What Writing the Story of a Divorce Taught Me About My Own

Joyce Maynard on Finding Compassion Through the Distance of Fiction

It occurred to me the other day that I’ve been doing the thing I’m doing right now—sitting at my desk, hands on a keyboard, telling a story—for more years than I’ve done just about anything else in my life. Longer than I was my parents’ child, longer than I was married to my children’s father, longer even than I’ve been my children’s mother. It’s not simply what I do, it’s who I am. I was a writer before I married, before I had children, and I have never stopped being one.

Sometimes I write memoir. Sometimes fiction. This month, I’ll publish my tenth novel, and to some readers familiar with my nonfiction writing, the connections between the life I’ve lived and the story of the family in this new novel of mine will bear a certain obvious connection to my own. Sometimes these same people ask me, “how do your children feel about your writing this book?” Well, I love my children as deeply as any parent, but here’s the truth: I do not write to please them. I write to tell the truth.

The story I chose to tell this time around is about a couple—an artist and a writer—who fall in love in the late seventies and raise three children in the country. They make a sweet, good life together in the country, but they lose sight of what they used to love about each other—high on the list, their mutual desire to raise children and make a family, their commitment to being parents.

Their family breaks apart. (They divorce, anyway. I’m not ready to say that a family in which the parents divorce is no longer a family. Just a different kind.)

My children’s father and I were two such people. In love in our twenties. Angry and alienated from each other by our mid-thirties, all memory of what had once been good cancelled out by what got to be terrible. Of all the people for whom this occurrence was painful, maybe it was hardest on our children, who loved us both, and hated what we were doing to each other, as they made their way from one house to the other, Friday nights, and back again, on Sundays, with their brown paper bags full of homework assignments and baseball gloves and stuffed animals and retainers.

I love my children as deeply as any parent, but here’s the truth: I do not write to please them. I write to tell the truth.

Like the parents in my novel, my children’s father and I divorced over thirty years ago. The story I chose to tell in fictional form, this time around, is about five good but flawed individuals. Their New Hampshire farmhouse bears a striking resemblance to the one where our family once made our home. I wanted to explore how each of these characters—characters, mind you, inventions of my imagination—survived the breakup of their family, how that event altered the course of their lives.

But as they tend to, my themes this time around came straight from my life. You could say I know the territory well. Not just the piece of real estate in which the story plays out, but those who made their lives there, including the three who were born on the same bed, under that roof.

Back in the 80’s and 90’s, I used to publish a syndicated column about life in our family. I called it “Domestic Affairs”—and if you read those columns, long ago, some of the things that happen in this new novel of mine might sound familiar. There’s the time the seven-year-old loses the shoe to her new Barbie, and her mother goes more than a little crazy tearing the house apart trying to find it. She simply cannot bear her child’s sorrow. There’s the time, in the first weeks after their separation, when the wife returns to the home of her marriage—where her husband lives now, without her, having fallen in love with someone else—and the two of them silently make love on their old bed, in full recognition of the fact that this will be the last time, ever.

And the time—a year or two down the line—when the wife, hearing from their children about her ex-husband’s plan to sell their children’s picture books at a yard sale, conducts a raid on her old home when he’s away, hauling away bag after bag of books with tears streaming down her face, as if maybe, if she just held onto those books, she might preserve what had already been lost, which was the life they had when their children were little, and everyone climbed into bed together to read Frog and Toad stories, and they believed they’d be together always.

I know this woman. I am her. Or used to be.

Contrary to how it might seem, however, I did not write a memoir about my marriage and divorce and the years that followed. I examined the story of that marriage, that divorce, and the feelings it produced, along with the hard-won lessons I’ve learned over the years since, and I created a work of fiction. From the distance of thirty years, I wanted to look at what happens when two people who once loved each other cease to do so. I wanted to locate compassion for every character in the story of a divorce—every single point of view—in ways I could not have done, when the events in my own life were as raw as a bloody wound. I learned a thing or two, or a thousand, in the decades since my divorce. I wanted to pass it on in the form of this story.

I do not ever offer up advice in what I write. I lay out a story and let my reader come to her own conclusions. The true similarities between my life and my work, this time out, have less to do with Barbie shoes or the rage that leads a woman to smash the buche de noel she just spent hours constructing down the sink. The true part is what divorce does to the people involved. And how, if two people are brave enough, and honest enough, and wise enough, they may surrender their anger and locate a place of loving acceptance.

My novel comes out this week, and when it does I will give a copy to each member of our family. And we are a family, still. The term “broken home” never felt like a description of where we ended up.

I wanted to locate compassion for every character in the story of a divorce—every single point of view—in ways I could not have done, when the events in my own life were as raw as a bloody wound.

It has not bothered me that my children seldom read the books I write. This time, I told the three of them (all well into their thirties now and beyond, in committed partnerships, one with children of his own) that I hope they read this story. I wrote it for all of us. I wrote it for any parent who ever had to sit her children down and deliver the news, “We’re getting a divorce” and any child, of any age, who took in those words long ago and saw her life altered by them forever after.

There is a thing that happens, after a fire burns really bright and hot in a woodstove, where the heat consumes everything, so when you clean out the ashes no trace remains of what fueled the blaze. This is what time and the wisdom of age may provide, for people like myself, for whom the anger and bitterness once seemed inexhaustible.

Then coolness comes. The smoke clears. Even the embers cease to smoulder, and you can look with a clear eye once again—maybe for the first time ever—and say, “we did the best we could.” No relationship that created these children should be seen as a failure. There is no happily-ever-after to any story in which divorce occurs. Somewhere in there, love resided once. Telling the story reminds us. And maybe, once having heard the story, we can lay it to rest.

_____________________________________________

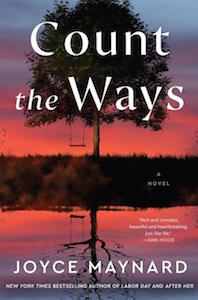

Joyce Maynard’s Count the Ways is available now via William Morrow.

Joyce Maynard

Joyce Maynard is the author of nine previous novels and five books of nonfiction, as well as the syndicated column, “Domestic Affairs.” Her bestselling memoir, At Home in the World, has been translated into sixteen languages. Her novels To Die For and Labor Day were both adapted for film. Her new novel Count the Ways will be published by William Morrow in May, 2021.