What to Read While You’re Recovering from Top Surgery

These Books Arrived Exactly When I Needed Them

This essay mentions suicidal thoughts and a method of suicide.

A week or so after my top surgery, I went to the disability insurance office in San Francisco, an hour and a half away from my East Bay home by public transit. You should be in bed, said my housemate. She was right, but I needed my check, and I didn’t want to ask any friends to take the day off to drive me. $100 for a Lyft was out of the question. I was feeling okay, I thought. And really, was I supposed to stay horizontal forever?

The walk to the station was okay, and the sun felt nice. Even when the train shrieked to a stop and gulped open, bodies packed inside, and I realized that I couldn’t lift my arms to hold onto the loops overhead, let alone support my weight by leaning against the side of the car, I didn’t panic. Maybe someone would see the aura of the Recently Operated Upon surrounding me and offer up their seat. When I’m not recovering from surgery, I do the same, standing up so certain passengers—Chinese grandmas with translucent visors, people with protective palms on distended bellies, mothers of children old enough to walk, but only just—can sit down. But I don’t look like someone you would give your seat to. My aura must have been too weak.

When the train lurched into motion, I planted my feet and braced myself, collapsing against other bodies when I lost my balance, all the time hunching protectively over my chest, where everything was still as raw and pink as sashimi. What if someone had run into you? asked a friend when I later told her of my BART adventure. The answer hit her before I could reply, her face blanching, her mouth twisting into a grimace. She was imagining an elbow making surprise contact with the still-knitting tissue congealing over my ribs.

At least my visit to the disability office was a success. When you’re trans, you have to work ten times as hard to prove you are who you say you are, but my in-person appearance seemed to appease the cis gods of bureaucracy; my check, I was told, would probably be forthcoming. The next day, I discovered that a stitch around my right areola had come loose on my journey, laying out the future shape of an uneven scar. I tried to console myself with the knowledge that I’d only left my bed because I had to.

But the stitch was a reminder, one even more potent than getting cut open, that I was no longer one single piece of person. Post-surgery, I was live meat on the mend. I pictured a petri dish with electrodes suctioned onto it; Christ’s sliced side; a monster undergoing slo-mo soldering via scar tissue and iridescent bruises. I wanted nothing more than to move, but every time I tried, my body caught up with me, sending me back to bed in a combination of fatigue and smothering depression.

I’ve never been good at sitting still, but while I recovered, I had to.The window of time between deciding to have my breasts removed and my day trip to the operating room was six months. In the world of transsexual surgeries, this is remarkably, miraculously, perhaps ill-advisedly short. I’ve never been good at sitting still, but while I recovered, I had to. It’s just hurry up and wait, as someone wrote on one of the hundreds of top surgery forums I scrolled through from my bed. Before going under the knife, I was confident that I could easily do nothing for a month or two. I’m basically going on vacation, I joked when I told people about it. I predicted, with the confidence and stupidity of a person who’d never had surgery before, that compared with decades of numbing dysphoria, recovery would be easy as pie.

I was wrong. The only thing greater than the desperate sadness that settled into my bones was my surprise that, after years of dormancy and the procedure that was supposed to change my life, the urge to kill myself had returned. It was unreasonable, and yet it was there, despite the support of my loved ones, the outpouring of food and flowers and gifts from people who cared about me. These gifts included books, and with the exception of changing my bandages, reading was the only thing I could do besides close the garage door and start up my housemate’s Subaru.

Your nana got depressed after she had her hip replaced, said my mom. It runs in the family.

They’ve just cut through so many nerve endings, it’s even more intense than for other kinds of surgery, said my friend. This is normal.

You haven’t integrated these changes yet, said my therapist. It’s going to take time.

It’s been almost five months, and I’ve integrated the changes, I think—the depression has abated—though I’m still healing. The books helped. Is this because they were good, or because they were tokens of thoughtful care, paperbound time-erasers that arrived exactly when I needed them? I think both are true, which is why, although I recommend all of these, I recommend this even more: When your friend is lost, consider giving them a book.

Jenny Zhang, Sour Heart

(Lenny)

Sour Heart is a short-story collection, but it felt like the world’s most expensive weighted blanket. Even fuzzy from painkillers, I never wanted it to end, and for over 300 pages, it obliged me. It came in a care package from my dearest friends, along with Rx Bars and crystals and handmade pillows to cradle my tender body.

Sour Heart’s eight stories are told by first-generation Chinese-American girls and women. The stories share many similarities, often overlapping in cruelty, beauty, and location (Brooklyn and Long Island and Shanghai), but every storyteller is distinctly wrought; if the collection itself were a music box, the voices would be its gears, autonomic and yet collaborative. Zhang expertly fashions the tragedies of diasporic family life, but I found reassurance in her stories about other humans at war with their own bodies, each bowel movement and poverty-related illness and unaccountable appetite a distinct battlefield. When you feel trapped, the stories of other trapped people don’t make you happier, but they do make you a little less lonely.

Loneliness, Zhang reminds us, is most painful when we experience it while surrounded by those we love. In Our Mothers Before Them, Annie listens as her family praises her mother’s voice, telling and retelling the story of a singing career that could have happened but never did. Now married with two children and living in the United States, Annie’s mother only sings into her karaoke microphone at home. When she learns that her favorite singer, Taiwanese pop star Teresa Teng, has died, she mourns as if for a family member (“Everyone said I looked like I could be her sister,” she says). When she says she wishes she had named Annie after Teresa, Annie’s own name stands in for a greater arc of regret, a loss that she has come to represent, merely by existing.

“I should have gone with my initial impulses. From now on, you’re Teresa. Teresa, my heart, should we get McDonald’s for breakfast tomorrow?”

I didn’t answer because I wasn’t sure if she was calling for out for me or her favorite singer.

“Hello? Are you asleep? Where’d you go, Teresa?”

“Are you talking to me?” I asked.

“I’m talking to Teresa,” she snapped, tears dripping down her cheeks.

David Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz

(Semiotext(e))

My friend Charlotte sent me this book, a collection of the artist’s transcribed audio recordings from 1981, 1982, 1988, and 1989. Ranging from his mid-twenties to the years following his AIDS diagnosis, The Weight of the Earth is as much self-documentation as it is an admixture of dream journaling, art theory, sexual imaginary, and the out-of-body experience of dying from what, at the time, was almost certainly a terminal illness. I read it in bed at all hours of the night, just as Wojnarowicz recorded many of his entries.

In an entry from 1988, the year I was born, Wojnarowicz says, “When people look at you as a walking disease, a walking illness, a vessel of disease and death, they deny the very life that you carry.” When I began telling others about my plans for surgery, many of them—especially other trans people—were happy for me. I had expected that others—especially cis people—would be repulsed and incredulous of this need to change myself, but I was sometimes surprised by who these people turned out to be. The depression that settled on me after surgery felt like an underscoring of their doubts, a confirmation that I was, indeed, a walking disease, and one that had proven resistant even to medical intervention. Were they were denying the life that I carried, or was it that the burden was me?

Because of his activism and the circumstances of his death, a righteous fury surrounds Wojnarowicz’s legacy. But The Weight of the Earth was a reminder that, for me, his most distinctive quality as an artist is his unbridled joy: in his work and in his pleasures, in his friends and lovers, in his defiant hope. “Sometimes I just want to be by myself, and sometimes I love people so much,” he says; and in fact we can love both these things, the other and the self, because these loves are inseparable and symbiotic. There can be no fury if the beloved is not under threat.

Wojnarowicz has the great artist’s knack for feeling like a treasure that’s for you and you alone; my bed felt like the one he’s curled up on in Peter Hujar’s photo, my physical pain like a descendant of his suffering. And if the pain of this other David, a man from a different time and place, could feel so close to me, so very similar, it occurred to me that his joy might also be within reach.

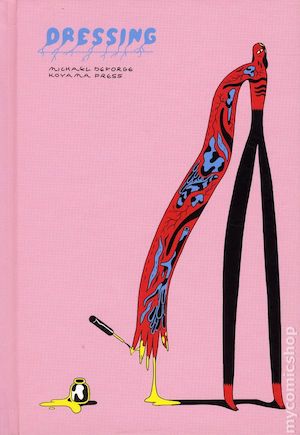

Michael Deforge, Dressing

(Koyama Press)

This book came by way of my friend Avery, who arrived a few days into my recovery on the back of a bike, reminding me that it was summer outside my bedroom. Its funny yet eerie illustrations come with stories, but sometimes the text leeches them of context instead of providing it, making them even stranger than they are at first glance. The colors are various but muted, the lines complex but rudimentary: Noses in bas-relief. Mountain crags cresting hashtag stars. Stick figure people with big eyes and bubble smiles that belie the confusing, creepy feelings behind them.

My favorite story is titled, “Mars Is My Last Hope.” It is about humans colonizing the Red Planet. New arrivals from Earth must wait and see how this alien atmosphere will affect them.

“When will my body change?” a humanoid in a spacesuit wants to know.

“Maybe it won’t,” replies a four-legged friend, whose clothing or body resembles a Klimtian woodcarving. “Some bodies never adapt. In which case, you’ll have to go back.”

“Back to what? Not many cities left to go back to.”

As they transform and lose their language and memories of earth, Deforge’s illustrations squiggle and ooze and run. We feel a calm in the face of inevitability, but that doesn’t make the change any less disorienting or sad.