When Bruce Lee Trained With Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Jeff Chang on What Two Iconic Athletes Learned From Their Collaboration

When Bruce Lee met Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a month after the 1968 national college basketball championship, he was still known as Lew Alcindor, the most hyped young basketball star in history.

Lew was seven feet two and, for his whole life, had been unable to hide. He disarmed reporters with a fierce intelligence masked by a laconic intensity. He was just completing his junior year at UCLA, and after indulging in two years of partying, drugs, and women, he wanted something different. “All sophomore and junior years I’d been looking for something to believe in,” he would later write.

During those two years, he had been in the eye of the storm. In the “Game of the Century,” witnessed by fifty-two thousand in the Houston Astrodome and millions more on television on January 20, 1968, he brought men’s college basketball to new heights. That night he played with blurred vision after having his cornea scratched. UCLA lost by a basket to the University of Houston, breaking their forty-seven- game winning streak, and the team melted down in its aftermath. Lew’s closest friend, a Black man from South Central Los Angeles, quit the team in a dispute with coach John Wooden, and racial tensions simmered in the locker room the rest of the season.

To him, Bruce was as effective a teacher as John Wooden. Both were focused on fundamentals, preparation, and what worked.

By the end of the season, Lew had led UCLA to its second consecutive national championship and was voted Most Outstanding Player for the second year in a row. It was the year that began the “March Madness” era. But after the season, he retreated.

Born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor in 1947, the day after Jackie Robinson desegregated pro sports, he had grown up in an integrated housing project in uptown Manhattan. In third grade he stared at a Polaroid of his class: “There I was, freakishly towering over all the other kids, with skin much darker than everyone else’s.” When he was twelve, his white friends abandoned him. His former best friend picked a fight with him one day, calling him a “jungle bunny” and “big jungle n——r.”

At seventeen, Lew stepped out of the subway in Harlem and was caught in the first hours of six days of rioting that followed the police shooting of a Black teen. As bottles and bullets whizzed by and buildings went up in flames, he ran home. “Right then and there I knew who I was and who I was going to be. I was going to be Black rage personified, Black power in the flesh,” he later wrote. He led his team to a 79-2 record and two national high school championships. But once, to motivate him in a game, his coach had called him a “n——r,” and he never forgot it.

In his sophomore year at UCLA, in 1967, he was traveling with extra security because of death threats. He took comfort in listening to hard bop and reading about African and Asian history and religion. He was particularly captivated by The Autobiography of Malcolm X and the late Black leader’s journey into Sunni Islam, and sought out young Black Muslims in Los Angeles.

That summer he was the only college athlete among a group of prominent Black athletes invited by Jim Brown to meet with Muhammad Ali to try to change the boxer’s mind about his anti-war stance. Ali had asked, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” After declaring, “I don’t have no personal quarrel with those Vietcong,” he saw his heavyweight boxing title revoked, and faced a prison sentence for draft evasion. The men spent hours grilling Ali on his position, then emerged to face the press. Alcindor sat beside Brown, Ali, and Bill Russell as the athletes joined together in a historic show of solidarity for Ali.

Invited to a Black Youth conference by a young San Jose State College professor named Harry Edwards, who was organizing a Black athletes’ boycott of the 1968 Olympics, Alcindor spoke with conviction:

I’m the big basketball star, the weekend hero, everybody’s All American. Well, I was almost killed by a racist cop shooting at a black cat in Harlem. He was shooting on the street—where masses of people were standing around or just taking a walk. But he didn’t care. After all we were just n——rs. I found out that we don’t catch hell because we aren’t basketball stars or because we don’t have money. We catch hell because we are black. Somewhere each of us has got to make a stand against this kind of thing.

But in the media, an explosion of racist invective followed him and other Black athletes as they were accused by white writers of being ungrateful, unpatriotic, uppity “Black Hitlers.”

*

Weeks after the 1967 championship, the NCAA banned the dunk—in what became known as the “Alcindor rule”—an effort he believed was racist. Forced to improvise, he contemplated how to deal with triple-team defenses and worked on a new offensive weapon: the skyhook. One night after watching a Zatoichi flick, he was struck by the idea that the blind swordsman’s grace, control, and precision might be exactly what he needed. Instead of brute force, he thought, I will slide and roll and slip by them without fouling. In New York City, Alcindor started training in aikido.

“A victory [in martial arts] is your mind over someone else’s mind, as much as, if not more than, a simple physical mastery,” he later wrote. “The discipline also becomes a means of staying in shape mentally and keeping your entire inner self trained.”

That fall Alcindor visited the Black Belt offices to meet a fellow aikido adept, Mito Uyehara, and ask him if he knew someone with whom he could continue his martial arts training. Alcindor had become especially curious about tai chi. “This guy Bruce Lee—he’s really good at it,” Mito told him. “He knows more about those things than I do.”

“Who’s Bruce Lee?” Alcindor asked. “He was Kato in The Green Hornet.”

Alcindor was skeptical he could learn anything from an actor. “No, no! He’s the real deal.”

That night Mito drove to see Bruce and said he was sending Lew Alcindor over. “Who’s Lew Alcindor?” Bruce asked.

Mito explained that he was the tallest and most famous college basketball player in the country.

“I don’t watch basketball.”

Bruce asked Linda to bring a tape measure, stood on a chair, and dropped it down, to visualize Alcindor’s height. Then he thought aloud, “I wonder how fast he is.” Mito assured Bruce he was very fast, one of the best athletes in the world.

“He would have no chance with me,” Bruce said with a chuckle. “I would break his legs before he could do anything else.”

*

They met for the first time at Bruce and Linda’s house on a comfortable Los Angeles afternoon.

“He greeted me with a broad smile and friendly demeanor and right away I knew this was not a scowling teacher from Japanese films demanding bowing obedience,” Alcindor recalled. “We talked UCLA basketball for a while and then got down to business.”

Bruce first had Lew punch and kick the heavy bag, so he could gauge the big man’s power. Then he called Linda over, asked Lew to hold a pad to his chest, and told Linda to kick it. Linda grinned and got up from the patio seat where she had been watching.

“Bruce, I don’t think this will work,” Alcindor said. “I’m two feet taller and a hundred pounds heavier than Linda.”

“Just hold it up to your chest, Lew,” Linda said.

He lowered the pad so that it would be below her head.

“Your chest,” Linda said, frowning and pointing at the pad. “Do you want Bruce to show you where that is?”

He moved the pad up. Bruce nodded at Linda. Kareem would never forget what happened next.

“Suddenly Linda fired off a kick that not only reached the pad, but the impact rocked me backward a few feet, readjusted my spine, and possibly rearranged the order of my teeth,” he remembered. “They stood there smiling at the shocked expression on my face.”

Linda—Bruce’s longest-running student except for Taky—had just done what Bill Walton, Happy Hairston, Kent Benson, and Robert Parish never would.

“Okay,” Alcindor said, still sore where she had kicked him. “Teach me that.”

Bruce was just as intrigued. Not long afterward, he told Leo Fong, “You know why I’m getting him to train with me? I want to learn how to beat a tall guy!”

*

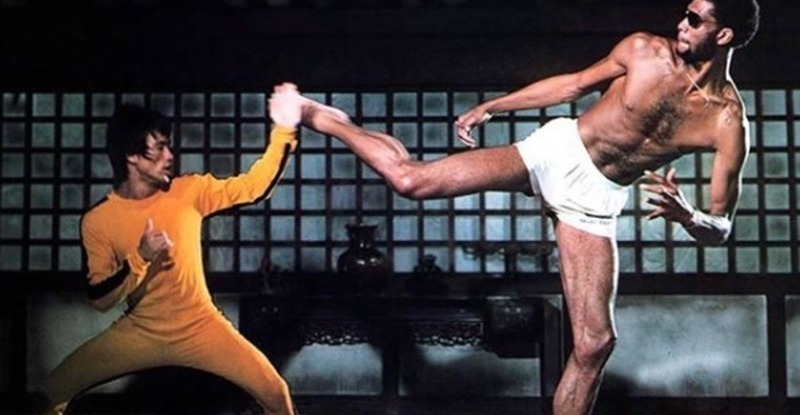

“Big Lew,” as Bruce called him, came to his backyard every Tuesday during the off-season, and sometimes Thursdays as well. Bruce taught him Jeet Kune Do footwork, the mook jong dummy, and punches and kicks on the bag. At first, Bruce told Mito that Big Lew was slow, his arms were weak, and he wasn’t good at chi sao. A reporter who witnessed one of their workouts was more impressed with Bruce than Big Lew. He wrote that Bruce could “leap and kick over Alcindor’s head, and says he can defeat him by taking advantage of his shin and thigh with a kick.”

But Bruce soon realized all that was irrelevant. Even if he could get inside Big Lew’s reach, it wasn’t easy. And with his front kick, Big Lew could rattle the rim of the basket. Bruce’s Wing Chun skills were all but useless. He joked with Doug Palmer, “Try doing chi sao with someone when you’re staring at his belly button.” Bruce called Taky and told him not to focus on chi sao in the school anymore.

“Bruce and I sparred regularly,” Kareem remembered. “But we didn’t compete; I was like a drawing board on which he could work out his theories and he was instructing me how to deal with people and attack him.”

Kareem came to appreciate Bruce’s approach. “Nothing was for art’s sake. Everything he taught was to achieve an end in doing damage to an opponent,” he recalled. “After studying for a little while, you learn a lot about how easy it is to hurt someone, and how easily you can get hurt. That makes you really respect what you’re involved in. With violence, you learn to respect it and see how easily you can become victimized by it.”

To him, Bruce was as effective a teacher as John Wooden. Both were focused on fundamentals, preparation, and what worked. “Bruce used to say, ‘I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.’ In sports, we call this concept ‘muscle memory,’” he said. “For me, my hook shot was the one kick practiced 10,000 times.”

Bruce helped the young athlete understand his movements in a way that seemed to decelerate time. “Bruce showed me how to harness some of what was raging inside me and summon it completely at my will. The Chinese call it chi; the Japanese, ki; the Indians, prana—it is the life force,” he said. “I was quite amazed to find, after working with Bruce, that when I really had my presence of mind, when I did control my life force, that’s what I saw, things coming at me in slow motion with plenty of time to get out of the way.

Bruce helped the young athlete understand his movements in a way that seemed to decelerate time.

“It sounded mystical when he first told me, but I was becoming increasingly involved in matters of faith, and besides, Bruce grounded his philosophies in a good fight, which I could relate to.”

*

These sessions were a refuge from the media, who were painting Lew Alcindor as a coddled, ungrateful, unpatriotic athlete. In July 1968 he had agreed to an interview on the Today show to highlight the summer program for Black youths where he was working. But sports announcer Joe Garagiola ambushed him, asking Alcindor why he had declined to play in the Olympics. “You live here,” Garagiola said.

“Yeah, I live here, but it’s not really my country,” Alcindor answered. “Well then, there’s only one solution: maybe you should move.”

“Well, you see,” Alcindor responded, heating up, “that would be fine with me, you know, it all depends on where we are going to move?”

The producers cut away to a commercial.

“I felt no part of the country and had no desire to help it look good,” he later recalled. “I had better things to do.”

That summer he joined a mosque, declared shahada, became a Sunni Muslim, and received a new name: Abdul-Kareem, later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, “noble, generous servant, powerful spirit.” He kept his name to himself and his closest friends until he asked the media two years later to call him by it. He recalled, “I was still Lew to almost everybody, as if I knew them but they didn’t know me….

“The heat I’d taken about the Olympics, and the absolute unwillingness I’d found in the press, and by extension the general public, to accept what to me seemed so obvious—that the country was run by white people for white people, and that even the most powerful Black men were still operating at a handicap—made me suspicious of strangers and even more jealous of my privacy.”

But with Bruce, everything was easy. The two talked philosophy and religion. They went to see Zatoichi flicks. Kareem even babysat sometimes, lifting Brandon up to give the five-year-old a view of the roof. They shared an understanding of fame and privacy. From youth, both of them had been under the spotlight.

In Chinatown they never paid for meals—everyone was a UCLA fan—and they often ate in the kitchen. Bruce joked to their companions that it would guarantee they weren’t getting the garbage served to the gweilo. But Bruce was also shielding the big man from the rabid autograph seekers.

“Bruce and I had something else in common,” Kareem recalled. “We both had experienced discrimination.”

Kareem talked about the Black liberation movement and his role in what Harry Edwards had come to call “the revolt of the Black athlete.” Bruce shared his frustrations with Hollywood, saying he sometimes felt like a “valet to the stars.” They swapped books. Bruce gave Kareem Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings. Kareem gave him books to read on Islam and imperialism. He told a shocked Bruce that Europeans had barred Chinese from parks in their own cities.

“I recommended certain books about the British occupation of China,” Kareem said. “He didn’t know anything about that, and he’d gone to school in Hong Kong.”

__________________________________

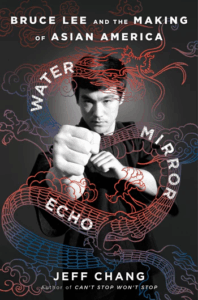

Excerpted from the book Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America by Jeff Chang. Copyright © 2025 by Jeff Chang. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Jeff Chang

Jeff Chang’s first book, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, was named one of the best American nonfiction books of the last quarter century. He has been a USA Ford Fellow in Literature and, among numerous other honors, has won the American Book Award and the Asian American Literary Award. Chang has written three other acclaimed bestsellers on American history and culture, music, and the arts. In May 2019, he and director Bao Nguyen created a four-episode digital series adaptation of his award-winning book We Gon’ Be Alright for PBS Indie Lens Storycast. Chang was featured in Nguyen’s ESPN Bruce Lee documentary, Be Water; the PBS series, Asian Americans; and Lisa Ling’s CNN series, This Is Life.