What’s Good? Raymond Antrobus on Deafness, Poetry and Finding Your Purpose

“Poetry helped me, even if it was just a way to temporarily lift or lighten the narrative of the world.”

I met Thomas when I was visiting a school in Durham in 2017. His teachers whisked me away after I delivered an assembly on poetry to a packed hall of eleven-to-sixteen-year-olds, to sit me in a room with him, a hazel-haired, round-headed eleven-year-old who had two large silver hearing aids in his ears. He kept his head down on the table as his teachers helicoptered over him. Thomas was the only deaf student in the school and the overzealous hearing teachers gathered Thomas and me in a quiet room to meet each other.

“So, Thomas,” said one of the teachers, kneeling beside him. “This is a poet, he wears hearing aids like you.” Another teacher butted in. “Yes, what do you have to say about being deaf, Thomas?”

None of the teachers knew sign; even the fact that sometimes they spoke without facing him showed me that Thomas wasn’t in a room that was accommodating his needs. Thomas kept his head down and finally said, “It’s useless.”

I told Thomas that I felt useless at his age too, that I had internalized this idea that my deafness decreased my value and limited my future (employment and romantic). I explained that I had spent decades pushing against this notion. Deafness is harder when you have to rely on people who aren’t deaf to understand you, people who don’t have the patience to face you when they talk or speak sign, or know when to pause in conversation when there’s a loud noise like an alarm going off or a truck bustling down the street. One of the teachers, perhaps feeling accused and that my words were negative, interrupted again. “Yes, but look at him, Thomas, he’s now a famous poet.” Thomas lifted his head from the table, stared at me, thinking, then asked, “Are poets useful?”

I was the boy who didn’t want to look like the enemy of any system, even a system that hated me, and I know I succeeded despite the system.

“Well,” I said, “that’s a good question, and intelligent people ask good questions.” Thomas fidgeted with his thumbs. “I think there is a power in finding ways to articulate your unique self in the world, a useful power.”

Poetry helped me, even if it was just a way to temporarily lift or lighten the narrative of the world, even if it didn’t always transform my truths and traumas. At times it stopped me spiraling into the story of being that boy who stood low in rank along a long line of other boys who I thought were more clever, more beautiful, more rich, more worthy. I was the boy who wanted to blend in; blending in looked easier, calmer. I was the boy who didn’t want to look like the enemy of any system, even a system that hated me, and I know I succeeded despite the system.

I thought of Thomas when I began doing readings of my first children’s picture book, Can Bears Ski?, a story based on my own experience growing up deaf with hearing parents who struggled to guide me through the hearing world. Part of the purpose of the story is to show deafness as an experience rather than a trauma. During those first readings I got a range of questions from deaf young readers. Some engaged with the story, asking, “Why does the moon have a face?” and, “Can the bears sign?” And there were young readers looking at the other faces on the Zoom call and asking, “How many people here have cochlear implants?” Another question was, “Does anyone here have red hearing aids?” but a common question I received was, “What’s good about being deaf?” There is an innocence to this question, but there’s also a self-consciousness, one that some would say ought to not exist for children so young, but, alas, from birth we’re lucky to be born in a room that isn’t ableist, let alone a world.

Forgive me, I’m not trying to be grandiose; I didn’t mean for poetry to give me a platform for sweeping statements of self-affirmation. For a long time, my poetry was private, it helped me hide. I hid behind poetic thought, in part because it was an intellectual activity that asserted my potential usefulness. In reality, I had no idea what a deaf racially ambiguous boy could offer the “real” world.

*

The poet Deanna Rodger invited me to an event that combined human rights and immigration lawyers with writers and poets responding to the Brexit referendum results. The whole country seemed stunned. At least that was the temperature in London. “What the fuck has he done, what the fuck has he done?” said a voice somewhere, perhaps in my head or from the open windows of the Hackney houses I walked by on my way to a gig at the Stuart Hall Library in Shoreditch. I sat at the front, nearest one of the speakers, as Deanna performed her “London” poem. I performed my “Jamaican British” poem and afterward, as the crowd trickled out of their seats, Deanna and I stood by the exit, greeting and giving farewells to people as they left, not unlike how my grandparents ended their church services, standing by the door, thanking the congregation for attending.

A tall, light-skinned black woman with light brown curly hair and wide intelligent eyes approached Deanna. “I enjoyed your poem, thank you.” She spoke in a somewhere-in-America accent, a clear voice full of gliding vowels; her sounds asserted themselves, projected confidence even as she shuffled away. Noting her American accent, Deanna reached out her arm. “Speak to Raymond, the other poet!” I had recently been in Chicago and was still jet-lagged. Her name was Tabitha. Deanna’s introduction had us exchanging numbers, then dating, then kissing for the first time a week later, outside a bar in Holborn, rain pelting down. I leaned into her lips under an umbrella and months of love and companionship between us followed, made easier by the fact she was having to return to the States, meaning we could be casual and unrestrained. There was something about that dynamic that was liberating.

On early dates I noted that anything I didn’t hear Tabitha say, she repeated without annoyance or exasperation. At a bar or restaurant, she never called across the table or the room, she came to me; she never called up the stairs or through the walls from another room, she came in before speaking. Her deaf awareness was coincidental; it aligned with her style of communication, her love language. She was present, engaged, a good listener.

On an early date, we were in Rudie’s restaurant in Brixton, Tabitha was watching me eat, rushing my food as if in some private and restless race. She reached across the table, touched my hand, asked, “Are you here?” She asked it slowly, so slow it stopped my mouth and I began to taste the scrambled softness of ackee, the peppered brown rice and peas in the candlelight between us.

Tabitha invited me to New Orleans, her hometown, where her large family resides.

The city was almost unwalkable because of the highways and huge willow trees that bulge, pump, and pull up the ground, turning over the paving slabs by the roads that are already punctuated with potholes. It is as if the swampy natural world is pushing back against the concrete one. It’s a city of multiplicity, nothing is one thing. Some of the porches outside the houses waved large New Orleans flags, two red and blue stripes between a larger white stripe with three yellow fleur-de-lis symbols in the middle—it’s a remix of the French flag.

The city is divided into parishes, just like islands in the Caribbean; large bursts of crows often appear in the skies, the Gothic cemeteries full of decaying stone angels that bow over the earth, facing the crumbling walls and the brown and white rusted gates, all of it once underwater, many of the buried bodies washed away somewhere. The twilight zone frequency of the city is easy to romanticize. It’s a city in constant conversation with the dead and undead, never fully recovered from Hurricane Katrina. Tabitha lost family to that terror and was herself displaced. She told me that story and I found my listening change in New Orleans. It’s a city deeply connected to its water; you have to know the nearest bridge over the river to locate yourself and others.

For a long time, my poetry was private, it helped me hide. I hid behind poetic thought, in part because it was an intellectual activity that asserted my potential usefulness.

One night Tabitha took me to Bacchanal, a bar on the bywater near the railway tracks: All the drinks on the tables trembled as the freight trains rumbled past; a wavy-haired man in a purple shirt played the piano in front of us, beside him a bald-headed black man blowing a gold and shiny saxophone, a well-built black man in a black T-shirt on the drums, a white man in glasses and a blue blazer blowing a trumpet, and an afroed brown-skinned man on an upright base—they looked like college students but played like elder jazz musicians. They tapped, plucked, bounced, and weaved through each groove and I forgot where I was until the softer brushes, the spacey trickles, the quick high hats brought me back to the rhythm of the powerful river.

Here, a piano key illustrated my deafness perfectly. All the music disappeared and the pianist had hit a single note. I heard the chord ding, then vibrate for a split second and stop, but it hushed the audience; everyone around me stopped and focused on the band, the vibration of that one note had disappeared, but looking around I could see everyone transfixed, activated in listening. I nudged Tabitha. “You hear that?” She nodded. “What do you hear?” I asked. “The piano key, it’s still traveling.” After a few more seconds I asked, “You still hear it?” “Faintly.” My ears heard the full initial sound of the piano key but almost none of its aftermath, its reverberating resonance. I explained that experience to Tabitha’s cousin Curtis; he smiled, said, “Well, it sounded like the sun setting over the Mississippi River, you should go see it tomorrow”—and the next day I stood on the bank at Algiers Point at 5:45 p.m. and looked toward the bridge, watching the sunset behind it, a sky of bright smoky coal-fire orange and red and pink and blue. I stared, missing none of it.

Later that night, Tabitha told me she loved me for the first time as we lay on the sofa in the living room of the rented purple house that looked out at the river. I didn’t say it back. Not yet. I expected love to feel static, a place you couldn’t move away from, something not second-guessable. But New Orleans was reminding me that there are many ways of holding things, with our ears, eyes, nose, tongue, skin, as well as the things that seem beyond us, like intuition. I was too high to land on any words anyway, too warm with new feelings to name what was stirring me. Everything I was sensing while living beside the Mississippi River was about movement, never arrival.

Two years later, Tabitha and I married by the Mississippi River. After the reception it begins to rain hard. Tabitha said she had an urge to drive to the neighborhood her grandmother, dead seven years, had lived in; she swore the rain had a message in it, swore she heard her grandmother calling, swore she needed to take me to the river to meet her. Tabitha drove downtown and parked and we walked, rain still pelting down. She faced the dark water and I could feel the presence of Tabitha’s grandmother in the rain. I couldn’t see her, but I could; I couldn’t hear her, but I could.

*

Palestinian teacher of the deaf Hashem Ghazal—a leading figure at Atfaluna Society for Deaf Children, an ambassador for Deaf culture and disability justice, often called Gaza’s “Godfather of the Deaf,” and father to nine children (six of them born deaf)—delivered a TedTalk in 2015 entitled “Let the Fingers Do the Talk,” in the Shujaiya neighborhood in Gaza City.

Throughout the presentation, Ghazal details anecdotes from his life, from his father’s passing at a young age, the challenges he faced in his childhood as a deaf youngster, and learning carpentry. He explains how he had to advise his deaf children, to let them know what is good about being deaf; he had to sign to them, saying not to be ashamed of deafness, that “this is a destiny from God, and God has compensated us with the language of speech and sign.” There is a deep need for deaf communities everywhere to have empowering figures like Ghazal, people who understand, through their own experience, how harsh the world can be to the deaf.

In 2024 Ghazal was murdered in an IDF airstrike on Gaza alongside his wife. I had hoped to meet him and make a documentary on his work for the D/deaf, a figure who lived the question and the answer, the good of being D/deaf; someone I could point to for Thomas, for us all.

__________________________________

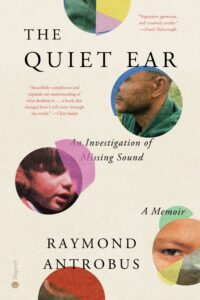

Excerpted from The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus. Copyright © 2025 by Raymond Antrobus. All rights reserved. Available from Hogarth, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Raymond Antrobus

Raymond Antrobus is the author of three collections of poetry, most recently Signs/Music, of which the title poem was published in The New Yorker. His work has won numerous prizes in the UK, where his poems are frequently taught in schools. He is also the author of two children’s books, including Can Bears Ski?, which became the first story broadcast on the BBC entirely in British Sign Language. Antrobus was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and appointed an MBE. He lives in London.