What’s In a Literary Brand? David Guterson on Maintaining an Authorial Persona... Or Not

How the Author of Snow Falling on Cedars Remained True to Himself as a Working Writer

My first novel, Snow Falling on Cedars, has Cliffs Notes. Essays about it are free online or can be downloaded for a price. Barnes & Noble sells a Snow Falling on Cedars lesson plan in its Nook Book format. The title is legitimate provender for the television show Jeopardy! and lends itself to crossword puzzles. Snow Falling on Cedars is a movie, too—and finally, my identity. I’m its author, first and foremost, insofar as the world is concerned. If I had a brand, Snow Falling on Cedars would be it.

How do I feel about Snow Falling on Cedars? Like it’s high priest and worst enemy rolled into one, or the way you might feel toward a house you used to live in. I don’t wear it as a hair shirt or fly it as a Lear jet, and it’s not a millstone or an albatross around my neck. It’s out of my control—if it ever was in my control. One thing I do know: it’s not my brand.

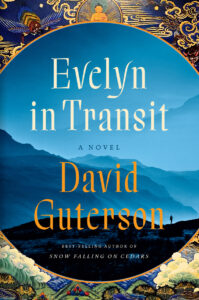

Recently I got a kind letter from a reader of my forthcoming novel Evelyn in Transit that ended this way:

Really loved this one, Dave. And it’s so very different from your other books in terms of language and sentence structure. Almost the opposite of what a person may think of as a Dave Guterson book. Hope it sells like wildfire!

That, of course, was nice to read. It also makes me wonder if there’s such a thing as a “Dave Guterson book.” After all, Snow Falling on Cedars is constituted of dense and mellifluous prose, whereas Evelyn in Transit—to borrow phrasing from its publisher’s marketing language—is a crystalline novel written in a spare, precise style. If the writer of that letter about Evelyn in Transit is right that brand means consistency of language across books, then no, it seems to me, I don’t have one.

By the way, I’m not offended by branding. The main reason I don’t have a brand is because I can’t. I’m not put together that way. Demand a lifelong consistency of syntax and diction and watch me produce nothing. My efforts there would end in vacancy. Boredom would vanquish my attempts to conjure.

The social self is manifold. We’re not someone else while in the throes of enacting our many public personas. On that principle alone, it’s possible to have more than one authentic writing voice. Also, though, it’s easy to posture. Put on the costume, wear the expression, slip on the spectacles, and present yourself as erudite. Make it your goal to publish in the New Yorker and to get there write what you deem a New Yorker story. Enact yourself as one thing or another. As an auto-fictionist or a minimalist—whatever. Project yourself as a representative of a school. Learn a vocabulary, a manner, a worldview. The only problem is, now the page in front of you is poorly written. You can be a lot of things and still be you, but there are a lot of things you can’t be without losing yourself. And it matters, in writing, not to lose yourself.

So there’s that—your many personas, filtered for authenticity—and then, to complicate your branding challenge further, you’re subject, endlessly, to moods.

You can be a lot of things and still be you, but there are a lot of things you can’t be without losing yourself. And it matters, in writing, not to lose yourself.

The plot thickens yet again. Evelyn in Transit is about a young mother in Indiana who one day opens her door on a delegation of robed Tibetans claiming her 5-year-old son is the reincarnation of a Buddhist lama. What does that mean: reincarnation? What, if anything, is incarnated again? I ask as prelude to a related line of inquiry: are you the same person you were twenty years ago? Let me put this another way. I wrote Snow Falling on Cedars in my 20s and 30s. Who was that person? Here’s what I said about him—or me, maybe—in a retrospective I wrote under the title “Snow Falling on Cedars at Twenty”:

That up-and-comer was tight with ambition. His cup ran over with self-belief. He suffered a ferocious surfeit of romanticism. He imagined writing his religious calling, himself a monk. To put all this another way, I had no time for an elevator while doing library research; it was so much faster to bound up stairs. Mania and heroism, in equal measures, spurred me. There I was, too determined to be stopped, indefatigable, filled with the right stuff, and girded by moral striving. In short, I could, and would, save the world, and this I would accomplish by writing things, beginning—in my twenties—with Snow Falling on Cedars.

There are two selves in all of that—one who was, one looking back—and herewith a third, since it’s more than ten years since I wrote that retrospective (which I would not write the same way today, because change is ceaseless).

The reader who wrote to me about Evelyn in Transit saw language and sentence structure as signatures of a writer’s brand. As in Cormac McCarthy, who sounded like himself and no one else at every turn. Someone could prove me wrong about McCarthy by dint of algorithmic investigation, to which I would retort that the need for such backs the point down from always by a telling fraction. Let’s face it—on the multiple-choice test, the Cormac McCarthy question is easy to get right.

For writers like me—less stylistically steady, less given to a consistency of diction and syntax—there’s still a through-line. We might range stylistically, but a sustained vision manifests itself. Snow Falling on Cedars, for all its dense prose, was indeed written by the same person who wrote Evelyn in Transit. The novels, topically, are variations on a theme.

Writing fiction is a lot of things. For me it’s partly music in my head. A pitch develops, a rhythm and timbre, a melody and harmony, a tempo and pulse. Vocals and instrumentation blend anew. If I’m lucky, dynamics deepen. This makes each novel like attending a concert by an artist I’ve never heard of before. It’s wondrous to me, and I’m glad for it.

__________________________________

Evelyn in Transit by David Guterson is available from W.W. Norton & Company.

David Guterson

David Guterson is the author of thirteen books, including the PEN/Faulkner Award winner Snow Falling on Cedars, which was made into a major motion picture, translated into twenty–five languages, and has sold more than 4 million copies worldwide. He lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington.