. Conditions for the servitors were similar, although they were allowed Irish tenants on their land, and had only two years rent-free. The “deserving Irish,” meanwhile, would have rent due after the first year higher rate. Some alterations were made to these conditions in the years to follow, most notably, time periods were extended, undertakers were allowed to have Irish tenants on their estates.

The establishment of twenty-five new towns—intended to be a focus of government authority, trade and industry and the Protestant religion—was to be a key objective of the plantation. Generous land grants were also given to the Church of Ireland, Trinity College Dublin, and for the creation of six new royal schools at Raphoe, Cavan, Armagh, Dungannon, Newry and Enniskillen.

Attorney-General Davies optimistically predicted that the settlement of Ulster would be “a mixed plantation of British and Irish, that they might grow up together in one nation” and “with the blessing of God.” The plantation “will secure the peace of Ireland, assure it to the Crown of England forever and finally make it a civil, and rich, a mighty and a flourishing kingdom.” James believed the planting of the North of Ireland would create a new British society, where colonists as “New Britons” would work together as equal partners, their ethnic differences melded and subsumed into one nation.

*

The cost of developing the Ulster Plantation meant that additional investment would be needed. The Crown turned to the wealthy City of London to supply some much-needed capital and expertise. In January 1610, articles of agreement were signed under which the twelve principal London livery companies agreed to undertake plantation in the new County of Derry (formally County Coleraine and parts of County Tyrone). A new body called the “Society of the Governor and Assistants, London, of the New Plantation in Ulster” (generally known as the Honourable Irish Society) was created to oversee the plantation. Each companies received an estate in the county, and these were allocated by lottery in December 1613. The companies to receive grants were: the Drapers, the Vintners, the Salters, the Ironmongers, the Clothworkers, the Merchant Tailors, the Haberdashers, the Fishmongers, the Grocers, the Goldsmiths, the Skinners and the Mercers.

In their London’s merchant companies, the government drew attention to the natural advantages of Ulster: beef, pork, fish, and game in abundance; timber for shipping; butter, cheese; hides and tallow; ports ready for mercantile traffic with England, Scotland, Spain and Newfoundland. For an initial payment of 120,000 (around 14.7 million today), the Honourable Irish Society was granted over half a million acres and other inducements, including all customs income from the plantation for ninety-nine years, and the rights to fish in the rivers and off the coasts in perpetuity.

Yet the City companies were extremely reticent about becoming involved, though they could not realistically oppose the Crown. Having reluctantly agreed to spearhead a plantation in the newly established County of Londonderry, the companies were required to follow an extremely restrictive set of guidelines that included removing all Irish tenants, building twenty-five new towns, expanding the urban ports of Coleraine and Derry (the latter renamed Londonderry) and establishing new settlements.

For the native Irish, the policy of plantation was devastating. “The Irish,” wrote an English settler in 1610, “are the most discontented people in Christendom.” They had lost their homes, their lands, their leaders and were being forced to live under foreign customs.

The planting of Ulster…had, according to his officials, began to realize James’ vision for a new “British” society.

A poem in 1610 by Lochlainn Ó Dálaigh describes Ireland through the eyes of the dispossessed. “Where have the Gaels gone?” they ask. “We have in their stead an arrogant, impure crowd, of foreigners’ blood.” While many young Irish escaped abroad—the men often recruited into continental Catholic armies other displaced Irish remained as outlaws, waiting for a chance regain their lands. As the authorities feared there was unrest, leading to small skirmishes in 1615. These gathered little as many Irish people still believed that their situation would improve, and that they would be looked after in the new society.

Indeed, one of the conditions of the grants to the planters—the removal existing Irish tenants—was not carried out. It became clear early that the Irish were needed on these estates. A later critic described “a world of Irish” continuing to live on the estates as tenants. Moreover, despite Protestant church ministers migrating to Ulster to convert the native Irish to the Protestant faith, and a national convocation of the church issuing new articles against Catholics, the Catholic Church in Ireland continued to grow in strength.

In June 1613, Ferdinand de Boischot, the ambassador of the Archdukes Albert and Isabella of the Spanish Netherlands, noted that James I had spoken of enforcing religious conformity in Ireland by armed force. But since he lacked money and feared provoking Catholics into taking “extreme measures,” such as seeking support from foreign princes, it seemed unlikely that he would follow through. William Trumbull, James’s ambassador in Brussels, reported that Irish exiles in the Spanish Netherlands were planning a new armed rebellion. In an effort to ease tensions, in January 1614 Sir Charles Cornwallis was sent to Dublin with instructions to “compose the controversies and alterations,” and negotiate a settlement which would allow for Catholic mass to be held in private. There was to be no wholesale attempt to enforce even nominal conformity to Protestantism in the province.

Upon his appointment as Lord Chief Justice in Ireland in June 1617, Sir Francis Bacon airily declared Ireland to be “the last…of the daughters of Europe, which hath come in and been reclaimed from desolation and desert (in many parts) to population and plantation, and from savage and barbarous custom to humanity and civility.” Though work was “not yet conducted unto perfection,” it was “in fair advance.” Sir John Davies, the Attorney-General in Ireland and now a significant plantation in his own right, went further: the English policy was notable for its benevolence. Whereas the Irish, “in former times, were left under the tyranny of their lords and Chieftains,” they are under the protection of the Crown. The “common people” despite being “rude and barbarous,” nevertheless “quickly apprehended the difference between the Tyranny and Oppression under which they lived before, and the just Government and Protection which we promised under them for the time to come.” He continued: “The common people were taught by the Justices of the Assize that they were free Subjects to the Kings of England, and not Slaves and Vassals to their pretended Lords.” The kingdom had been cleared of “Thieves, and other Capital Offenders;” and “these Civil Assemblies at Assizes and Sessions’ had ‘reclaimed the Irish from their Wildness, caused them to cut their Glibs and long Hair; to convert their Mantles into Cloaks; to conform themselves to the manner of England in all their behaviour and outward forms” and to learn the English language. Thus, Davies concluded, whereas the “neglect of the Law” had once “made the English degenerate and become Irish, now the execution of the Law, doth make the Irish grow civil, and become English.” By 1620, it was with some relief that colonist and judge, Luke Gernon, expressed his belief that the Irish were now exhibiting all “the symptoms of a conquered nation.”

The planting of Ulster, undertaken by the English, Scots, Welsh and loyal Irish to whom James referred to as “the British undertakers and servitors” had, according to his officials, began to realize James’ vision for a new “British” society.

Whilst Sir Francis Bacon and John Davies undoubtedly painted a deceptively rosy picture of success in Ireland, society slowly seemed to be becoming less lawless. However, the lingering grievances of many sectors of the population would come violently to a head in decades to come, leaving thousands dead on both sides.

__________________________________

From The Sun Rising: King James I and the Dawn of a Global Britain, 1603-1625 by Anna Whitelock. Copyright © 2025. Available from Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Anna Whitelock

Anna Whitelock is a historian, author, and broadcaster. She is professor of the history of monarchy at City St George’s, University of London and director of the Centre for the Study of Modern Monarchy. Whitelock is an international media commentator on monarchy, public history, and heritage, as well as on the Tudor and the Stuart dynasties. She is also the principal investigator on a major Arts and Humanities Research Council project, The Visible Crown: Queen Elizabeth II and the Caribbean, 1952 to the Present. She is the author of Mary Tudor: England’s First Queen and The Queen’s Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth’s Court.