When Disability Rights Activists Staged a 25-Day Sit-in at a Government Building (Alongside the Black Panthers)

Judith Heumann and Kristen Joiner Recount a History-Making Protest

“If I didn’t fight, who would?’”

One of the most influential disability rights activists in US history tells her story of fighting to belong.

Judy Heumann was only five years old when she was first denied her right to attend school. Paralyzed from polio and raised by her Holocaust-surviving parents in New York City, Judy had a drive for equality that was instilled early in life. In Rolling Warrior, Heumann shares her journey as an activist, ultimately leading the famous Section 504 protest, the longest nonviolent sit-in at a federal building in United States history. In 1977, over 150 disabled people occupied a government building in San Francisco for 25 days. Their demand was that the Carter administration sign Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, a groundbreaking piece of legislation mandating that disabled people could not be “excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program of activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” It was the first bill to acknowledge that discrimination against disabled people existed and to make it illegal.

*

“Judy! Judy! Wake up!” I opened one eye.

A shot of adrenaline spiked through my body. A monitor was standing in front of me, a serious look on his face.

“What’s happening?” I looked at my watch. It was six in the morning. Next to me, Jim sat up.

“The security guards aren’t allowing anyone into the building. People can leave, but they can’t come back in. Nobody can come back in. Judy, I think they’ve been ordered to completely shut down the building.”

I looked at Jim and then back at the monitor.

It was Easter weekend, which meant that people would want to go home to see their kids. Not to mention the fact that this also meant no food, no medications, no change of clothes could be brought in—nothing.

“People are going to start leaving,” I said.

Jim and I went to assess the damage.

The hot water in the bathrooms was shut off. The office phone lines had been blocked for outgoing calls. Our only means of calling the outside world was two pay phones in the hallway.

Califano was squeezing us out.

We listened to the news.

“By now this demonstration here in San Francisco is clearly symbolic,” said one reporter. “The group which left the Washington DC offices of HEW yesterday afternoon were the only ones who really had direct access to Secretary Joseph Califano. Any demonstration here in San Francisco, well, can only be to show support. But it can’t do anything tangible to get that anti-discrimination law signed right now.”

We were being dismissed. Again.

And the day was just beginning.

*

“HEW is not studying the regulations, anymore,” said a woman who worked in Congress and who had sneaked in the day before. She’d brought news.

“Califano is working on a major redirection,” she said. “They have a list of issues. They’re looking at potentially excluding a whole bunch of buildings and creating some sort of university consortium that allows colleges to avoid becoming accessible. It would essentially require disabled students to attend classes at only certain universities.”

The news hit us like a ball full of lead.

Finally, Pat spoke. “It is still separate but equal in a new form.”

“They’re not taking us seriously at all.” Kitty said what we were all thinking.

Not long after that, we got news that Denver and New York City had folded. The protesters had had no personal assistance or accessible bathrooms.

It was down to us and Los Angeles.

Sitting in Maldonado’s office, looking at the somber faces around me, I felt like we were on the edge of a deep dark pit.

All of a sudden, a member of the outreach committee burst in.

“The governor of California wrote a letter to President Carter urging him to sign the regulations! We’re getting help from all kinds of civil rights groups! The United Farm Workers sent a telegram of support signed by Cesar Chavez himself!”

We stared at her, unable to process what she was saying. The governor of California? And Cesar Chavez, as in the famous civil rights leader for farmworkers? That Cesar Chavez?

We lifted our arms and cheered.

People were paying attention. They were listening. They supported us.

We just had to hold on and figure out how to turn up the volume on Califano.

We decided to go over Califano’s head. We would try to get to President Carter.

*

The protesters filed into the conference room. People were starting to look a little unwashed and ragged. Everything depended on our ability to convince them to stay. We waited until every single person had arrived and the sign language interpreters were ready to start translating.

When it was quiet, I began to speak.

“The situation is this. President Carter knows where we stand. The White House is supposed to be calling us. The call has not come through yet. The shutdown is serious, but we are gaining momentum. In the last few hours, we’ve been getting national attention. An endorsement from Governor Brown has just come in. We cannot leave. LA is the only other sit-in still going, and they’re holding on with just thirty-five people. We’re the biggest. We are asking if you can you stay. Can you? Every day will make a difference.”

Please stay, I thought.

One by one, people raised their hands. They offered help.

“I can call the Black Panthers,” said Brad Lomax, a young protester with multiple sclerosis. Brad used a wheelchair and favored suits with wide lapels. He was a member of the Black Panthers, who were Black revolutionaries famous for organizing in the Black community and protecting people from police brutality.

One hundred twenty-five protesters committed to staying.

I felt like we were in an enormous hot-air balloon that had almost crashed and then, out of nowhere, had been lifted by a massive gust of wind.

I started breathing again. Inadvertently, my brain shifted to the next problem.

How were we going to feed everyone?

*

We reconvened in Maldonado’s office. I had to stop and get some water. I hadn’t eaten for days. I was running on adrenaline.

“The shutdown is serious,” I said.

Then Kitty asked something I hadn’t thought about yet. “How are we going to stay in touch with our allies and the press?”

It was a good question. If we weren’t in the news, we’d become irrelevant. Califano would win.

Then, someone, I don’t remember who, had a brilliant idea: sign language.

We gave our announcements and messages to the deaf protesters. They took them to the windows looking out on the plaza where our supporters were holding a vigil. Once they got the attention of the deaf protesters and sign language interpreters outside, they signed our messages through the window. The deaf protesters and sign language interpreters then relayed the messages to the right people.

It was the perfect secret weapon.

*

Later that afternoon, we were in Maldonado’s office trying to figure out food for our extremely large group, when one protester came rolling in fast.

“The Black Panthers are forcing their way into the building!”

Zooming out of the office, we rolled down the hallway just as the fourth-floor elevator doors slid open. Six tall men walked off the elevator carrying tubs.

“We’ve got dinner and snacks here,” one of them told us. He was wearing a black leather jacket and a slouchy hat. “We told the security guards we’d stop at nothing to bring the media’s attention on HEW if they didn’t let us in and you guys got starved out.” The Black Panthers had pushed their way into the building with fried chicken and vegetables, walnuts and almonds—food for all 125 of us. We gathered around and clapped.

The Black Panthers would bring us food every night for the rest of the protest.

That night, the news came out.

“They’re tired. They’re grubby. They’re uncomfortable. But their spirits are soaring. The sit-in in the San Francisco HEW headquarters is now in its third day. A hundred and twenty-five disabled and handicapped are pledging they’ll continue the sit-in through tomorrow night, if not longer. The squeeze is on, though. Hot water has been turned off on the fourth floor, where the occupation army of cripples has taken over.”

__________________________________________________

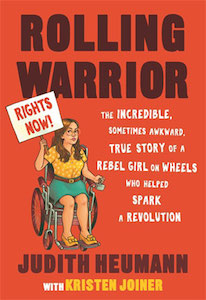

Excerpted from Rolling Warrior: The Incredible, Sometimes Awkward, True Story of a Rebel Girl on Wheels Who Helped Spark a Revolution by Judith Heumann and Kristen Joiner (Beacon Press, 2021). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.