What We Learn About Ourselves in the Wilderness

Andrew J. Graff on Becoming a Guide on One of America’s Most Dangerous Rivers

Every raft guide has a rapid that haunts them. The rapid that haunts me is called Lost Paddle, on the Gauley River in West Virginia. It’s a class five rapid over a quarter mile long with dangerous sieves and drops and undercut boulders throughout, each hazard bisecting the current again and again in maze of choose-your-own misadventure.

Simply entering Lost Paddle is tricky, finessing the raft through a rock garden up top while the river rumbles and growls downstream. The spirit of any pre-run briefing for Lost Paddle is basically this, spoken in the calm pool upstream of the chaos—do not fall out of the boat in this next rapid. Just don’t. Not here. I’ve guided rafts for nearly twenty seasons, and whitewater rivers have become a metaphor for my life, teaching me how to be a husband, a dad, an English professor. Lost Paddle, specifically, is an exercise in trying to stay brave.

In 2017, I took a teaching job in southern Ohio, and in my summer off began training in to guide rafts on the New River. To “check out” on the New—to become a certified guide—takes about a month of training that covers swift water rescue and boat handling and miles and miles of thundering whitewater. While I had about a decade of guiding under my belt on smaller rivers, this was my first attempt at a class-five on the bellowing New River with its house sized boulders and waves and drops. Our guide-trainers were all checked-out on the storied Gauley River, a world famous run that made the New River appear tame. These Gauley Guides were revered. Some had great grey beards or long grey braids. While I and the other New River rookies were humbled, our our nerves and skills pressed to their middling limits, the Gauley Guides bobbed down the New River on the sterns of their rafts as calmly as people relaxing on park benches.

Whitewater rivers have become a metaphor for my life, teaching me how to be a husband, a dad, an English professor.

The Gauley, to me and my skillset, was off limits. The New River was already more than I could handle—plenty for a dad in his mid-thirties—and I was proud and content for several seasons guiding it, learning it at its different levels, its milky water racing through the heart of the mountains, me and my wooden canoe paddle named Sappy. I told myself I didn’t even need or want to become a Gauley Guide. Not now, I told myself, when I’d see a group of them strapping down a trailer of rafts bound for the Gauley’s headwater beneath the Summersville Dam.

*

“I’d like to try,” I said to my river manager, six years later, during a bus ride up the mountain switchbacks. “If you could make use of me, and if you think I’m ready, I’d like to try out on the Gauley.”

I’d just come off a thee year hiatus. My wife and I had welcomed another child. The pandemic happened. Life became too busy with bills and block-towers and masked teaching to guide boats in West Virginia. My wooden paddle collected cobwebs in the corner of my garden shed, where I’d pick it up from time to time, after a mow, and take a silent J-stroke in the landlocked Ohio heat. When our kids were out of diapers and guiding again became a possibility, I took it. And that first season back had me wanting more. I felt older and calmer, and hungrier too. I started my Gauley River training two weeks later.

My back was so overworked after my first full day on the Gauley, it twitched during the night in my bunk, paddling on its own while my hamstrings cramped. I had to guzzle protein shakes after Gauley trips. I took fish oil, creatine, dad vitamins. I set up shore lunches for guests next to Sweets Falls. I shivered in the October rain when it fell through the fog. I lost a toenail in a rapid named Iron Ring. I’d sleep like a bear, then drive back to Ohio, where on Monday morning I’d plot out another chapter of Peter Heller’s novel, The River, on the blackboard in my lit course called Wilderness Writers.

“What are these characters finding out about themselves in the Wilderness?” I’d ask the class. And what was I finding out in the wilderness? What were my kids finding, as their dad repeatedly packed his duffles and came home sunburned and filled with stories about flips and swims and waterfalls.

“Daddy is doing a scary thing,” I told my young daughter. “But I really want to do it too. Daddy is trying to be brave.” What I didn’t tell my kids is that the Gauley had already claimed two lives during the first two weeks of its season, a bad flip in Iron Ring and an undercut rock in a rapid called Shipwreck.

“Which one’s you, Daddy?” my kids would ask when I showed them pictures of a raft charging the lip of Sweet’s Falls, a fourteen foot drop.

“The one guiding,” I’d say, this brave sort of pride rising up in me. “The one in the red helmet.”

There were lessons in the value of humility too. I got to tell my kids about the time I got spanked by a rapid called Wood’s Ferry. In Wood’s Ferry, a class-four, you have to drive the raft river left. I got swept river right, and then couldn’t make the ferry. There’s a big boulder on the right with a ledge called The Juicer. My raft got juiced. And in the hectic aftermath of dumping everyone except for me and my trainer, while two trips of raft guides floated and gawked from downstream, my raft planted itself on a sloping rock. I fell out, backwards, landed on the rock like a turtle on its back, and then slid in slow-motion, flailing, head first into the water. I was reminded, before I was even fully submerged, to never take the Gauley for granted, especially as my confidence out there increased.

*

The morning of my evaluation run went okay. No flips, no big disasters, but I ran half of the first class-five backwards, bellowing paddle commands like a frightened dog—Forward! Stop! Left side Back! All back! Barrruuf! Lost Paddle was harried. I ran Sweets Falls a bit on the steep side. On the bus ride back up the mountain, debriefing with my river manager in a back seat, I could tell he would have preferred cleaner lines. I still had the afternoon run down the Upper to prove myself. This was it.

I was reminded, before I was even fully submerged, to never take the Gauley for granted.

As my raft drifted into Lost Paddle that afternoon, I exhaled a very deep breath.

The river manager chuckled quietly where he sat next to me in the back. “I know that sigh,” he said, and then, “You got this.”

I’d aced the other rapids that afternoon. Lost Paddle was the last one that truly worried me.

“Forward!” I yelled, building momentum toward the rapid’s first drop, driving out toward the river’s center before turning the bow downstream to the left. The crew drove hard with their paddles. I barked loud. As we reached the river’s center, it was time. I looked downstream, braced Sappy against the raft, twisted the paddle blade vertical, and began to pry left, pumping the paddle hard against the water.

The bow turned, but I needed more angle. I pried harder, leaning into it.

“Left back!” I yelled, shifting the crew for two strokes to help rotate more quickly. “Now forward!”

I’d found my angle in the fast current, the fourteen foot raft bucking just right through the waves on its left bow. I strained to hold my pry in the water. And that’s when Sappy’s shaft began to crack.

I heard it. Amidst the whitewater droplets suspended in air, and the bright sun, and the green raft racing into the longest and most difficult rapid, on my check-out run on my Everest river—I listened while Sappy’s shaft began to stress fracture. Pop. Snap. I didn’t dare let go of my pry stroke, or we’d zip across the current and set off a chain of bad consequences. So I kept the pressure on. Pop. Crackle.

I remember a very clear thought. Oh no, Sappy! Not now!

And Sappy didn’t. Sappy held, and we made it through Lost Paddle. Frankly, we nailed it. We sailed past Shipwreck too, and down the smooth tongue of Sweets Falls. My paddle wouldn’t make the snapping sound as long as I took it easy on my pry strokes. A close inspection in calm water showed stress fractures along Sappy’s laminate. The layers of wood in its shaft, fibers that have borne the flex of over eight hundred runs down years of rivers, began to literally pull apart. Sappy was a battle horse that made the highest hill and broke itself doing so. It would never guide a river again.

That afternoon—late in the day when the sun began to slip behind them again—I drifted with my boatload of guests and river manager toward the take-out. My muscles were exhausted. I was hungry. My paddle was broken. And I was proud. I and Sappy had left it all on the river. We’d been brave.

Then my manager made an announcement to the raft. “Not everyone can guide this,” he said. “The Upper Gauley is one of the hardest rivers to guide. If you can guide here, you can go anywhere in the world and guide there too. Today was Andy’s check out run.” Then he grinned. “And as of right now, Andy here is a fully checked out Gauley Guide.”

“Yeah?” I said, beaming, giving Sappy’s T-grip a hard squeeze.

“Yeah, man,” he said, and the crew cheered, and then my manager gave me what may have been the most satisfying a fist bump I’ve ever received. I thanked everybody. We got phones out of dry boxes and took pictures—I wanted to capture the moment for my kids, and for myself—and then I paddled a few final and gentle J-strokes with Sappy to the gravel take-out, slid off into waist deep water, and pulled the raft ashore.

__________________________________

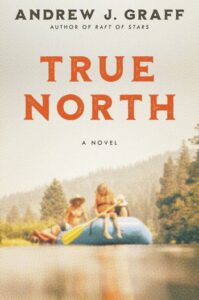

True North by Andrew J. Graff is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Andrew J. Graff

Andrew J. Graff is the author of novel Raft of Stars. His fiction and essays have appeared in Image and Dappled Things. Andrew grew up fishing, hiking, and hunting in Wisconsin's Northwoods. After a tour of duty in Afghanistan, he earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop. He lives in Ohio and teaches at Wittenberg University.