When Activist Poets Took Over a Tiny California Town

Uncovering a Unique Chapter in the History of American Poetry

Beginning with the phrase “Chant’s Operation,” Tom Clark’s poem “Inside the Dome of Taj Mahal” seems to use aleatory juxtapositions to disrupt the concentration necessary for a successful chanting session. Claims about the absorbing natural beauty of the site where the poem was written—Bolinas, California, a mesmerizingly gorgeous small town overlooking the Pacific Ocean on the south end of Point Reyes, north of San Francisco—emerge as a voice-over whose authority can’t be trusted: “in nasal reef-voice, ah harmony / shimmering beyond choice.”

Though an active advocate of the community (Clark wrote numerous letters tofriends encouraging them to visit or move to Bolinas), he could also poke some fun at life there. Before concluding with a recommendation about soundtracks perfect “if you just want to drift off and disappear,” however, the poem also samples the line “the condition my condition was in,” from the 1968 Mickey Newbury hit “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition WasIn).” Clark often incorporates rock lyrics into his poems.

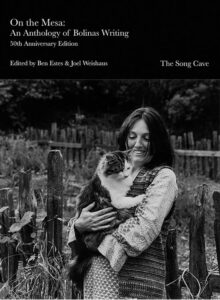

This line, though, offers us a viable microcosm of the problems that confront us when we try to study the Bolinas community, the scene represented in On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing, first edited in 1971 by Joel Weishaus and published by City Lights, now re-released in a 50th anniversary edition edited by Ben Estes, which includes 66 new poems by 19 writers not in theoriginal anthology. Most of the poets who wound up there were coming down after a long decade of constant and often taxing activity: from full-on activism and small press publishing to around the clock socializing and grueling daily lives in cities that were seeming less and less livable—stress factors obviously varying poet to poet, whose involvement with activist politics (and with these other activities) also varied. Still, it is safe to say that the many poets who arrived in Bolinas from San Francisco, New York City,Buffalo, Albuquerque, and elsewhere were often, like the singer of “Just Dropped In,” a bit dazed, badly overdue for scheduled maintenance—a “condition” indicated by the logical hiccup of the song’s title.

But for those who missed the 60s themselves, “Just Dropped In” likely takes us back to the way they were framed by Hollywood in 1998, the year the song guided the bowling dream sequence of The Dude (Jeff Bridges) in The Big Lebowski. Here the song’s quaint psychedelic ambiance becomes just further evidence of the Dude’s delusional bad taste— like his bowling, his sweater and legging ensembles, his mumbling and, worst of all, his Students for Democratic Society past. Whatever slogan about “the system” or“change” a hippie student might have yelled in the heat of a rally, finally the ‘60s were about the process of becoming more attentive to“the condition” each private subject’s “condition was in.” As Bill Clinton continued the Reagan project of eviscerating the state, thiswas increasingly how ‘60s radicalism was coming to look to the practical realists of 1998, about when I began researching Bolinas.

Clark’s poem was included in (but missed when I wrote about) the original On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing. The importance of these numbers, and more importantly the careful selection behind them, is that they flesh out what was a fascinating if incomplete document into a more self-contained and usable picture of one of the great countercultural experiments of the later 20th century, the poet-run town of Bolinas.

It is safe to say that most poets, literary scholars and even cultural historians remain unaware of exactly what American poets undertook in Bolinas. But imagine a city of about 500 people basically run by poets. No, it was not as dysfunctional as the image that just flashed into your brains: buildings aflame above monumental piles of uncollected garbage with a distant circle of hippies, unaware, out smoking weed on the nighttime beach. There were problems and conflicts, to be sure, but also a lot that transcended our received image of the 60s as an era simply about personal visions, indulgent drug use, and narcissistic and finally destructive attempts at self-care.

Instead, poets in Bolinas sought to create an ecologically sustainable town where anyone could be an agent of news-making. Aware of their amazing natural resources—the views, the air, the sun, the northern Californian smells—they worked toward keeping these aspects of the town collective, and not privatizing it. They conceptualized poetry as a way to help focalize this present and its pleasures. And to do this the Bolinas poets also had to put some pressure on our familiar models of who gets to be a poet, and who a follower: while hierarchies wouldn’t simply and finally disappear, the poets in Bolinas went quite a ways toward democratizing writing as a widely shared activity, and not only the province of isolated, revered stars—though there were some of these here as well. Poetry, we might say, wasn’t just a shared interest among many of Bolinas’ citizens; it was the organizing feature of daily life in the town, where most of the poets could survive on part-time, comparatively non-alienating jobs, or even on unemployment. Though it wasn’t discussed much explicitly, we might see the attempt to reorganize time in places like Bolinas as part of a wider counterculture process of turning off or rejecting national time, with its labor/leisure division enforced by the work day and its building up of units of attention by the media, in particular the half hour and hour slots that were coming to rule so many American homes through television and radio.

Unknown Photographer, 4th of July, 1971, Bolinas Museum Archives.

Unknown Photographer, 4th of July, 1971, Bolinas Museum Archives.

The Bolinas attempt to put poetry at the center of this town was and wasn’t singular. It emerged in part as a response to earlier American poetries of place, by which I mean not individual poems conceived of in relation to specific locations, but rather larger-scale projects that turned to place not merely for descriptive but also for social and historiographic purposes. I’m thinking in particular of what would have been for the Bolinas writers the two key American precedents, William Carlos Williams, and his Paterson (1946-1958, organized around the town in New Jersey) and Charles Olson, and his The Maximus Poems (1953-1970),based on Gloucester, Massachusetts. Both of these large, ambitious experimental poetry epics studied the histories of specific locations in order to trace out other, more capacious histories of the New World that might in turn sustain different kinds of social life, and social belonging, in the present. They were counter-nationalist epics.

But the key difference between these two works and those undertaken by the wide range of poets in Bolinas is not only the diffusion of the singular project into that of an entire town; it was also that whereas for Williams and Olson the writing and research were directed toward readers in the future who might, they hoped, make good on their results, for the Bolinas poets there was an attempt to mobilize a place-based writing immediately—right now, in the present, and for themselves. As Clark put it, “No more rehearsals.” In this sense Bolinas could be compared to a range of other attempts in the 1960s—all aligned with the New Left in various ways—to actualize or enact place-based social formations.

These would include Gary Snyder’s familial compound in Kitkitdizze, where the poet designed a polemically extreme ecological structure for his family (no enclosure that would keep insects out, for instance) as a kind of essay about place-based living. They would also include Amiri Baraka’s development of place-based living in Newark, after his moves—first from the downtown Manhattan Bohemian scene of the early 1960s to Harlem, and then from Harlem back to his hometown. There, Baraka was central in establishing Spirit House, a Black Nationalist collective that offered a complete re-education for African Americans, from food and clothing to music and poetry to politics and history.

By these standards the Bolinas experiment was not as thoroughgoing or organized, and no doubt would have been sneered at by many radicals in 1971, including Baraka, especially because his whole project involved a return to urban spots deemed unlivable and institutionally abandoned in part because the tax base was fleeing from the cities. From this angle Bolinas was part of the larger white flight phenomenon; the hippie community there was composed largely of white New Yorkers and San Franciscans who had found the cities unpleasant and had the means or contacts to escape. But the entire Bolinas project cannot just be dismissed in such broad sociological strokes—especially when popular culture urges us to be ungenerously impatient about such undertakings like this as well.

When I first started seriously researching late 60s poetry and Bolinas, I was drawn to it not just as an alternate community but as the only instance I could think of where a town was essentially governed by poets. That so many poets I was interested in were part of the experiment added another enticement. Bolinas seemed less like an important though undocumented moment in American poetry history than like a fantasy alternative history—one that hadn’t really happened, but was fun and maybe even instructive to imagine. While On the Mesa was a point of departure, it was, as mentioned, an incomplete view: you simply couldn’t understand the social dynamics of the place unless you read Joe Brainard’s brilliant Bolinas Journal, for instance. Ted Berrigan’s “Things To Do in Bolinas” also helped. Neither was included in the original anthology. Nor were Alice Notley, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Duncan Mc Naughton, Aram Saroyan, Jim Brodey, Diane Di Prima, Philip Whalen, Anne Waldman, Phoebe MacAdams, Jim Carroll, Richard Brautigan, Gailyn Saroyan, Stephen Ratcliffe, Lewis MacAdams or Charlie Vermont.

But all these poets had been there, and had written about it. I did not get to all of them during my own research—which involved a pretty crude (pre-easily searchable web) attempt to comb through period books from likely suspects and put the pieces together. So I all the more appreciate Ben Estes’ thoroughness and care in adding these names and pieces of writing to our available Bolinas history—housing them conveniently as a new series of verandas on the original west coast bungalow of 1971.

The writing I ultimately composed—“Non-Site Bolinas: Presence in the Poets’ Polis”—was a chapter in my 2013 book Fieldworks: From Place to Site in Postwar Poetics. I won’t try to replicate it here. Let me instead close by expressing optimism about both the simple fact of the reissue of this anthology, and the even more surprising expansion of what can now count as the Bolinas scene. This bodes well for those in the future, or right now, who would like to dive into actually thinking about both the counterculture and the poets’ intimate ties to it. We have been offered more than enough tools for distancing ourselves from the ‘60s, for ironically undercutting “hippie” aspirations; it is therefore rare and wonderful to have an anthology like this placed before us—one that makes the past of 50 years ago look fresh and strange and attractive.

__________________________________

Adapted from On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing (50th Anniversary Edition), published by The Song Cave.