A few old-timers of Hartford’s North End vaguely remembered Elijah Muhammad preaching his “white man is a devil” credo, which had fallen on deaf ears during the booming wartime years. Having fled a bare-knuckled, violent racism in the South that was unimaginable in New England, blacks were brimming with the migrant’s sense of optimism in their adopted city, with its better-paying jobs and desegregated schools.

No doubt recalling his chilly reception there, the Messenger dismissed Hartford to his young Hotspur as a total waste of time. Nonetheless, Malcolm had pressed for permission to pursue Mrs. Glover’s invitation. Muhammad had given the go-ahead more with a sense of indulgence than with any expectation for success in Hartford. After all, the Negroes of Hartford had essentially thumbed their nose at the Messenger himself.

The challenge was not lost on the highly competitive Muslim disciple on the move.

*

On that initial Thursday in 1955, Malcolm was lighting out for new territory. The fair-skinned and graying Mrs. Glover greeted him with an easy smile at the door of her spruced-up flat in the Bellevue Square housing project. Other than hearing the rumor that food and soft drinks would be served, some of the dozen or so invited guests had only a vague notion about the purpose of the gathering.

A gentle curiosity hung in the air as Malcolm sized up the North End strangers and folded his lean frame onto the living room sofa. “Thursday,” the Autobiography stated, “is traditionally domestic servants’ day off. This sister had in her housing project apartment about fifteen of the maids, cooks, chauffeurs and house men who worked for the Hartford area’s white people.”

Reaching for the snacks, Mrs. Glover’s neighbors gazed upon the stranger from Harlem, easing into his riff about how divided Negroes were in America generally. Switching gears, Malcolm got local and pitched the need for those in Hartford to unite on social, economic, and, yes, religious grounds.

Suddenly, the teenage daughter of the hostess felt tricked. In clear and secular language, she had demanded that the family spare her all religious events—especially, any contact with preachers. Unlike her two younger sisters, this newly minted high school graduate had her own apartment, a few blocks away. As a nod to her mother, this namesake daughter, Rosalie, had stopped by after work from her job at Connecticut General Life Insurance Company.

But as the visiting minister continued his opening volley, the independent-minded young woman smirked her way backward toward the door. Something about this tall stranger, however, stayed her hand from the door knob. At first it was his neat, starched persona, his Lincolnesque chin, his golden hue, the horn-rimmed gaze of his light-colored eyes that held no doubt. The bright-eyed 19-year-old had encountered no other Negro radiating such confidence.

Avoiding the intensity of his beam, young Rosalie peered at Malcolm from the side, coyly. He was stern yet gentle, “high-toned,” she sensed, yet quite earthbound, and flat-out reasonable—for a minister, that is. Her girlish eyes wandered playfully along the entire length of his body. The reverse usually was the custom, with the eyes of the smooth-talking preachers of her acquaintance doing the initial body scanning—sometimes accompanied by their roving hands, in a young lady’s unguarded moments. And now, here she was, struggling sheepishly to get herself under control.

Indeed, young Rosalie was fetched by the forbidding sensuality of the glib, lithe minister from Harlem. With only her tame high school experience as a guide, she picked up no incoming signal of interest, no traces, say, of the wanton lustiness of the Detroit Red of a decade ago. Although he was speaking easily about riding the New Haven rails through Hartford as a teenager, Malcolm skipped over his pursuit back then of the Gomorrah delights of Boston and Harlem.

As with Nation of Islam orthodoxy, Malcolm’s Muslim pitch was tilted sharply from the perspective of a dominant Negro male. He gave no hint that rapprochement between the black man and the black woman would be readily achievable, or even desirable. As Malcolm sounded the clarion, Mrs. Glover nodded agreeably and seemed prepared to sacrifice all, straightaway, for the cause of Islam.

The mind of her namesake daughter was someplace else entirely.

After an intense hour, Malcolm eased up, mindful of ending this initial lecture with an informal tone.Upon stressing that black men must respect and protect their women, Malcolm paused for dramatic emphasis as effectively as any stage actor. He then deadpanned, pointedly, that black women must earn that respect. Decked out in tight-fitting “short shorts,” young Rosalie froze at this riff. A rush of modesty shivered her momentarily. Struggling to regain her composure, she fidgeted, she folded her arms, and she tugged as best she could at the scant hem of the trendy red shorts riding well above midthigh.

Never had she felt quite this shamefaced in public. Although no one looked her way, she felt exposed in the crowded room—and yet, somehow, she felt alone. Young Rosalie would remember the poignancy of that 1955 moment decades later. The chaste baritone Malcolm had shamed her.

Her mother went busily about offering refreshments to the guests, occasionally forcing a smile, cutting her eyes over the room for clues as Malcolm roared on. The restless men in the rear grew rapt. This puzzled young Rosalie. She knew two of them as good-time Charlies prone to sipping Johnnie Walker Red at the nearby Subway Club on Main Street and chasing available ladies far into the night. There was at least one out-of-wedlock child. Yet the more Malcolm damned such behavior as abhorrent to black group advancement, the steadier this duo leaned forward in nodding agreement. It all seemed a tad surreal.

After an intense hour, Malcolm eased up, mindful of ending this initial lecture with an informal tone. The room came alive with questions. Someone asked whether Malcolm’s Muslims were affiliated with the Moors. As instructed by the Messenger, he assured the audience, somewhat inaccurately, that the NOI was not entwined with the Moorish Science Temple.

The tone of the visiting minister that day in Bellevue Square was strict, if not intimidating, to the carefree group. “He had a voice that could capture you,” young Rosalie said years later. “What he was saying wasn’t like anything I had heard before. I was really looking forward to him coming back again.”

That initial Thursday gathering in Hartford reminded Malcolm a bit of those times his father had hauled him around as a young lad to sessions held in Lansing, a similar capital city in the Midwest. Like his father, Malcolm dressed neatly, with his shoes shined to a high gloss. And while not balding as was Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm nonetheless took up his religious leader’s habit of always wearing a hat outdoors, the custom for so many gentlemen in that era. Over the coming months, during his visits to Hartford, he was seen sporting dark fedoras and occasionally even a French beret.

“You’ve heard that saying, ‘no man is a hero to his valet,’ ” Malcolm wrote in the Autobiography. “Well, those Negroes who waited on wealthy whites hand and foot opened their eyes quicker than most Negroes . . . every Thursday I scheduled my teaching there.”

As early as the second week, Lewis Brown, a local teenager, was approached by a white man in a dark suit with spit-shined brown shoes. He introduced himself outright as an FBI agent and asked young Brown about the Thursday night goings-on in apartment 14B, the Glover place.

The agent made specific reference to a tall, light-skinned man in the area at the time of the weekly meetings. Although his mother had attended the first meeting, young Brown had little to offer. The youngster viewed the agent with no particular alarm or animosity; in fact, he was a fan of the radio drama The FBI, in Peace and War. This popular show promoted a positive image of J. Edgar Hoover and the Bureau among Negroes, and it was a valuable tool for the recruitment of his white agents and staff.

During the first few Hartford meetings, Malcolm went light on the Messenger’s tough remedies. In hardscrabble Philadelphia, where moral reform was shamefully lacking, he had clamped down hard. There, a longtime Muslim named Jeremiah X, along with some backsliding practitioners (several of whom had served hard time in prison), had been disciplined by Malcolm to one meal during a workday that began with prayer at dawn. He outlawed cigarettes and alcohol, cold turkey. And Malcolm punctuated the brothers’ habits with the five daily Muslim prayers, arms folded, facing the east, petitioning Allah in gibberish Arabic.

Starting with a blank slate in Hartford, Malcolm saw no reason to throw the fear of Allah too quickly into the hearts of hardworking potential converts. The Yacub myth was kept in storage, for example, as were the teachings about the Mother Ship, which already had clocked several overhead sightings in the sky above the believers down in Philadelphia.

“Never give meat to a baby; always give them milk, and you’ll never lose them,” Malcolm had advised his brother Philbert on his method of recruiting Muslim followers. “That is the KEY in setting up new temples . . . one of the hindrances of the past in trying to propagate Islam, we over-taught the lost-found, giving them meat that they just could not digest, thereby making many rebellious and go back just because once we got them to open their mouths (minds) we started giving them too heavy a food that they could not digest (see) yet.”

Nevertheless, disciplining the faithful in Hartford taxed Malcolm’s patience at the outset. Both Rosalie and her daughter relentlessly smoked, as did others in the apartment. Malcolm initially endured the heavy, carbon-nicotine haze in silence. When offered pork chops, he simply declined. (His famed, upchuck-inspiring lecture on the sins of eating meat from the worm-infested swine would come later.)

Early on, he spared the candidates the full exposure that the advanced believers were subjected to in the Springfield temple. Cigarettes there were already forbidden; pork was banned absolutely as the devil’s meat; and Malcolm had imposed a sedate dress code, and a daily mimicking of Arabic prayers facing east.

Twenty-two-year-old A. C. Williams crawled into the arms of his neighbors. His shirt and trousers were caked with mud; and his body was oozing blood from indistinct portals.Aside from ethical reform and Muslim submission, it was Malcolm’s clarion call for black resistance to racism that pitched him beyond the outer reaches of Elijah Muhammad’s strictly religious orbit. This very sociopolitical message stirred in Mrs. Glover a troubling memory of an encounter with the Ku Klux Klan back home. It was an incident she rarely discussed, even with her closest friends and associates.

Malcolm broke the ice one Thursday evening while discussing the recent news of another such tragedy: the widely publicized lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till on August 28th, 1955. Mrs. Glover broke down sobbing and described to Malcolm the incident that had driven her out of the South more than a dozen years before—and that made her a refugee fleeing her birthright religion of Christianity.

*

On Monday, May 12th, 1941, Rosalie Glover heard gunshots in the distance. Such night sounds were not unusual in the hamlet of Quincy, Florida, where firearms were plentiful and hunting was a sport for some and the means of subsistence for many. The gunfire, however, was followed this evening by plaintive moaning. Neighbors in the wood-frame houses lit by coal oil lamps cracked open their doors. The groans, clearly human, grew louder, attracting a few scouts, who passed along the word that someone had been shot.

Twenty-two-year-old A. C. Williams crawled into the arms of his neighbors. His shirt and trousers were caked with mud; and his body was oozing blood from indistinct portals. Tearfully, Williams said that he had been waylaid and shot; his eyes, wide with horror, said the rest: it was a crosstown attack.

Mrs. Glover kept her children at a distance.

Quincy police had picked up Williams in town a couple of days earlier. The Gadsden County sheriff arrested him on suspicion of attempting to assault a 12-year-old white girl. That evening, a group of four white men stormed into the county jail. It is not clear what transpired between the angry men and jail authorities.

However, they left the building with Williams as their prisoner. Beyond the reach of the dim lights of town, they beat him bloody about the head and body; then they shot Williams several times and left him for dead at the side of the road near a tobacco field.

Somehow Williams survived the battering and the gunshots. Regaining consciousness, he writhed his way homeward, as if by rote. A neighbor of Mrs. Glover allowed the men to bring the severely injured Williams into her home. Innocently, she called the police.

Williams was promptly then rearrested by Gadsden County Sheriff Luten, as a fugitive—although clearly he had been kidnapped out of jail by the white men bent on lynching him. There is no record of the sheriff expressing interest in the men who kidnapped his prisoner. On the advice of a doctor, the sheriff sent the ailing Williams for treatment by ambulance—without guards—to a Tallahassee hospital, about 25 miles away. The sheriff who had allowed the original abduction was quoted in an article in a New York newspaper as saying that he didn’t “anticipate any more trouble.”

En route to the hospital, however, the Negro ambulance driver, a Quincy resident named Will Webb, was forced off the road by “four or five [white] men.” Webb reported, “One of them said they wanted the man and didn’t want any trouble. I told them they wouldn’t get any trouble out of me, because I didn’t even have a pocket knife.” The sweating mob, none too proud of its initial attempt, abducted Williams once again.

Several hours later, the hideously bruised and bullet-riddled body of young A. C. Williams was found on a bridge over a creek five miles north of Quincy. Such vigilante action was not new to the area. Four years earlier, in 1937, two Negroes accused of stabbing a policeman in neighboring Leon County were taken from the county jail by a white mob and lynched.

The tortuous Williams killing bore the unmistakable signature of the Ku Klux Klan. Keeping Southern Negroes “in their place” through just such brutality was the chief mission of these so-called white knights. Systematically, as a teaching point, they would kidnap and torture an available Negro attached to a transgression against a white person; almost any charge, no matter how sketchy and unsubstantiated, would suffice.

The vague “attempt to assault” charge against Williams was typical. The victim would then be ceremoniously tortured, often castrated, sometimes before large crowds in open fields. Sheriffs and police chiefs most often cooperated with the abductors and murderers, rarely detailing a report of the incident. When those in the civil rights movement later persuaded the federal government to press for a trial, which was rare, the all-white jury never failed to acquit the killers. Indeed, the white community was likely to salute them as hometown heroes.

In relating her story to Malcolm, Rosalie Glover said that the incident convinced her that she could not protect her children, especially the boys, anywhere in the South. So common was the lynching of Negroes in the “modern” South that a Washington Post story on January 2nd, 1954, reported the notable good news that for two years running, no one had been lynched in the United States. “End of Lynching” proclaimed the wildly optimistic headline in the Post.

The following year, as if to compensate for the lapse, two white men in Mississippi abducted Emmett Till in the most notorious lynching of the era. The adolescent visiting from Chicago allegedly whistled at a white female clerk, Carolyn Bryant, in a grocery store and, according to his cousin, upon leaving said, “Bye, baby.” The two, including the woman’s husband, abducted and beat the youngster mercilessly, riddled his body with bullets, affixed a 75-pound fan from a cotton gin around his neck with barbed wire, and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River—all for “talking fresh” to a white woman.

The Moorish temple dropout was determined to rekindle the Islamic fires that had been banked by corruption.Following the internationally publicized, open-casket funeral of the victim in Illinois, an all-white Mississippi jury freed Till’s white killers on the strength of the 21-year-old Bryant’s testimony that the teenager had physically grabbed and verbally harassed her. “I was just scared to death,” she said.

Some six decades later, she admitted to a writer that her testimony that Emmett Till had made verbal and physical advances was fabricated. “That part’s not true,” she told Timothy Tyson, author of The Blood of Emmett Till. Whipped along by the Soviets during the Cold War, the outrageous Till verdict was presented to the world as an example of just how racial justice was dispensed in America.

The accused men had publicly maintained that they did not kill Till. Double jeopardy prevented a retrial. So after the trial, the white killers of Emmett Till brazenly sold their story for $4,000 to author William Bradford Huie, explaining in cold-blooded detail exactly how they executed the act of terror. Huie, who wrote best-selling books about other such civil rights atrocities, published the confessions of Till’s acquitted killers in Look magazine.

The determined efforts of Emmett Till’s mother and the timing of the case a year after the Supreme Court had outlawed school segregation rendered the Till lynching a major stimulus for the civil rights movement—and for the rise of young Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. The Southern-based Christian minister would provide the nonviolent alternative to the self-defense posture of the Muslims pushed most aggressively by Malcolm X.

For Mrs. Glover, the 1941 Klan “message” killing in her hometown of Quincy was a threat to be heeded. She immediately loaded her two young sons and three daughters aboard a train and headed north to Connecticut. Four of her older children had already migrated to Hartford or other Northern cities

Despairing of the Holiness Church that had been her “rock of ages” in Florida, Mrs. Glover joined the Hartford branch of the Moorish Science Temple, which promoted a “return to Islam as the only means of redemption.” Emphasizing African heritage, moral uplift, and economic self-help, the local temple was headed by a man named Sheik F. Turner El, who conducted meetings in a small hall over a shop on Albany Avenue. Glover and her husband also took their children to the group’s 275-acre spread in Massachusetts.

Upon discovering that funds raised to pay the mortgage on the Great Barrington retreat were being misdirected, Glover and other followers lost confidence in the leadership. It was then that Mrs. Glover began visiting the Islamic temple, 25 miles away, in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The Moorish temple dropout was determined to rekindle the Islamic fires that had been banked by corruption. Quite beyond the dogma about the Qur’an, such as it was, and the moral uplift, Rosalie Glover was captivated by the raw aggressiveness of the young captain whose message of social resistance was nothing short of a call to arms. She had finally found comfort in the young and apparently fearless Malcolm, a minister who preached self-defense and ignited among Negro listeners a resolve to resist.

The act of lynching had long been a standard motif of the NOI. The image of a rope looped around the neck of a Negro was inscribed on backdrops of Muslim classrooms where ministers instructed students about this historic handiwork of the “blue-eyed devils.” As a recruiting tool, the Muslims never tired of such anecdotes as Mrs. Glover’s recounting of the lynching of A. C. Williams.

Malcolm was masterly at folding such accounts of terror—including the death of his father—into a bill of particulars against all white Americans. And he held that bill out as a score that one day must be settled, if only, as the Messenger instructed, by Allah Himself.

As in earlier days, this model city of Hartford became in the 1950s something of an oasis for Southern Negroes seeking jobs and a better life. The economy continued to boom, and Connecticut had just elected as governor a liberal Democrat, Abraham Ribicoff, the state’s first Jewish chief executive, who was popular among blacks.

As with most challenges, Malcolm was quick to grasp the unique significance of the Hartford experiment. The primal drive of the son to surpass the father also drives the protégé to surpass his mentor—and thus to please him. Conversations with relatives and with longtime associate Captain Joseph suggest that Malcolm viewed Hartford as a defining chance to build a temple from the ground up—and thus secure his special place as an organizer and leader.

Away from the intense rivalries, the police pressure, and the press coverage in cities such as New York and Philadelphia, the creation of the Hartford temple became a case study of Malcolm’s signature technique and his impact as a young minister spreading his wings.

The recruits whom Malcolm was nursing to salvation became too numerous for Rosalie Glover’s cramped apartment. So the Muslim operation was moved to the home of her oldest daughter, Alzea. Alzea and her husband, Eddie St. John, had a roomy duplex, at 40 Pliny Street. The Thursday sessions featured Malcolm’s stepped-up lectures on black unity and self-respect.

He illustrated his points about how every other people in the United States—save the Negro—had developed businesses, jobs, and self-reliance. Robbed of their African names and mother languages, the “so-called Negroes” were yet begging their white enemies for jobs, education, and housing. The housing issue got traction among the nodding heads in the modest living room of the St. Johns.

As in most Northern cities fielding black migrants, housing remained a pernicious obstacle in the 1950s. Suburban tracts constructed on a vast scale for soldiers returning from World War II—and backed by Federal Housing Administration (FHA) grants—were generally closed to Negro veterans.

“Restrictive covenants” limited ownership to whites only, including recent immigrants from Europe. In developments like the 17,000 tract houses of Levittown, built on Long Island between 1947 and 1951, federally subsidized housing generated equity wealth and spawned a new generation of white middle-class Americans.

Shut out of Levittown—the prototype for postwar suburbia—and other such developments for decades, Negro veterans were belatedly granted lesser subsidies for scatter-site housing in generally depressed areas. Moreover, the government subsidized public housing for Negroes that were not owner-occupied—like the homes for whites in suburbia—but rented to low-income families in inner-city areas.

Malcolm related Hartford’s housing bias to his parents’ Midwest experience back in Nebraska, Wisconsin, and Michigan.These federally backed housing projects capped family earning for eligibility at little more than minimum wage. The U.S. government essentially ran a two-tier program, encouraging a permanent Negro underclass of renters while operating the FHA-backed suburban home ownership program to stimulate a dramatic growth of the white middle class.

Bellevue Square, where Malcolm held his initial Hartford meetings, was just such an inner-city housing project. It was subsidized by the federal government for 501 working-class renters, 100 percent of whom were Negro. Citywide, according to the 1950 census, some 90.4 percent of the 12,790 nonwhite residents were crammed into a small pocket of the deteriorating North End. A seven-part series on city housing published in 1956 in the Hartford Courant opened with a blunt admission:

One of Hartford’s largest builders laughed when he was asked whether he would sell any of his new houses to a Negro. He laughed with reason, for the question was a naive one. Negroes cannot purchase any of the builder’s houses, nor would a real estate broker sell an older house to a Negro.

Even should a Negro find himself in fortunate circumstances, after contriving a way to bypass or hurdle the first two barriers, his chances of obtaining conventional financing from Hartford’s lending institutions are mixed . . . discrimination solely on the basis of skin color does exist in the city.

Malcolm knew well that this pattern was nationwide and of long standing, and that it was not lacking in malice and aforethought. He related Hartford’s housing bias to his parents’ Midwest experience back in Nebraska, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

The all-white housing covenant that had prevented Malcolm’s father from legally living on land he purchased in Lansing had, at least legally, been voided by the 1948 Supreme Court decision in the McGhee and Shelley cases. In addition to this national ruling, the Connecticut Civil Rights Commission had recently voted to include the state’s real estate brokers under the fair housing provision of the Federal Housing Administration.

However, Mrs. Glover and other Muslims informed Malcolm about housing discrimination resulting from a new dodge of the local realtors. The code of ethics of the Hartford Real Estate Board, for example, contained a specific, exclusionary provision that read, “A realtor should not be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or use which will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”

That clause was used to restrict Negroes from living in white neighborhoods. Without proof—indeed, the evidence ran counter—prospective black home buyers were preemptively accused of “bringing down property values.”

In the segregated city, where blacks constituted a small minority, they nevertheless grew to become the largest ethnic group in one elementary school and one of the three local high schools. In due course, as in urban areas generally, most Negro children would end up in predominantly black classrooms from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Malcolm, however, did not offer the Pliny Street group a strategy for contesting the practice of the Hartford public schools or the policy of the real estate board. The fight for inclusion was left to the leaders of the local NAACP and the National Urban League.

Changing the behavior of the “blue-eyed devils,” Malcolm observed, following his instructions from Elijah Muhammad, was a nonstarter. Instead, Negroes had first to change their minds about white folk altogether. But most important, Malcolm argued that blacks had to change their minds about one another and about themselves. They alone held the key to their upward mobility, he taught repeatedly.

The white man, he said, is a devil in real estate as in all other earthly matters. “The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us,” Malcolm said, that whites’ insistence upon keeping to themselves, “living among themselves,” at all costs—often brutalizing Negroes—was as much an expression of their evil nature as barking was a part of a dog’s nature.

__________________________________

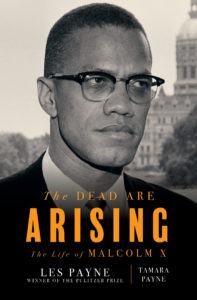

Excerpted from The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by by Les Payne and Tamara Payne. Copyright (c) 2020 by the Estate of Les Payne. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.