Gloriously Grotesque: How the Cherry Sisters Personified “So Bad It’s Good”

Therese Oneill on the Overlooked Value of Being Your Carefree, Cringeworthy Self

How terrible could they really be,

if people paid thousands to have a look-see?Article continues after advertisement

At 10 p.m. on a chill night in November of 1896, the audience in New York City’s Olympia Theater waited with high expectations.

They had come to see the Worst Vaudeville Act in the World: The Cherry Sisters. An act consisting of songs, costumes, poetry readings, a morality play with gypsies, and, they hoped, an astounding disregard for personal dignity or performative skill. They were not disappointed.

Under the headline “Four Freaks from Iowa,” the New York Times described their act thus:

Three lank figures and one short and thick walked awkwardly to the centre of the stage. They were all dressed in shapeless red gowns, made by themselves almost surely, and the fat sister carried a bass drum. They stood quietly for a moment…. Then they began to sing, in thin strained soprano, and their song was of all the songs in the world…“Ta Ra rah boo de aye.” People listened in amazement as one senseless verse followed another, accompanied at rare intervals by a graceless gesture and intermittent thumps on the big drum.

They then trundled off for a quick costume change. Addie needed a mustache and Effie a handkerchief to put on her head to perform their morality tale, written by Effie herself, “The Gypsy’s Warning.” (The plot of the skit is contained entirely within the title. There was a gypsy. Who warned.) The review continued: “The three sad, flat-chested sisters went through some dialogues which they thought to be dramatic. The words were borrowed from cheap story-papers, and the action from the poverty-stricken imagination of minds worn bare and hard by rough work done on meagre fare.”

They wanted to be part of the fun, even if the only way to be included was to be the butt of the joke.The reviewer said they were grotesque, but not grotesque enough to be interesting. He concluded, “It is sincerely hoped that nothing like them will ever be seen again.”

That reviewer did not have his finger on the pulse of the vaudeville-viewing public. The fellow had just seen an early performance of what would become one of the top-grossing acts at the turn of the twentieth century. Their breasts might have been flat, but their commercial appeal was lusty, full, and heaving.

It was a sibling affair. Though that reviewer got the rare pleasure of viewing four Cherry Sisters, the act was usually just three—Addie, Effie, and Jessie. Back home on the farm in Iowa were two more sisters, and the sisters’ whole act existed only because of one lost brother. He’d lit out for Chicago after their parents died, never to be heard from again. All five of his sisters put on a concert to raise money to try to find him, and they raised $100. That was a small fortune for the time and place! (The time being their pitiable hour of need and the place being the generous hearts of their small-town neighbors.)

Effie, Lizzie, and Addie attempt a comeback in 1929 with “The Gypsy’s Warning.”

Effie, Lizzie, and Addie attempt a comeback in 1929 with “The Gypsy’s Warning.”

The young women had basically carried out a successful 1890s GoFundMe campaign, but that wasn’t how they saw it. They’d packed the house! They’d entertained! They had an act! They promptly rented a bigger hall in a bigger town.

Thus began the Great Cherry Sisters Debate.

The question is not: Were they bad? Because they were. Unequivocally. Terrible. Stank like whale carcass. Rather, the world still wonders: Did they know they were bad?

The review of their next performance, in the Cedar Rapids Gazette, was already puzzling over the question: “they surely could not realize last night that they were making such fools of themselves. If some indefinable instinct of modesty could not have warned them that they were acting the part of monkeys, it does seem like the overshoes thrown at them would have conveyed the idea.”

Were they actually brilliant, playing audiences for the fools in an absurdist performance art, where the joke is You paid money and actually sat through this torment? Or, were they so dim and stubborn that they truly believed they were good?

If Effie’s old gypsy lady could have broken the fourth wall, perhaps she’d have told us in a spooky voice that the answer lies in what the Cherry Sisters did offstage.

Top Billing in 1900 San Francisco. And look! A cakewalk!

Top Billing in 1900 San Francisco. And look! A cakewalk!

It was the same stuff they did while onstage, providing a rough but telling psychological profile.

Take the Gazette review. The Cherry Sisters said that it was some straight-up libelous malarkey. Malarkey! They went to the Gazette office and demanded a retraction. They filed a libel suit against the editor, Fred P. Davis. It was reported he’d been arrested! For the crime of being a big jerk!

But…then the Cherry Sisters agreed with the Gazette to hold the trial at the local theater, where Davis was sentenced to propose marriage to one of the sisters. Which means there was no actual trial, but there was a great deal of fuss and entertainment. Suggesting that, more than justice for their indignities, the Cherry Sisters wanted attention. They wanted to be part of the fun, even if the only way to be included was to be the butt of the joke.

Enforcing this theory, the Gazette eventually printed a retraction, but insisted the sisters write it themselves. Which they did, without use of dignity, dictionary, or the proofreading skills of a third grader—all of which were readily available.

The Cherry Sisters Concert that appeared in the Gazette the other evening was initily a mistake and we take it back. The young ladies were refined and modist in every respict And their intertanement was as good as any that has been given in the city by home people.

The Cherry Sisters filed a lot of frivolous lawsuits during their lifetimes, a habit associated with the attention-starved. Usually for small offenses: a thug took their money from a theatre manager before they could get it, Effie’s finger got smashed in the door when she was trying to shove a rude man out—things like that.

Their biggest court case was when they sued a nasty fellow who was doing pieces for Iowa’s Odebolt Chronicle. He had written: “Their long skinny arms equipped with talons at the extremities, swung mechanically, and soon were waved frantically at the suffering audience. Their mouths opened like caverns, and sounds like the wailing of damned souls issued therefrom.”

Skinny? Skinny? Oh, those were fightin’ words for farm girls in the 1890s.

If their suit against Mr. Davis had been a farce, the defamation suit against the Odebolt Chronicle was for real. It went clear to the Iowa Supreme Court, which ruled that newspapers have the right to freely criticize public performances, even in a downright rude and ungentlemanly fashion.

Between all these lawsuits, the Cherry Sisters kept getting booked at vaudeville venues in small towns. They performed the same act for the unruly audiences, and they kept getting “cigars, cigarettes, rubbers” thrown at them. (Back then, “rubbers” meant “rainboots.” I hope. I sincerely hope.)

And they kept getting paid by sold-out audiences.

In interviews, they answered that ever-present question. They said, “We are not bad.” They explained that the claim they often performed behind a chicken-wire cage to protect themselves again projectiles was pure media nonsense. Nasty reviewers didn’t bother to mention the sisters’ thousands of entertained fans. If things got thrown, it was usually only by two or three ruffians. And that time Jessie ran on stage brandishing a gun, in front of 200 witnesses, and got pelted with turnips—that never even happened! That’s some more malarkey right there, and they’d sue you but good for that if the State Supreme Court hadn’t already said they couldn’t.

The sisters mostly retired their act after Jessie died in 1903 from typhus. Effie and Addie performed sporadically over the next couple of decades. Sometimes their sister Lizzie filled in, but they never tainted their classic routine with any major updates or improvements. People still came, but fewer now; the ferocious vibe of experiencing something outrageous had cooled. It just wasn’t as much fun to throw vegetables at middle-aged aunties.

Their lack of dignity wasn’t in being in vaudeville and in getting harassed; it was that uncomfortable fact that they sought negative attention and liked it.Offstage, the Cherry Sisters still wanted to be noticed, even if it was with disdain. Effie had two (failed) runs for mayor of Cedar Rapids.

Addie and Effie still gloriously grotesque in their golden years.

Addie and Effie still gloriously grotesque in their golden years.

American journalist and historian Jack El-Hai, in his essay “Shaming the Cherry Sisters,” points out that Effie’s campaign was designed to annoy. “[Effie] laid out her platform, which included such unpopular initiatives as a 9 p.m. winter curfew for adults, closing public parks to eliminate them as trysting spots for the young, requiring swimmers to use more modest bathing suits, and the outlawing of profanity on the street.” El-Hai notes the parallel: “It was the old formula of annoying the public in exchange for their attention.

After the vaudeville, the revival, the lawsuits, and the goofball politics were exhausted, the Cherry Sisters finally ran out of ways to perform. They faded away. Having no money left from their years of successful anti-popularity, they spent their old age in the state’s care. Between 1933 and 1944, all the remaining Cherry Sisters died.

Did they know they were bad? Of course. And they knew being bad was good. That’s no different from a literal million young people acting outrageously on their social media accounts for “likes.”

The unladylike thing about the Cherry Sisters wasn’t their off-key singing or stubborn egos. It’s that they didn’t care the attention they were getting was negative. Their lack of dignity wasn’t in being in vaudeville and in getting harassed; it was that uncomfortable fact that they sought negative attention and liked it. Don’t pity them; that would be insulting a conscious choice. Because the turnips were coming at these impoverished farm girls, one way or another.

The Cherry Sisters took control of how they arrived; they preferred to take those turnips hurled onto a stage instead of breaking their backs to squat down and pull them, with their own hands, from the frozen earth. That sort of agency deserves a round of applause.

__________________________________

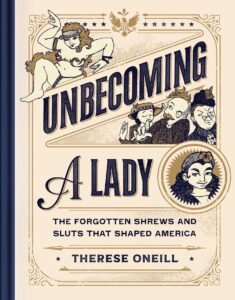

Excerpted from Unbecoming a Lady: The Forgotten Sluts and Shrews Who Shaped America by Therese Oneill. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of Simon Element, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.