What Writers Can Learn From Adapting Their Own Work for the Screen

Sarah Tomlinson on the Slow Yet Satisfying Process of Getting a Book on Film

When I moved to Los Angeles as a journalist and aspiring novelist and screenwriter in 2006, most of the prose writers I befriended seemed a bit suspicious of my TV aspirations. But nearly two decades later, many of those fiction-writing friends are helping to satisfy our culture’s insatiable appetite for marquee television by either working in the writing rooms of original shows or attempting to bring their own books to the screen. The four published authors interviewed here, who have all adapted their own books, share their thoughts on their handicraft, and their war stories of projects that “died in development hell,” as novelist-turned-scriptwriter Benjamin Percy so eloquently puts it on his website.

Almost none of those I interviewed (and almost all who have their work optioned, whether they attempt to adapt it themselves or not) end up seeing their project executed by their original collaborator. Percy, who has published seven novels and the craft book Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction, sold scripts to four different studios, and written for more than half a dozen comics, has worked with several illustrious auteurs, including director Guillermo Arriaga (21 Grams) and producer Tanya Wexler (Hysteria) on two separate film versions of his novel The Wilding, but Percy has yet to see any of his books become TV shows or films.

One of the major questions that accompanies every adaptation is how much the filmed version will depart from the original material.

Sometimes the waiting game that can accompany the development process is actually a blessing. By the time Megan Abbott’s adaptation of her 2012 novel, Dare Me came out, after almost ten years, her edgy and dark tale of competitive cheerleading was more palatable to TV executives. When Abbott first started to pitch the project, originally as a feature film, “the comps were not there, because Hollywood just wasn’t doing anything serious about competition and female athleticism, so explaining the tone was just a constant negotiation,” she says. “But by the time [Dare Me] got greenlit, everything had changed, and Netflix’s Cheer had come out—and the Olympics—so that made it easier to sell and to get it on the air.”

Of course, one of the major questions that accompanies every adaptation is how much the filmed version will depart from the original material. For Tembi Locke this question was complicated even more by the fact she was adapting her 2019 memoir, From Scratch. The book told the bittersweet love story that began when she met her husband, Sicilian sous chef Saro, who was diagnosed with a rare soft-tissue cancer, which he fought until his death in 2012. When writing the book, Locke drew on her experience of storytelling and character honed through two decades as an actress, with appearances on shows from The Fresh Prince of Bel Air to Never Have I Ever.

When it came time to co-create the 2023 Netflix limited series with her sister Attica Locke, an award-winning novelist, TV writer, and producer (Empire, Little Fires Everywhere) one of the first questions was where to launch the story. The first page of the book found Tembi driving a box containing her husband’s ashes home to his family’s Sicilian village. But the show opened with a poignant scene of Amy (Zoe Saldano), the character based on Tembi, holding her husband’s journal.

Because the interiority of the moment had to be implied visually, a journal was a more potent image than a box, especially when the significance of the item was carefully set up, not long into the series, to pay off for the viewer. “Of course, when we got to the adaption…, whereas [in the book] I could languish in, let’s say, the prose of what the character was feeling inside, now all of that has to happen in an action.” Locke says.

These practical concerns can sometimes be jarring for novelists, who have to trade their essentially infinite page count to master film and TV writing. And it’s not just the challenge of representing the interior lives of their characters. “You have an unlimited special effects budget when you’re a novelist,” Percy says. “…But you want your characters to be wandering along, licking an ice cream cone, or something, that’s ten thousand dollars to a hundred thousand dollars, depending on what businesses exist on that street, because you have to shut them all down and pay them their losses for the day. So, the ideal movie takes places in a cinder block bunker with no windows.”

Production costs have an impact on all aspects of screenwriting, including the fact that it would be prohibitively expensive to film a script that is longer than industry standards (one script page equals roughly one minute of screen time). For Abbott, a very precise wordsmith, there is a fascination with how the tyranny of the form’s brevity enforces extreme verbal precision. “I try never to just describe the action because you never want anything in a script to do just one thing,” she says. “You have so little space, so as much as you can convey about that character based on the way they walk—are they walking across the room or are they slinking?—you find a way that it gets in there.”

While some constraints are imposed by the adaptation process, once actors are introduced to the process, they can often convey emotional information to the viewer with a single glance or gesture that it might take a writer pages of exposition to describe. This might mean it’s possible to cut some dialogue or scene setting. On the other hand, the actors themselves may request more information on their characters in order to portray them convincingly.

This was the case when Abbott began working with the cast of Dare Me, which had originally been written from the perspective of one of the cheerleaders, Addy. “Willa Fitzgerald, who played Coach, she wanted to know more about Coach, so she could play her,” Abbott says. “Stuff that I had never known because I had only known what Addy knew about [Coach], we had to kind of fill out. So yeah, the characters do become more well-rounded, and you’re sort of seeing them from more angles, that’s for sure. They become three dimensional.”

The experience of writing across different mediums has clearly given these scribes greater confidence in their ability to serve the stories they most want to tell.

Alissa Nutting, who co-created the adaptation of her darkly humorous 2017 tech satire Made for Love for HBO thought she had already gotten to know her characters intimately while writing the book, but her collaborators in the writing room helped her dig for even greater nuance and dimension. “Writing the book, I was so focused on the way that Hazel was being used by this really powerful voyeur, I didn’t think too much about aspects of privilege, or arrogance, or selfishness, on behalf of the characters,” Nutting says. “So those are all things that came forward, begging the question: if you have this character that’s kind of willing to abandon her father, her friends, her entire life because she is offered this golden ticket, you know, what maybe-less positive personality characteristics are feeding into that, in addition to trauma and pain, and just sort of the structural economics of our society we’re in?”

Nutting, who preceded her adaptation work with extensive experience writing original screenplays, which she began doing to supplement her work as a fiction writer (Unclean Jobs for Women, Tampa) and fiction professor, has been so struck by the collective nature of TV writing that she sees it as a new calling. The amount of solitary time spent as a writer was “one of the aspects of being a novelist that was so difficult, as someone who sort of tends toward the depressive, introverted end of the spectrum,” Nutting says.

Locke recently announced that she’ll once again team up with her sister Attica to adapt the latter’s novel, Bluebird, Bluebird, for Universal Television. Both Percy and Abbott are also pursuing new adaptation projects. But they continue to generate ideas that are meant to be novels first. For Percy this is in part a practical concern. He has found that taking the time to publish all of his ideas as original IP (intellectual property) before trying to adapt them makes others take the stories more seriously, while he himself is less precious about them. In turn, his prose has been positively impacted by his scriptwriting experience. “If you look at my last three novels, they’re fairly slim, and this has everything to do with me learning to be a more efficient writer, as a result of my experience in screenwriting and comics,” Percy says.

Adaptation isn’t just useful for honing a writer’s craft, either. Overall, the experience of writing across different mediums has clearly given these scribes greater confidence in their ability to serve the stories they most want to tell, even if it sometimes takes several attempts to bring a venture to fruition, and it may not be in the form they first intended. Through the adaptation process, all of the writers interviewed seem to have become quite at ease moving between multiple projects—with a well-earned if cautious optimism—that one of their many ideas will eventually take off. In a post-Covid election year, when it can feel tricky to predict what narratives the public will care about, or have the attention span to absorb, it’s affirming to find writers who are staying busy—and employed—while remaining creatively fulfilled.

__________________________________

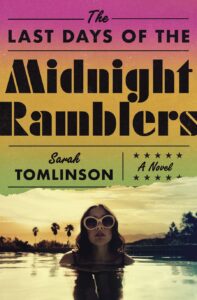

The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers by Sarah Tomlinson is available from Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Sarah Tomlinson

Sarah Tomlinson, a former music journalist, has been a ghostwriter since 2008, penning more than 20 books, including five New York Times bestsellers. In 2015, she published the father-daughter memoir, Good Girl (Gallery Books). She wrote The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers, her first novel, in-between assignments for a who’s who of celebrity clients.