What to Leave In, What to Leave Out: My Conversations with David Foster Wallace

Adrienne Miller on Literary Life in the 1990s

Feature photo by Steve Rhodes.

When you’re writing a memoir, you find that you’re obliged to confront your own ideas about the nature of memory. In Gore Vidal’s own splendid memoir Palimpsest, he suggests that when we remember an event, we don’t remember it as it actually happened, but rather that we remember our memory of the event. With all due respect to Gore Vidal, whom I love more, probably, than is reasonable, I’m not so sure he’s right about this one. It is true that meaning comes only with time, but it is also true that the past isn’t really the past if you’ve actually been paying attention. Ask yourself: Have I been truly present in my own life? I’ve also always had this sense that time is very permeable. Time, I’ve always felt, is folded up into itself, and into you, and it has never been all that much of an imaginative leap for me to be right back there.

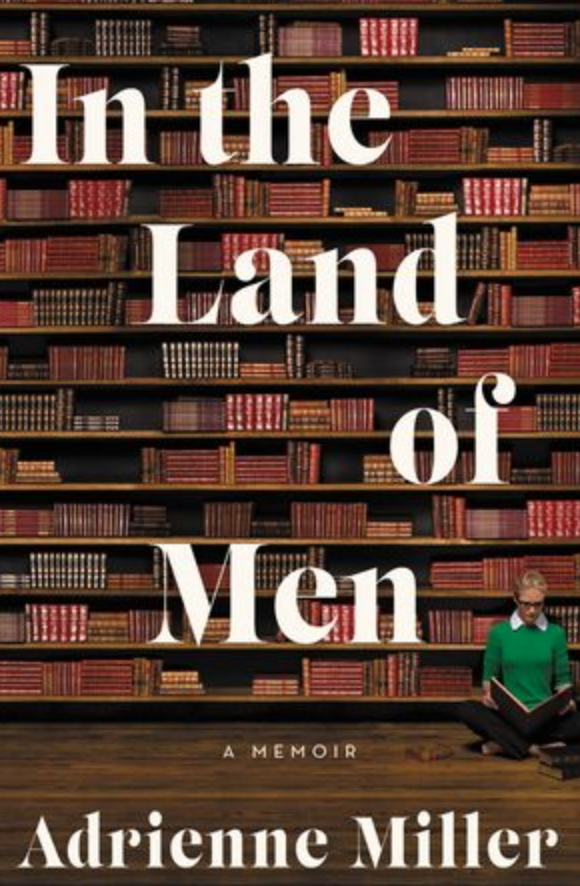

My memoir In the Land of Men is several things: my coming of age in the male-dominated literary world of the 90s, a story for anyone who has ever been the only woman in the room, an elegy to the dying days of the golden age of print, and an account of my relationship with David Foster Wallace. For years after David’s death, I tried to stay away from everything having to do with him. I didn’t want to talk about him, I didn’t want to think about him, and I certainly felt no inclination to ever write about him. I had plenty of other work projects to keep me occupied, I had a busy and happy family life; I’m an optimistic, forward-looking individual, and time-traveling myself back an uneasy past held no appeal.

But a few years ago, I found myself ruminating on some of my early conversations with David, when I was the literary editor of Esquire and he and I were working on edits to his short story “Adult World.” For reasons still unclear to me, I felt compelled to try to get some of these conversations down on paper. As I started working, something eerie happened: I became sort of like Richard Dreyfuss in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, when he gets obsessed with sketching that weird mountain over and over again. But I suppose that’s the only reason to undertake any seemingly impossible, potentially absurd (though hopefully not lethal), project: you’re possessed with a desire to do the thing, and you have no actual idea why.

There are not only about a million different craft decisions to make on each page of a memoir, but there are also about three million different human decisions to make, too.In a practical way, I had some experience training myself in the art of remembering, or at least in the art of remembering uttered speech. When I was a young teenager, I loved reading plays. I had this idea that I wanted to be a stage actor, but I was far too shy (and lazy) to actually audition for anything, so I became one of those tragically nerdy behind-the-scenes theater kids who took a lot of acting classes and got way too obsessed with Stanislavski. For a period in my adolescence I memorized lots of monologues from plays. I believe that my early self-inflicted memorization trials certainly must have helped me develop an ability to recall uttered phrases. I also suppose that from the great playwrights I learned to pay attention to people’s speech patterns and acoustic profiles.

I had a rule when I was writing the book: I would not use reconstructed dialogue anywhere. Ever. Dialogue was to be set in quotation marks only if I believed it was actually said. I’m a real stickler about this. I’m also a stickler about chronology. You can’t go around fiddling with the sequence of events; you’re stuck with what actually happened, in the order it happened.

I found memoir to be a fairly unforgiving form—there’s really not a lot of room in it, and you find out pretty quickly that a lot (or most) of your memories have no place in your story. The truth is that most recollections go nowhere, and if a scene doesn’t function in service to the book’s larger themes, it must be exterminated. It is not pleasant at all for me to contemplate the amount of time I wasted writing scenes I believed had a right to exist simply because I believed they were amusing. The merely funny: not good enough!

There are not only about a million different craft decisions to make on each page of a memoir, but there are also about three million different human decisions to make, too. What to add and what to omit? How, if this is included, might it hurt someone? People, as a general rule, don’t like to be written about. (And people are right about this one.) With fiction, everything is masked, and no one gets damaged (or at least that’s the hope); all decisions are artistic. But with memoir, you’re dealing with actual human beings, it turns out, and you can never let yourself forget that the others in your story are as real as you.

You have to try to be fair to your people. You have to try not to treat any other human being as an object, and you have to try to regard people the way you would hope to be regarded if, God forbid, someone were writing about you. I never imagined I’d write a memoir, mostly because I’m not terribly interested in myself. But I am interested in other people—so that was where I began.

______________________________________

Adrienne Miller’s In the Land of Men is available now from Ecco.