When Cause Doesn't Follow Effect: How to Structure the Strange

Rebekah Bergman Recommends Innovative Ways to Build Your Next Story

I gravitate toward fiction that some might call strange. I like stories that are free from the logic that governs our reality. Who says time—in fiction—must move forward smoothy and in one direction? Who says effects must follow clear causes? I also love when writers innovate with structure, stretching what a storyteller can do with form.

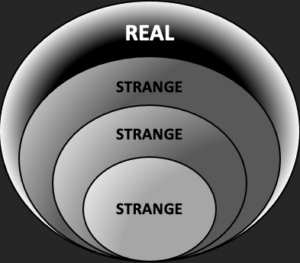

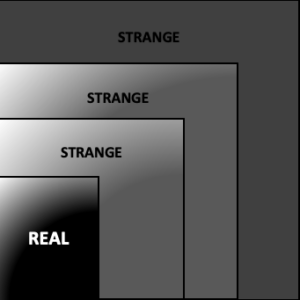

In 2015, as I worked to complete my MFA in fiction, I began an investigation. I wanted to better understand how these two elements—structure and the strange—can combine. How might the unreal overlap with, blur behind, or nest inside the real? And what can a writer achieve by structuring the strange in innovate and intentional ways?

At some point while taking notes on the stories I read, I started sketching. I’m not a particularly visual person, but I felt like a simple illustration might help me better approach these questions. I began creating basic maps of how the stories were operating.

These diagrams of the strange have been incredibly instructive in my writing process. They’ve showcased the diverse ways the real and the strange might collide in fiction and how those collisions can represent elements of our strange, real world.

Below are three of my favorite strange stories and the insights I’ve gained by creating diagrams for each of them.

*

Structure #1: Carmen Maria Machado’s “Inventory”

In this story, the strange is a blurred background that a reader needs to pay close attention to in order to see.

The narrator of Carmen Maria Machado’s “Inventory” creates a list of everyone she’s ever been intimate with: “One girl,” she begins. “We lay down next to each other on the musty rug in her basement.”

How might the unreal overlap with, blur behind, or nest inside the real?

The physical details of each itemized encounter are rendered in sharp focus: “Round glasses, red hair;” “Six inches shorter than me;” “Blonde hair, brash voice;” “Slender, tall. So skinny I could see his pelvic bone.”

A reader must turn their eye away from these bodies to see what else is happening. Where is the narrator in the present moment that she is recounting this list? In rare, short asides, the narrator mentions a few details: that she misses the smell of fabric softener, that she will probably never get to see the movie Jurassic Park. Through these and other details, it slowly becomes evident that a pandemic virus, spread through human contact, is ripping across the nation.

With this context, the inventory of intimacy takes on a powerful weight. Machado’s structure foregrounds common elements of our conventional reality—the experience of having a body, of intimacy and relationships, and, when they end, of being left with only one’s memory of those intimacies and relationships.

But by placing these aspects before their apocalyptic backdrop, Machado is able to speak to a broader and much stranger aspect of our very real world. She reminds us how the normal parts of life can—and so often do—keep going right up until they hit against a nightmare that has been unfolding in the background all along.

Structure #2: Kelly Link’s “Lull”

This second diagram depicts Kelly Link’s “Lull,” an intricate, Russian doll of a story.

“Lull” is a difficult story to summarize. There are four nested narratives within it. One is told by a phone sex operator and features a cheerleader at a high school party with the devil. In the world of that story, time moves backward. Another is told by the cheerleader.

At the outside of all of that, though, at the very first layer of “Lull,” is a comparably more realistic entry point. A middle-aged man named Ed is hanging out with his buddies. One of them is a mean drunk. Another puts pepper on everything he eats. All of them are preoccupied with the passage of time and their regrets. And Ed—who seemed to have a perfect marriage—is getting divorced.

It’s this realistic premise that gives birth to the strange, which gives a new strange shape to the real. Link completely subverts the logic of cause and effect. She subverts the very notion that plot must move characters forward in time and space altogether. The cheerleader in the second layer moves backward and the main character, Ed, hardly moves at all since; the nested stories unfold filling a lull in conversation at a poker night.

Nonetheless, by the end, when we exit all those layers and catch back up to Ed and what the future might hold for him and Susan, if there is a future at all, he is changed. We can see it. Each layer of the story has brought him—and the reader with him—deeper into his psyche. He has gained a better understanding of went wrong in his marriage; it was a matter of timing, sure, but also a trauma that everyone in Ed and Susan’s life can only—fittingly enough—circle around.

Structure #3: Alice Sola Kim’s “Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters”

This last diagram—Alice Sola Kim’s “Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters”—combines some elements of the previous two. I like to view this map like a series of doors, each opening to a larger door, on and on.

“Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters” is a time travel story and like most time travel stories, something goes wrong. Hwang, the protagonist, wants to travel to the past save his daughters who were kidnapped, but he can only go to the future. Every time he falls asleep, unwittingly, he jumps forward.

The story is somewhat list-like, and in that way reminiscent of “Inventory.” Each time Hwang jumps, the narrative moves to a new section of text. The jumps may cover a few days or a hundred years. In both “Inventory” and “Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters,” the sections are attempts to reclaim what is lost; intimacy in Machado’s story, family in Kim’s. In both cases, the structure reiterates the failures of these attempts. Just as each lover is already an ex-lover, each section ends when Hwang, inevitably, falls back asleep.

Like “Lull,” there is also an embedded nature to Kim’s story. The past is nested inside the future after all. Each time Hwang jumps forward, he reaches a new generation that was born from the previous generation. The women he meets are not his daughters; they are his daughters’ daughters’ daughters. Where I placed “the real” on the very outside of Link’s story, in Kim’s it is right at the onset.

The difficulty in diagramming this story is that the real and the strange are not as clearly distinct as in others. The lines blur. The strange futures Hwang finds himself in are not entirely far-fetched or unrealistic; there are aspects of the real inside them.

In one future, gene therapy makes sleeping unnecessary, but the therapy is too expensive for almost anyone to afford. “[I]t is the rich who do not have to sleep.” In another, Hwang “arrives at a time when everyone is green.” In a parenthetical aside, the narrator comments, “Don’t worry—there is still racism!”

I am certain that my work of diagramming the strange in other authors’ stories opened new possibilities for me.

These and other satirical references to very real social and racial issues make the strange futures seem, as cynical as it is to say, if not real then realistic.

There are also wonderful moments when the satire dissolves, and details resonate with genuine truth about the strangeness of our actual world. “Hwang tries to look at it this way: time jumps forward when you sleep no matter who you are.” This line turns the completely familiar act of sleeping into a strange process of time travel.

The complex structure and clever satire of “Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters” give the story its power: making the strange shine for its plausibility, and making the quotidian feel utterly strange.

*

Over the years, diagramming the strange has invigorated my reading and fueled my writing. I’ve come up with writing prompts inspired by the different maps I’ve made. From those prompts, I’ve produced sketches, drafts, and scenes that have helped me get unstuck when I’ve needed it. At least one of those sketches eventually found its way into my debut novel, The Museum of Human History.

My novel centers on a girl who falls into a coma and stops physically aging. It follows several different characters who find themselves drawn to her as they each grapple with very real issues of being bound in and by time.

While writing and revising, I actually never sat down to create a diagram for it. This is probably for the best since the novel’s final, full structure didn’t reveal itself until relatively late in my process.

But I am certain that my work of diagramming the strange in other authors’ stories opened new possibilities for me as I worked on my book. I wasn’t consciously emulating Kim or Link or Machado, but I was nonetheless influenced by their and other writers’ diverse and distinct answers to my initial questions about how the unreal and the real might—as they so often do—intersect.

More strange stories to read and diagram:

“Suburbia!” by Amy Silverberg

“The Rememberers” by Aimee Bender

“Edna in Rain” by Marie-Helene Bertino

“An Index of How Our Family Was Killed” by Matt Bell

“The Knowers” by Helen Phillips

__________________________________

The Museum of Human History by Rebekah Bergman is available from Tin House Books.

Rebekah Bergman

Rebekah Bergman’s fiction has been published in Joyland, Tin House, The Masters Review anthology, and other journals. She lives in Rhode Island with her family.